Suicidal Thoughts Exist on a Spectrum — And Sometimes Involve No Active Plans to Die

In our efforts to save lives, we’ve left a common response to life’s stressors out of discourse: passive suicidal ideation.

The term ‘suicide’ pricks up all ears, and for good reason — the prospect of a loved or known person thinking about ending their life understandably causes concern, or, at the very least, discomfort. But suicidal ideation exists on a spectrum — from passive suicidal ideation, which involves thinking about suicide without any intention to immediately act on it, to active ideation; the latter involves actual, imminent, detailed thoughts and plans to die. In order to respond to the various ways in which people think about suicide, it’s important to tailor responses that befit the intensity of suicidal ideation.

While active suicidal ideation has been given immense attention, and for good reason, passive suicidal ideation often doesn’t get the right kind of help. First, suicide exists in a highly stigmatized space — any mention of it understandably raises concern among, and intervention by, loved ones who want to help, but don’t necessarily know-how. For people who have no plans, this kind of intervention can do more harm than good; it paints passive suicidal ideation as something needing immediate intervention, lest an attempt occurs, which further isolates and stigmatizes people for having thoughts that are a) normal responses to life’s stressors, and b) deserve open and honest conversations.

What is passive suicidal ideation?

“Passive suicidal ideation (also referred to as death ideation) is defined as a wish to die, thinking about one’s own death or that one would be better off dead, in comparison with active suicidal ideation, which refers to thoughts of killing oneself,” according to a study of suicide and suicidal behaviors.

In a personal essay for Outline, Anna Borges writes, “Right now, I don’t actively want to kill myself — I don’t have a plan, I don’t check the majority of the boxes on lists of warning signs of suicide, I have a life I enjoy and I’m curious about the future — but the fact remains, I don’t always feel strongly about being alive and sometimes, on particularly bad days, I truly want to die.” She calls passive suicidal ideation the “gray area between fleeting thought and attempt.”

What are examples of passive suicidal ideation?

In an article for BuzzFeed, Borges sourced people’s experiences and opinions about passive suicidal ideation, uncovering the various ways in which it can manifest. “It can be feeling like you don’t have another way to make the pain stop or hopelessness about the future. It can be indifference about life or the hope that an accident or disease takes the choice out of your hands. It can be about making reckless or self-sabotaging decisions,” she writes.

“The wish to die during sleep, to be killed in an accident, or to develop terminal cancer,” all fall under suicidal ideation, according to a paper published in Current Psychiatry. While these seem harmless, and have been co-opted in social media vernacular through memes and sardonic commentary as a response to life stress, passive suicidal ideation needs to be evaluated closely by professionals, who can determine the risk to life these thoughts actually pose.

What causes suicidal ideation?

Factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, marital and partner relationship status, living arrangements, and social support can determine the likelihood of suicidal ideation, according to a study evaluating the link between depression and suicidal ideation. Psychosocial problems such as “depression, aggressive behavior, anxiety-fearfulness, family discord, personal stress, low self-esteem, and alcohol abuse” have also been linked to suicidal ideation, according to the study. “There is also some evidence to suggest that persons with lower incomes are at higher risk for suicidal thinking.”

Another study evaluating the risk of recurrent suicidal ideation among young adults found that the transition between adolescence and young adult life can be a critical time characterized by “leaving the family home, joining the workforce, attending college or university, engaging in long-term relationships, and starting a new family.” Those predisposed to psychosocial problems, such as depression, can become vulnerable to suicidal ideation while experiencing these life stressors.

Related on The Swaddle:

Teen Suicide Tops Causes of Death in Teens. Here’s Why.

For older people, “disability, depression, and other health conditions as covariates, heart attack, diabetes/high blood sugar, chronic lung disease, arthritis, ulcer, and hip/femoral fractures” can increase their chances of engaging in passive suicidal ideation, according to a study evaluating passive suicidal ideation amongst retirees in Europe. “When grouped by organ systems, conditions affecting the endocrine, respiratory, and musculoskeletal systems were associated with increased odds of passive suicidal ideation.” Researchers explained the increased risk as partially a product of greater levels of disability and depression, which proved to be a detriment to the older participants’ mental health.

How to measure the risk associated with passive suicidal ideation?

The Scale for Suicidal Ideation, or SSI, is a 19-item clinical questionnaire, which quantifies and assesses suicidal intention. The concept encompasses “intensity, pervasiveness, and duration of the individual’s wish to die, the degree to which the wish to die outweighs the wish to live and the degree to which the individual has transformed a “free-floating” wish to die into a concrete formulation or plan to kill him or herself,” according to a report published in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology.

