The Last Courtesans of Bombay: A Crumbling Community

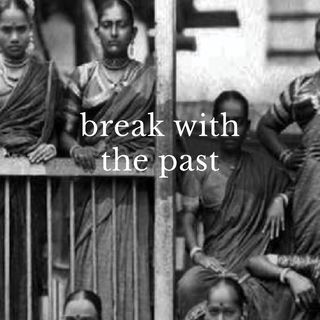

With Mujra in decline, a neighborhood that was once the nerve center of Bombay’s courtesan culture struggles to stay alive.

With Mujra in decline, a neighborhood that was once the nerve center of Bombay’s courtesan culture struggles to stay alive, in the final episode of our podcast series, The Last Courtesans of Bombay.

Previous episodes

Episode 1

Episode 2

Episode 3

English Translation of Episode 4: A Crumbling Community

Naseem Bhai: There were many shops selling perfumes. Perfumes used to sell very well, so there were lots of shops selling it. Not just perfumes, ladies’ accessories like lipstick, powder, etc. — there were shops selling these, too. But all those have shut now. The rent used to be Rs. 8,000 earlier; now it is down to Rs. 3,000. You can see, all those shops are shut now. Earlier, this road used to be bustling with activity, gleaming with lights.

Voiceover in English, amid mujra performers singing.

Woman 1: You come here to enjoy. It is my job to make you fall in love with me. If I don’t show you love, how will you feel love for me?

Woman 2: All my family members have cut off all ties from me because I entered this industry. They said, ‘We can’t kill her because, after all, it’s the family blood. We won’t be able to kill, so let’s cut off all ties.’

Man: At 4 am, when the whistle used to blow, the music would finally stop. Till then, every house would be lit up. But now, no one comes here. People can barely recover their rents. There is no business here, how can people run shops here?

Voiceover in English.

Host Kunal Pirohit: Can you tell me a bit more about the ambiance back then? Would it be as dark as it is right now?

Naseem Bhai: No, no. The ambiance and illumination then … till 4 am, when the performances finished and the final whistle was blown, till then, there would be lights outside every house. People would also use some flower garlands with these lights to decorate the outside of their houses. Each house’s decoration was distinct. There would be vendors selling flowers, walking around applying mehndi (henna), some vendors would walk around selling snacks in small pouches. It felt as if a market was setting up at 4 am, as soon as people got free from the performances.

There was a café here, Sardar Hotel, which would remain shut through the day but make up for its business in those few hours of the night. There would so much activity even at 4 am that no one would feel scared, walking around. So, as soon as the performances ended, all these vendors would come. There used to be many taxis in the area to drop the performers to their homes. Often, when we couldn’t fall asleep, we would listen to the whistle and know it’s 4 am and it was time for us to sleep.

Voiceover in English.

Naseem Bhai: Back in the day, this hotel used to be so busy that it would be impossible to buy seekh kababs from here! There used to be long queues of people from all over the city, because Sayyed’s Seekh Kebabs were so famous. Both, patrons, as well as visitors, would spend money in the neighborhood, eating, shopping, drinking.

Voiceover in English.

Naseem Bhai: We had appointed Ismail Bhai, whose job was to blow the whistle at 4 am each morning. The whistle meant all performances had to stop immediately. Then, after 9 to 10 am, people could start performances again. So, even if your patrons insisted that they wanted to listen to performances at 4 am, you could not perform. Performers would tell such patrons to wait for a few hours. The rule was clear — no matter who the patron is, no matter how he was paying, you could not perform beyond 4 am.

Voiceover in English.

Naseem Bhai: One of the best things about the community is that ‘time’ — time is what they called mujra — during ‘time,’ if someone died, then the mujra would shut down for a day. No matter who died, whether it was in the immediate neighborhood, or someone in the family of the performers, the mujra would remain shut for a day as a mark of respect. That day, even if the wealthiest man in the city came to your door, you were not allowed to perform. You could offer him tea and a snack, but you were not allowed to perform.

Voiceover in English.

Interview with Anna Morcom in English.

Voiceover in English.

Naseem Bhai: In the jalsa (celebration), the performers of the neighborhood would sing and dance. This was done in the open. These performers would not charge for it. All the money that was collected was donated to whatever was the occasion — an urgent humanitarian cause, a terror attack, or if a family did not have enough money to get their daughters married.

Voiceover in English.

Naseem Bhai: After a death in the neighborhood, or even during Muharram, for all 12 days, these performers still hold langars (free communal kitchens), where free meals are given to anyone who comes, no matter what faith they belong to. All performers and kothas pool in money and contribute, depending on what they can afford.

Voiceover in English.

Interview with Anna Morcom in English.

End of series.

Also available on:

Kunal Purohit is an independent journalist, writing on politics, gender, development, migration and the intersections between them. He is an SOAS alumnus. He has previously written for the Hindustan Times, The Times of India, and The Wire, among other publications. He tweets at @kunalpurohit.

Related

The Last Courtesans of Bombay: A Poet’s Taleem