Author Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni on the Value of Epics in the #MeToo Era

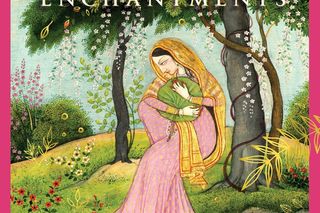

In ‘The Forest of Enchantments’ Divakaruni’s Sita resists the stereotype of the meek, dutiful Indian wife.

Ten years after Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s retelling of the Mahabharat, The Palace of Illusions, the prolific writer has published a sister novel, The Forest of Enchantments. The book retells the Ramayan in a way that affords its characters, especially the women, a lot more complexity than our pop culture versions allow it. In conversation, Banerjee Divakaruni discusses this latest novel, the legacy of Sita, and what she means for Indian womanhood today. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Swaddle: In your author’s note, you described writing this novel as “the most challenging project of my life.” What was it about this project that was challenging for you?

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, author of The Forest of Enchantments: Several things were particularly challenging. First, I wanted to retell the story of one of our most revered epics, so I felt a lot of pressure to do it well, with the right combination of respect and inquiry; and second, I wanted to center the novel on Sita and bring out unique angles of her character, which I felt had become obscured over time due to patriarchal retellings. But I didn’t want to depart from the main lines of her story as presented by the Ramayan. So, I was operating within pretty tight constraints.

The Swaddle: Can you walk us through a bit of your process for this book? What was it like researching and writing such a well-known epic? Were there sections or characters that were more difficult to write than others?

CBD: It was a daunting process because there are so many Ramayans. Valmiki, Kamba, Tulsidas, Adbhuta, Kriitibasi. And that’s just a few. They focused on different aspects of Sita that were fascinating and illuminating. And of course there were challenging scenes where Sita faces great danger and sorrow. I wanted to be able to do them right. Particularly difficult was when Ram banishes a pregnant Sita to the forest without even telling her what he is doing. It took me a long time to be able to grapple with that.

“I wanted to show Sita in her graceful strength, but also as a woman like all of us. “

The Swaddle: There’s this idea that’s peppered throughout the book, and finally confirmed when Sita is told, “He [Ram] has come to teach the men, but you have come to teach the women.” I wonder what you think about Sita’s relationship to Indian womanhood today. Her tenacity, wisdom, and grace certainly come through in your version of Sita, who is incredibly strong. But there’s also a tension there, since she’s also been a figure of the ideal, dutiful Indian wife for so long.

CBD: Yes. There is tension. I wanted to show Sita in her graceful strength, but also as a woman like all of us. Joking with her sister, falling in love with Ram but also seeing his faults, maneuvering palace politics, longing for the golden deer as a substitute for the child she is not allowed to have, etc. Also when she is heartbroken and furious because the husband she loves so much doubts her fidelity. And when she makes her final, difficult choice to refuse the agni pariksha because in spite of how much she loves her family, she refuses to compromise — for the sake of her “unborn daughters,” women of the ages to come. I hope my Sita embodies the fact that it is fine for women to have all these emotions.

The Swaddle: Relatedly, is there a message for Indian men in this book? Sita knows that, in order to portray her story, she must also portray the stories of all the other women in this epic, whose roles are so often minimized and misunderstood. But what of the men? Is there something to take away from this version of Ram or Lakshman or Ravan?

CBD: It is a novel, so I don’t want to impose any messages. I want both men and women readers to decide what is their own takeaway. But I hope men will be moved by Sita’s situation and her words, and become sensitive to the plight of women in similar situations. Women who have been abducted or are victims of violence. How they are often pushed to prove their innocence. Or shamed for their plight. Also, I hope they will be aware of times when the public roles and values that men adopt lead to deep problems. Ravan feels he cannot return Sita to Ram; it would be cowardly and unseemly of him as a warrior. Ram feels he has to banish Sita in order to be an exemplary king. They both suffer for these decisions — and sadly, many others suffer along with them.

“If we cannot endure, we will be broken by our challenges.”

