The History of the Sex Strike As a Form of Resistance

Denying men sex doesn’t by itself incite political change. But it sure does make them listen.

Withholding sex is an act pop culture gleefully tells us is a woman’s weapon wielded to get male attention — be it for getting more dates out of a potential partner, or as a way to make him apologize. As a society, we have struggled with the fantastical notion that women could have sexual desires similar to men’s, which perhaps has led to reductive portrayals of female sexual desire that can be easily bartered for anything else that women are supposed to desire more.

However misinformed this approach might be, historically, women have used this misconception to their advantage in the form of a passive political resistance called sex strikes. Recently, American actress and activist Alyssa Milano called for a sex strike in response to a regressive anti-abortion law passed in the American state of Georgia that would ban abortion after six weeks of pregnancy if approved. This is an impossible stipulation, as it roughly culminates in the woman knowing she’s pregnant after two weeks of a missed period (which happens to women all the time with no good reason, by the way). Milano rightly spoke up against the bill, but her form of agitation drew ire from many on social media, who questioned the inclusivity and patriarchal undertones of sex strikes.

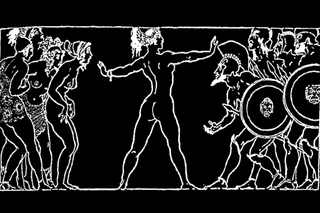

Targeting cis women who have sex with cis men leaves out lesbians, trans people and sex workers. And why do we need to consider sex as a transactional commodity anyway? That’s the reason we have come to think of sex as something women give, and men feel entitled to take. While all of these are valid critiques against sex strikes, women have still managed to use them to bring about political change for centuries — the first instance of this resistance apparently dates back to an ancient Greek playwright, Arsitophanes, and his play, Lysistrata.

In the play, the heroine mobilizes women and asks them to abstain from sex in the hope of ending the war between Athens and Sparta, a movement that, in the literature, becomes successful. Fast forward centuries, and women from the Native American Iroquois tribe in North America boycotted sexual intercourse and childbearing in the 1600s, a movement Milano cited herself. Their male partners were engaging in unregulated warfare and the women were having none of it; their sex strike was accompanied by a demand for more political power. As the men believed the women had a miraculous power to birth people, they acquiesced and gave the women veto power over all wars — a successful end to what is widely considered the first feminist rebellion of the United States.

The most popular and successful instance a sex strike is more recent, in Liberia. In 2003, the orchestrator of the sex strike, Leymah Gbowee, effectively used mass sexual abstinence as a tool in the greater peace movement to end Liberia’s bloody civil war, for which she received a Nobel Peace Prize in 2011.

“It’s effective in the sense that it gets people’s attention. Sex is an exotic thing, and many people would say it’s a taboo subject. But when someone dares to bring it to the attention of the public, it has two results. People start saying, “who’s this person doing this?” and they start asking why the person is using sex to highlight an issue. And it gets men thinking,” Gbowee told HuffPost. In a later interview with Slate, Gbowee didn’t overshoot the purpose of the sex strike: It wasn’t as if men felt deprived of sex for a couple of days and immediately bent the knee to all of their wives’ desires. “But it was extremely valuable in getting [the peace movement] media attention,” Gbowee said.

Related on The Swaddle:

Women’s Sex Drive Isn’t Lower Than Men’s; It’s Just More Variable

Many female activists of the world have followed suit. In the Colombian city of Pereira, the wives of local mobsters staged a sex strike to demand their husbands turn in their weapons to the government and enroll in a vocational training program to make something of themselves, The Guardian reported. While there exists no official end date for the strike, the people of the city attribute a steep decline in the murder rate — a dip of 26.5% — to the women who decided to take a stand, The Guardian reported. In another city in Colombia in 2011, women carried out an almost three and a half months of “crossed legs” sex strike, all for getting a road paved in their town.

In Kenya, women went on a seven-day sex strike in 2009 to make the opposing leaders of the Kenyan government stop squabbling with each other, and even tried to mobilize the politicians’ wives and sex workers to join — to get all the bases covered, BBC reported. “Great decisions are made during pillow talk, so we are asking the two ladies at that intimate moment to ask their husbands: ‘Darling can you do something for Kenya?’” BBC reported an activist saying.

Sex strikes, however, don’t always work. In Togo and Italy, for example, due to a lack of organization and a dearth in numbers, the Lystratic non-action, as it’s called in a nod to the play that inspired it, failed. It’s likely Milano’s call to go on a sex strike will also be unfruitful, mainly because her demand is to “get bodily autonomy back,” which is … vague. The sex strikes mentioned above succeeded because the women who engaged in the dissent had a clear idea of what they wanted.

Turns out the sex strike is like any other political action — it needs a strong conceptual foundation, a plenitude of protesters, and regardless of what they say about heterosexual women’s lack of sex drive, an insanely strong resolve.

Rajvi Desai is The Swaddle's Culture Editor. After graduating from NYU as a Journalism and Politics major, she covered breaking news and politics in New York City, and dabbled in design and entertainment journalism. Back in the homeland, she's interested in tackling beauty, sports, politics and human rights in her gender-focused writing, while also co-managing The Swaddle Team's podcast, Respectfully Disagree.

Related

Lessons From Four Decades of Fighting for Women’s Rights