The items also assess the patients’ attitude toward these thoughts, and any initiative they’ve taken to manifest them. Items on the scale consist of three statements that can be rated 0 to 2 by the patient.

One item mentioned “passive suicidal desire,” to which patients can respond with “would take precautions to save life,” “would leave life/death to chance,” “would avoid steps necessary to save or maintain life.” Another measured the effect of deterrents in a person’s life, such as family or religion, that would prevent them from committing suicide, responses to which include “would not attempt because of a deterrent,” “some concern about deterrents,” “minimal or no concern about deterrents.” The scale also evaluated the “sense of capability to carry out attempt,” to which patients can respond with “no courage/too weak/afraid/incompetent,” “unsure of courage, competence,” and “sure of competence, courage.” From 19 such statements and corresponding responses from patients, clinicians assess the kind of thoughts a person is having, where the ideation lies between active and passive, and what kind of help the patient requires.

How and when can passive suicidal ideation turn into active suicidal ideation?

Experts say clinicians tend to regard passive suicidal ideation as low-risk since it doesn’t automatically mean immediate plans to die, which is a faulty approach. “The clinician may feel relieved and not complete suicide risk assessment and prevention. However, passive [suicidal ideation] can become active quickly without warning,” according to a study comparing passive and active suicidal ideation.

The transition from passive to active occurs either due to triggering circumstances or exacerbated mental health issues. “It’s the burdensome-ness of an experience that can become a very big trigger,” Dr. Kamna Chhibber, a practicing psychologist in Mumbai, said. In such a case, “if successively you’re feeling that there are shifts that are happening in mood space, or thought patterns, if there is irritability, you’re feeling less tolerant, there is increased perception of negativity, of things being either too difficult, harder to manage, or feeling ‘I don’t have people around me,’ feeling alone and lonely but you don’t feel connected to people, feeling emotionally your loved ones aren’t doing anything for you — those are all red flags that indicate an exacerbation,” she said, adding “these are shifts that you are observing from your usual way of being — something that is happening that is different from your normal way of being, and these need to be addressed.”

How does one deal with passive suicidal ideation?

Right now, talking about suicide to loved ones, even passive suicidal ideation, is likely to cause panic and grief. As an alternative, experts urge those struggling with suicidal thoughts to reach out to mental health therapists who can better evaluate suicidal intention and risk, and help accordingly.

“People oftentimes don’t give importance to these passive thoughts — until it escalates, and then they are stumped ‘Oh, where did this come from?’,” Dr. Chhibber said, adding that those struggling with persistent, gradually intensifying suicidal ideation should seek professional help.

Related on The Swaddle:

Fear of ‘What Will People Say’ Is Driving Up India’s Suicide Rate

A Canadian study that evaluated young people’s vulnerability to suicidal ideation found only a few participants sought professional help for it. This was possibly due to “perceived stigmatization (i.e., fear of what people think), fear of hospitalization, reluctance to share personal information about mental health problems, not accepting/admitting mental illness, limited access to services, and long waits for mental health services,” according to the study. Instead of seeking help, the study found young participants turned to their social circles to discuss their suicidal ideation — study authors found this especially alarming since peers, or parents, often don’t have the skills to provide help in an adequate and helpful manner, especially for a stigmatized thought process such as suicidal ideation, even if it’s passive.

Therapy, then, might just be the sweet spot where a person passively ideating about suicide can seek help and talk freely about their thoughts, while their loved ones can rest assured they’re getting the help they need. As Borges writes for Outline, we need to create a “middle ground between hypervigilance and complete secrecy.”

Rajvi Desai is The Swaddle's Culture Editor. After graduating from NYU as a Journalism and Politics major, she covered breaking news and politics in New York City, and dabbled in design and entertainment journalism. Back in the homeland, she's interested in tackling beauty, sports, politics and human rights in her gender-focused writing, while also co-managing The Swaddle Team's podcast, Respectfully Disagree.

Related

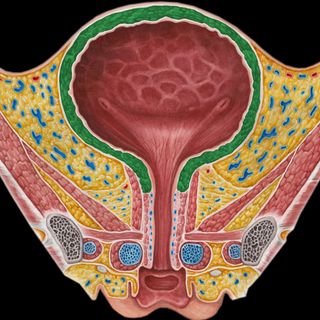

Why Women Are More Prone to Urinary Tract Infections Than Men