Study: IVF Treatment to Improve Egg Quality May Not Aid Fertility

The success of using mitochondria to ‘reenergize’ eggs is far from proven.

A controversial IVF technique to improve egg quality may not actually increase the odds of pregnancy or live birth, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, in Barcelona, Spain.

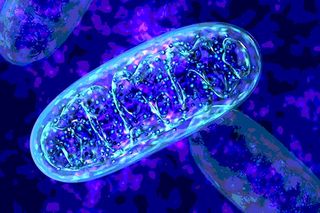

The fertility treatment, known as AUGMENTSM, involves injecting mitochondria from “egg precursor cells” found in ovarian tissue, into a woman’s mature egg along with male sperm. Mitochondria are cellular power plants, processing the energy cells need to survive and thrive. The treatment was developed with the aim of ‘reenergizing’ the eggs of women who struggle to become pregnant via IVF.

Specifically, per its website, the AUGMENTSM “treatment uses the energy-producing mitochondria from your own egg precursor . . . cells, which are immature egg cells found in the protective lining of your ovaries, to supplement the existing mitochondria in your eggs. This process is designed to boost your eggs’ energy levels for embryo development.”

The findings of this small, single-site but randomised trial suggest that this does not happen, with no differences found in live birth rates in either the group that received the IVF treatment to improve egg quality, or the group that did not.

Dr Elena Labarta of the IVI clinic in Valencia, Spain, one of the world’s largest fertility centres and the site of the research, and colleagues followed the outcomes of 59 infertile patients, age 42 or younger, with a history of unsuccessful IVF treatment. The patients were described as “difficult to treat,” and representative of those intended to benefit from a treatment to improve egg quality.

The researchers followed the protocol of the proprietary AUGMENTSM treatment. They found the rate of live birth per ‘reenergized’ and fertilized egg transfer was 41%; among the group that did not receive the mitochondrial treatment for their eggs before fertilization and transfer, the live birth rate per transfer was 39% — a rate too similar to prove the success of the revitalizing treatment.

The “invasive technique” is often a treatment of last resort for couples struggling with fertility even with IVF, says Labarta. “Unfortunately,” she says, “the technique was not found useful for this type of patient, so we see no value for this patient population.”

Previous studies that have shown a benefit to the AUGMENTSM treatment lacked a well-defined control group, Labarta said. “Our study, however, was the first prospective trial with an intra-patient comparison which could evaluate the net impact of the technique in the quality of the eggs, as they all came from the same cohort.”

But Labarta says her research is far from the last word on the success of AUGMENTSM.

“The isolation of egg precursor cells and mitochondrial extraction were processes performed by the external company,” she explained. “Our team could never see the egg precursor cells, but worked with a solution presumably containing the isolated mitochondria from them.”

So while the potential to improve egg quality — even the potential to improve egg quality via mitochondrial therapy — remains, it will require more research before the success of AUGMENTSM and similar IVF treatments to improve egg quality can be fully validated or debunked.

Related

Common, Immune‑Suppressing Miscarriage Treatment ‘No Better Than Placebo’