The Assam Government Sealed a Museum Dedicated to Bengal‑Origin Muslims

The move highlights how the state and dominant communities gatekeep culture, undermining marginalized communities’ claim to it.

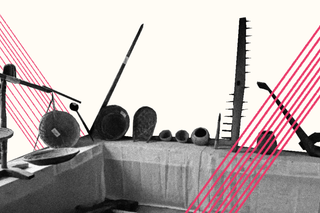

The Assam Government on Tuesday sealed a museum dedicated to the Bengal-origin Muslims of the state, barely two days after it was inaugurated, The Indian Express reported. The museum displayed antiquated items from the daily lives of “miya” communities — farming and fishing tools, clothes, and food. Located in the Goalpara district of the state, the museum was sealed by the local administration on the grounds that it was set up in a house allotted under the government’s Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana – Gramin scheme. Three members of the Asom-Miyan (Asomiya) Parishad, the organization that set up the museum, were arrested by the Assam Police in connection to a separate case filed last week. According to a report by Scroll.in, they have been charged under provisions of the highly controversial Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA).

The series of incidents highlight how the state and dominant communities gatekeep culture, undermining marginalized communities’ claim to it.

The community in question carries a cultural history loaded with exclusion and xenophobia — which makes the museum’s closure a continuation of the same. In Assam, “Miya” or “Miyan” has long been a pejorative term to refer to the Bengal-origin Muslims of the state. Starting from the nineteenth century till the 1971 Bangladesh liberation war, Muslims from Eastern Bengal (present-day Bangladesh) settled in the char-chaporis or low-lying flood plains and islets of Assam in several waves of migration. Over the years, as “anti-outsider” sentiments have grown in the state — beginning from the Assam movement in the 1980s to the recent exercises of updating the National Register of Citizens (NRC) — these Muslims became the most identifiable “out-group” and thereby the easiest targets of the ethnonationalist politics and violence in the state. “Miya” thus became shorthand to refer to these Muslims as undocumented Bangladeshi immigrants who must be identified and deported from Assam.

In recent years, however, voices from within the Bengal-origin Muslim communities of Assam have reappropriated the term to denote their group and their distinct culture and lifestyle. For instance, in a 2020 conversation with Scroll.in, Sherman Ali Ahmed, a 55-year-old politician and legislator, said, “Since they are deriding us by calling us Miya, so we said ok, we are Miya…It is a kind of rebellion; now this miya word is almost unanimously accepted. It is important to have a distinct Miya identity.” Educated Miyas have also decided to use their own language to communicate and write literature, documenting in poetry their unique experiences of always being treated as second-class citizens in a land they have lived in for generations. The NRC, court cases, discrimination, and oppression are key themes of Miya poetry.

However, Miyas reclaiming a once-pejorative term to assert as opposed to hiding from their distinct identity has caused further ire among nationalist Assamese people.

Himanta Biswa Sarma, Chief Minister of Assam, commented that the museum in Goalpara was not showcasing anything unique about the Miya community’s culture. “Let them prove before the government that the langol [plough — one of the items showcased in the museum] was used by Miya people alone. If they can’t do that, a case will be filed,” Sarma was quoted by The Indian Express as saying. Sarma’s comment ignores the fact that often, different communities sharing similar geographical conditions use similar tools and a shared culture for their survival.

Related on The Swaddle:

Assam Eviction Drive Displaces Over 800 Muslim Families

The Assam government’s attitude toward Miyas, moreover, highlight how the state and state-backed dominant communities in a region gatekeep culture and undermine marginalized communities’ access to it.

The museum isn’t the first instance of cultural erasure with respect to Bengal-origin Muslims in Assam. In 2019, both right-wing politicians and noted Assamese public intellectuals displayed their anxieties against the growing popularity of Miya poetry. Pranabjit Doloi, a journalist, filed an FIR against Miya poets for “causing unrest,” citing the charged themes and content of their poems, while others questioned the very need for the Miyas writing in their own tongue. As residents of Assam, they were expected to prove their loyalty to the state by completely giving up practising their own language and assimilating with the “local” population.

Similarly, in 2020, when Ahmed first demanded that the government set up a museum (not connected to the museum in Goalpara) documenting the life and culture of the Bengal-origin Muslim residents of the char-chaporis, Sarma — then a prominent minister in the government — tweeted then that “…there is no separate identity and culture in Char Anchal of Assam as most of the people had migrated from Bangladesh.”

Assam is a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural state with a Hindu, Assamese-speaking majority. According to the 2011 Census, Muslims made up only a little over 34% of the state’s population, but this number has been enough to heighten anxieties around demographic takeover by the Muslim community. On the other hand, as mentioned above, the state also witnesses a mass anti-outsider sentiment, with many political parties and pressure groups being harsh on other linguist groups. In such a situation, Bengal-origin Muslims face isolation both due to their religion and their language. And this allows every party to rabidly highlight how “Miya” Muslims are different from all other communities in the state, allowing them the easy dog whistle to ask members of the “Miya” community to “assimilate” in order to “allay these fears.”

The state and caste-Hindu Assamese society’s response to Bengal-origin Muslims asserting their identity, therefore, has been to emphasize the notion of a homogenous Assamese culture, one which erases marginalized Bengal-origin Muslim communities. In fact, Assam actively distinguishes between “indigenous” Assamese Muslims and Bengal-origin Muslims on these grounds, doubly identifying the latter as different not only from the majority Hindus of the state but also different from the other indigenous communities and even from other Muslims.

But, as the state’s reaction to the current museum in Goalpara shows, even attempts at “assimilation” would ultimately be discouraged by the state. The Asom-Miyan (Asomiya) Parishad wanted to highlight that Miyas are similar to other communities residing in the state. Mohar Ali, one of the members of the Asom-Miyan (Asomiya) Parishad who was eventually arrested, was quoted by the Press Trust of India stating that they “are displaying objects with which the community identifies itself so that people from other communities can realise that the Miyas are not any different from them.”

Amlan Sarkar is a staff writer at TheSwaddle. He writes about the intersection between pop culture and politics. You can reach him on Instagram @amlansarkr.

Related

Why David Attenborough’s Environmentalism Is Flawed