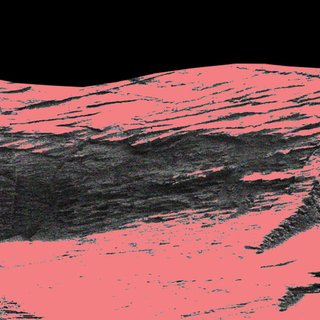

There’s a supermassive black hole at the heart of our own galaxy — and now, we know what it looks like. Half-a-century ago, astronomers detected a strong source of radio emissions from the Sagittarius constellation— Sagittarius A*, the name given to the speculated black hole, has been the subject of much scientific curiosity ever since.

We’ve deduced since then that this is a black hole, but thanks to the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), we can now look at the colossal “monster” at the center of the Milky Way in the flesh — or void, as it were.

This is a milestone for two reasons. It is the second picture ever taken of any black hole, and the first of the one in our galaxy. The first picture was taken in 2019, of the black hole at the Messier 87 (M87) galaxy 50 million light-years away — another supermassive one that contains the mass of 6.5 billion suns.

Sagittarius A* is a smaller one; four million times the mass of our sun, and only about 26,000 light-years away — still a considerable (and safe) distance away from us. “This is in ‘our backyard’, and if you want to understand black holes and how they work, this is the one that will tell you because we see it in intricate detail,” Heino Falcke, who pioneered the EHT project, told BBC News.

The finding is special because it confirms the theory that the source of immense gravitational forces, making nearby stars speed along at incomprehensible speeds, is indeed a supermassive black hole. The picture, in other words, is hard evidence of what was still a hypothesis. “This result provides overwhelming evidence that the object is indeed a black hole and yields valuable clues about the workings of such giants, which are thought to reside at the centre of most galaxies,” the EHT team said.

Related on The Swaddle:

Milky Way’s Supermassive Black Hole Has Suddenly Started Swallowing More of the Galaxy

To put this into context: in 2020, two astronomers Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez received the Nobel Prize in Physics for their work on a “supermassive compact object at the center of our galaxy” — short of calling it a black hole, since we still couldn’t be absolutely sure.

The EHT itself is not a single, composite telescope, but eight radio observatories across the world whose combined observations are such that an Earth-sized telescope would produce. The other reason why the image is special, even if it’s the second one of a black hole, is that its similarity to the one taken in M87 can add further weight to the explanatory theories of the universe. “This tells us that General Relativity governs these objects up close, and any differences we see further away must be due to differences in the material that surrounds the black holes,” said Sera Markoff, Co-Chair of the EHT Science Council.

Despite the fact that M87 is much further away, it was much easier to capture that first. It has to do with the gas rings whirling around the black hole — with M87 being much bigger, the gas takes more time to orbit it than it does Sagittarius A*. This means that telescopes have a much harder time capturing this latter, more unsteady object.

Now that we have images of two different supermassive black holes, it gives us an opportunity to learn more about how gas behaves around them and, consequently, how galaxies themselves are formed.

“We have images for two black holes — one at the large end and one at the small end of supermassive black holes in the Universe — so we can go a lot further in testing how gravity behaves in these extreme environments than ever before,” said EHT scientist Keiichi Asada from the Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Academia Sinica, Taipei.

This August, the newly launched James Webb telescope will train its gaze on Sagittarius A*. It’s the best and move advanced space telescope we have out there now, taking over from its predecessor, the Hubble telescope. “Every time we get a new facility that can take a sharper image of the Universe, we do our best to train it on the galactic center, and we inevitably learn something fantastic,” Jessica Lu, from the University of California, Berkeley, told BBC.