Surviving the Pandemic Has Made Us Kinder, More Aware of Mental Health. Will It Last?

“It’s hard to say whether the Covid19 crisis has made us more empathetic in the long-term. But what’s undeniable is this: 2020 has revealed the importance and strength of empathy in our day-to-day interactions.”

Last week, Smriti Irani, the Union Minister of Women and Child Development in India, shared a post on social media, which said, “When I was a kid, they didn’t take me to a psychologist… My mom was able to open my chakra, stabilize my karma, and clean my aura with one single slap.” Following tremendous backlash for dismissing mental health and promoting violence against children, she took the post down.

As despicable as the post may have been, it does echo how most Indian parents view mental health — or, perhaps, view-ed it. The global tragedy titled “Covid19” that has been unfolding since 2020 may just have altered people’s — and even boomer parents’ — perceptions about mental health.

Siddhi, 25, notes that her parents have begun understanding her need for space and don’t question her for locking her room anymore. Charan, 20, too witnessed a change in her parents’ attitude towards mental health during the pandemic. “My parents have started to be more mindful about how I’m juggling studies and work, and ask me to take a break and go for walks every now and then,” she says. Siddhi’s and Charan’s experiences denote a colossal evolution in our perception of mental health from just a couple of years ago when many Indians couldn’t even tell their parents they were in therapy without being judged or berated.

This pandemic-inspired empathy has seeped into other relationships as well. “My friends now understand when I say I don’t want to go out — they don’t force me, or insist that I do something I’ve said no to. No one just suddenly drops by at home anymore; we always call first and ask if they’re in a state to meet,” Siddhi notes, adding that even “when making plans, we ask each other, ‘Are you comfortable doing this?’ And we actually mean it.”

Charan mentions paying back the compassion she has received. “Earlier [if a friend didn’t want to spend time with me], my reaction was to think that, maybe, they don’t want to stay friends with me anymore, or don’t care enough about us, and so on. But now I’ve found myself asking them questions about how they are feeling, and if they would prefer a one-to-one chat instead of a party,” she notes.

Related on The Swaddle:

India Ranks Low on Index Measuring Small Acts of Kindness to Strangers

Varsha, 29, experienced greater respect for her emotional boundaries in her dating life too. “If the person feels upset, or uncomfortable, or low, we are allowing them to be upset [without] mak[ing] a fuss about it, or… poking them with questions like, ‘What’s happening?'” she had told The Swaddle last September. However, this does not imply that people care less about each other now; instead, it reflects a willingness to give others space. “We do make efforts to make things lighter… by discussing random, silly things, or sending each other short videos. But earlier, we weren’t given the space to feel sad at all. There was this unsaid assumption that if the person is not feeling well, it becomes my duty and my responsibility to make them [better],” Varsha said.

Mark Sholars, a writer, believes we’re in the “middle of a sea change in… how we treat each other,” even in capitalist workplaces. He points out the marked departure from saying things like “It’s not personal, it’s just business,” which revealed “the not-so-secret attitudes that modern workplaces have had towards anything emotional: keep your feelings at home and do the job.”

Now, as Samriti Makkar Midha, a Mumbai-based psychotherapist, notes, organizations have introduced measures like “mental health week-off, no calls on Fridays, or not having meetings after certain hours” to take care of the emotional well-being of their employees. Given that one in every three Indian professionals was found to be dealing with work-related burnout during the pandemic, measures like the ones Midha mentioned are, perhaps, the need of the hour. In fact, recognizing this need, the Portuguese government even passed a law stating that employers there can now be penalized for contacting their employees after work hours.

But how did the pandemic manage to do what all the textbooks talking about kindness in our formative years couldn’t? The “mass trauma” we underwent through the course of the first and second waves — marked by a collective sense of grief, anxiety, sadness, alienation, and isolation — has helped us acknowledge and understand what people around us might be going through too. Basically, surviving this almost-apocalyptic global event together has led us to resonate with the experiences of others without dismissing their struggles by saying, “You have a good job, you have a good family — what’s there to be upset about?” Midha explains. The pandemic taught us that “people can feel low, without having a very specific reason for it,” she adds.

In addition, the stigma around mental health beginning to dissipate has also allowed people to feel less hesitant about seeking therapy or even for asking their employers, families, and friends to accommodate their mental health. In a way, by setting and respecting boundaries, we’ve come closer.

“Treating [mental health] at par with physical disorders is a step we are yet to take as a society… But the conversations we have begun having [on mental health] are already helping me talk about my depression a lot more often now,” Olipriya, 18, says.

Related on The Swaddle:

Training Young People To Be More Empathetic Could Reduce Violent Crimes

The question now is: is this a lasting change? Stephanie Preston, a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, believes that it’s unlikely the empathy we’ve begun to exhibit “will completely dissipate as we move further from the intensity of the pandemic.” However, she believes the “degree of compassion we have for each other may waver and vary,” as compassion fatigue sets in and the memories of living through the traumatic event begin to fade.

But Midha believes that “the fact that these conversations have started right now, and people are picking up on them” is a positive development and, perhaps, the conversations will continue to linger in the consciousness of society — at least, among the youth– for years to come. She also adds that “every second or third person [wanting] to pursue mental health as a profession and become a psychologist,” may also have a lasting change on how much we, as a society, care about mental health. If nothing else, perhaps, it will contribute to fixing the dismal mental health professional-to-people ratio in India, to some extent.

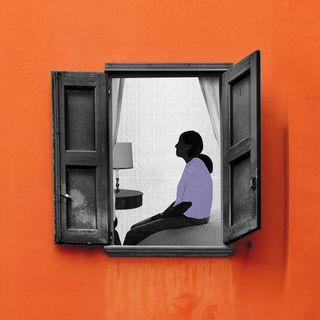

The pandemic has also made people more empathetic towards themselves and improved the way they spend solitary time. “I do find myself taking breaks more and seeking things without assigning a productive value to them — such as creating art for the sake of art; or writing poetry, but not necessarily to post it [on social media]… Some things just for myself, and for my sanity,” Apoorva, 22, says. Even if we forget what the pandemic felt like, perhaps, the way we connect with ourselves will be able to stand the tide of time — and, hopefully, also reflect in how we treat others.

The solution, then, lies in not just hoping that things continue to stay the same, but also carrying our lessons from the pandemic forward and actively practicing empathy. Perhaps, coming up with more flexible work models — as companies have already begun doing with hybrid options — can help make compassion sustainable.

But ultimately, as Sholars wrote, “It’s hard to say whether the Covid19 crisis has made us more empathetic in the long-term. But what’s undeniable is this: 2020 has revealed the importance and strength of empathy in our day-to-day interactions.”

Devrupa Rakshit is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She is a lawyer by education, a poet by accident, a painter by shaukh, and autistic by birth. You can find her on Instagram @devruparakshit.

Related

The Pandemic Has Changed Intimacy For Good