The Swaddle: How was the experience of writing this book different from your other books? I’m specifically thinking about The Palace of Illusions, since both of these projects were major undertakings, and the two epics are often held in tandem with each other. I think, personally, I’ve always found the Mahabharat more interesting as a story, because it’s so twisty and slippery, and the characters feel more complex than Ram, Sita and Laxman. Characters in the Ramayan feel like they’re essentially either good or bad. Since you’ve been thinking and working on The Forest of Enchantments for quite a long time now, I wonder if you have insights into the story and its many retellings. Is it not as black and white as it seems?

CBD: The Palace of Illusions was a little easier to write for the reasons you have pointed out. However, examining The Ramayan, I found that it is much more nuanced than we think. For instance, we have been taught to judge Ravan as evil and monstrous. But in Kamba Ramayan we find that he is learned and a great king loved by his people and a sincere devotee of Shiva as well. Both in Krittibas and Kamban we are shown the Soorpanakha episode in a way where we understand that she is a woman expressing her desire as is customary with her people, which makes her disfigurement by Lakshman much more troubling. Sita is always seen as the dutiful wife, but when Ram tells her to stay in Ayodhya and look after the in-laws, she responds with a very strong and spirited, ‘No way!’ There are many episodes like this.

The Swaddle: Endurance is a word that is repeated throughout the book, as something that women will always have to do, have to practice. The instance that stood out for me is towards the end of the book, when women surround Sita in her dream, telling her to endure: “Endure as we do. Endure your challenges.” It seems like a strange ask, almost contrary to our current cultural moment. Do you think there’s something we’ve misunderstood about the concept of endurance?

CBD: In my understanding, endurance is step one. If we cannot endure, we will be broken by our challenges. Once we have said to ourselves, ‘OK, this is happening; I won’t be defeated by it,’ then we can decide what is our next step. This is what Sita does when she is left in the forest, heavily pregnant. She grieves, accepts the situation (endures it), and decides she will bring up her boys by herself, being both mother and father to them. So, that is the kind of endurance I would like women to consider.

Related on The Swaddle:

Author Gayatri Rangachari Shah on Women Leading in Male‑Dominated Bollywood

The Swaddle: What value do these epics and myths have for us today? What happens when you retell a well-known story?

CBD: I have found great value in our epics and myths. They have taught me valuable lessons, given me joy and upheld me during my troubles. This is because the situations they depict are timeless and ever-relevant. And the characters are so complex and timely. For instance, both Sita’s situation in the Ramayan, and Draupadi’s situation in the Mahabharat, and their resistance to the patriarchal norms of the day can be a great inspiration to women involved in the current #MeToo movement. It is the writer’s job, though, to shine a light on the epic in the right way.

The Swaddle: That’s true — the trials of Sita seem incredibly relevant today, to the #MeToo movement and the way in which women are always burdened with the task of proving their own innocence (and how, even then, it is not enough). Sita’s final form of protest is to refuse to do the second agni pariksha and reject Ram’s offer of returning. I’ve always seen it as a tragedy, where she is so disappointed in her husband that she gives up her life — but you portray it as a kind of an act of resistance. Did you always see it as one? Can you elaborate a bit about how you wrote that final scene?

CBD: It was only as I was analyzing the story of the Ramayan and feeling it in my heart that I understood the true heroic meaning of Sita’s final act. I hope readers will feel it the same way and it will inspire their lives.

Nadia Nooreyezdan is The Swaddle's culture editor. Since graduating from Columbia Journalism School, she spends her time thinking about aliens, cyborgs, and social justice sci-fi. She's also working on a memoir about her family's journey from Iran to India.

Related

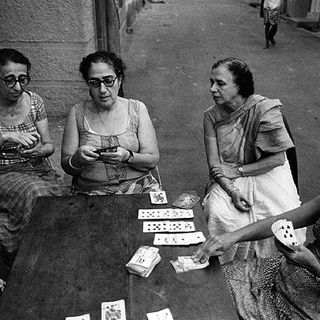

Kitty Parties Were Never About the Gossip; They’re About the Women