The First Synthetic Human Embryos Are Here — Are They Ethical?

The ability to create embryos in a lab gives rise to ethical challenges that law — and the scientific community — is yet to address.

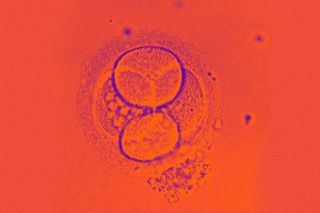

In a groundbreaking development, a team of scientists from the U.K. and the U.S. have created synthetic human embryos by reprogramming stem cells — circumventing the need for sperms and eggs, in the process. These are model embryos, they note, that are at the very initial stages of human development, and can help advance the study of genetic disorders and improve understanding of the causes of miscarriages. While they, reportedly, lack most internal organs, they do include cells that would eventually form the placenta, yolk sac and the final embryo.

“[T]hey are very exciting because they are very looking similar to human embryos and very important path towards discovery of why so many pregnancies fail, as the majority of the pregnancies fail around the time of the development at which we build these embryo-like structures,” Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, a Polish-British developmental biologist whose lab has been involved in the development, told CNN.

While Zernicka-Goetz has stressed that “they are not human embryos… [but merely] embryo models,” the ability to create embryos in the lab gives rise to ethical challenges that the scientific community is yet to address. The Guardian has reported that the creation of these embryos falls outside the ambit of present legislations in several countries. And so, one of the central ethical concerns surrounding the development pertains to the inherent dignity and respect owed to human life: the absence of eggs and sperm may diminish the perception of these embryos as fully human. At what point do these entities attain moral — if not legal — status?

“If the whole intention is that these models are very much like normal embryos, then in a way they should be treated the same… Currently in legislation they’re not. People are worried about this,” flagged Robin Lovell-Badge, the head of stem cell biology and developmental genetics at the Francis Crick Institute in London.

Granted, at the moment, the embryos neither have a beating heart nor a functioning brain. Whether or not they’d be able to develop further and grow into living, breathing entities is also suspect. In fact, in the past, when similarly created monkey embryos were implanted into the uteruses of adult monkes, they experienced a short-term pregnancy that ceased to proceed beyond a few days. But how long before scientists are able to figure out why and resolve it? Scientists have claimed, though, that there is no plan to use the synthetic embryos clinically in the near future, with Lovell-Badge saying, “The idea is that if you really model normal human embryonic development using stem cells, you can gain an awful lot of information about how we begin development, what can go wrong, without having to use early embryos for research.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Artificial Wombs to Enhanced Babies, How Ethical is the Future of Birth?

But is it really that far-fetched to imagine a future when we expect more from this advancement? And so, the development also sparks anxieties regarding the potential misuse of the technology to create “designer babies,” perhaps. The concern isn’t entirely unfounded in a world where embryo menus — allowing people to pick and choose from an assortment of embryo descriptions like: “40% chance of coming in the top half in SAT tests,” “dark eyes, light brown hair, [but with a chance of] male pattern baldness,” and “lower than average risk of asthma and autism” — are already a thing. The fact that experiments to create genetically modified human embryos using the gene-editing technique, CRISPR, are also underway, merely aggravates apprehensions.

The vast ethical landmine surrounding gene-editing has already triggered debates within the scientific community — putting forth concerns about the technology contributing to societal inequality since advanced technologies like CRISPR will not be be affordable for many. This applies to the creation of synthetic embryos, too. Since access to the latest advancements in scientific research is restricted by means of significant financial and technological barriers, they are often limited to a privileged few — exacerbating social inequalities and potentially reinforcing existing power imbalances.

It’s, indeed, possible, that we may be getting ahead of scientific advancements themselves with our concerns, much like “the science in this field has outpaced the law.” But without appropriate ethical frameworks and regulatory oversight, this groundbreaking scientific development heralds a risk of sliding down a slippery slope, where boundaries between research and reproductive practices become blurred. In other words, the speed of the scientific developments is precisely why it’s important to prepare for potential exploitation.

“Most countries have not yet legislated on genetic modification in human reproduction, but of those that have, all have banned it,” The Guardian had noted, adding: “The spectre of a harsh, impersonal and authoritarian dystopia always looms in these discussions of reproductive control and selection.”

Devrupa Rakshit is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She is a lawyer by education, a poet by accident, a painter by shaukh, and autistic by birth. You can find her on Instagram @devruparakshit.

Related

With Deepfake Porn and God Chatbots, AI Dystopia is Here