The Men Helping Other Men Challenge Toxic Masculinity

NGOs are providing gender sensitivity training to men to make society safer for everyone.

For the longest time, women have been solely responsible for ensuring their own safety in public. Clutch your keys at night while walking down a dark alley; take a self-defense class to feel safer; avoid wearing skimpy clothes in shady areas — such advice abounds from all corners of a woman’s world, be it from family, friends, strangers on the internet, or even from the government. Basically, the message is: You are the only affected party in this culture of violence against women, so the onus is on you to fix it.

This message is driven home by the type of solutions offered by social institutions. For example, under the Nirbhaya Fund Scheme created by the Government of India, 7,800 women of the Kangazha village in Kottayam between the age of 10 and 60 trained in self-defense against the threat of assault. There is now a pan-India number, 112, that is a part of the Women Safety initiative of Emergency Response Support System (ERSS). Women can either use the number, available in 16 states/union territories, or press the Panic Button on the 112 India Mobile App, in case of an emergency. In the private sector, emergency response initiatives such as the Watch Over You app have a special women’s safety feature, which claims to be “a personal Guardian Angel that oversees women when they travel or feel threatened.” India’s popular bus service, BEST, received a Rs. 10-crore grant from the government to operate women-only buses to ensure safety. We now have women-only police stations and squads, doing the work of sensitization and protection.

Notice a pattern? Every single “solution” is targeted at changing the habits of women.

There is no denying these initiatives will help some women, but for systemic, societal change, “we need to do something that is more long-term,” said Anand Pawar, executive director of Samyak, a Pune-based resource center that creates awareness of toxic masculinity and gender issues. “Technology cannot be the solution to patriarchal control.”

The effective solution would be to shift some of the responsibility of ensuring safety away from women. One of the ways Samyak has accomplished this is by challenging men’s risk-taking behavior, such as road rage, exercising control over women’s bodies, and reckless sexual encounters, which Pawar said epitomizes toxic masculinity tropes of aggression and competitiveness. “In many of our workshops, men did say that those who do not beat their wives are lesser men. This toxic definition of manhood pushes men to these behaviors. Men have created the definition of manhood, and they kept it so high that now they are just trying to reach it, but cannot.”

These behaviors all pose a risk to the man’s well-being as well, Pawar said. He risks sabotaging his relationships, health and life by engaging in them. Samyak workshops explain the detrimental consequences — for the men and for the people around them — of these behaviors, Pawar said. It is important to inculcate within men that “the dominant idea of manhood is not the only idea of manhood,” he said.

In his experience, it has never been enough to just empower women. In South Asia, “we need to understand that empowered women are not promoted to another planet;” they still have to exist within the patriarchal framework of society, he said. To flip the narrative, let’s teach men how to live with independent women and address men’s anxieties and insecurities surrounding gender equality and sharing their privilege, Pawar said. With Samyak, “the focus is on creating non-threatening environments for promoting equality. If your pedagogy is not creating a threat for men, many of them do come forward and express their desire to change,” he added. “We help them understand their privileges and the losses they might incur because of their urge to maintain those privileges.”

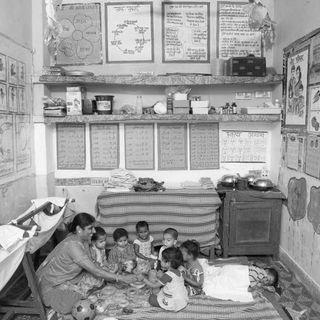

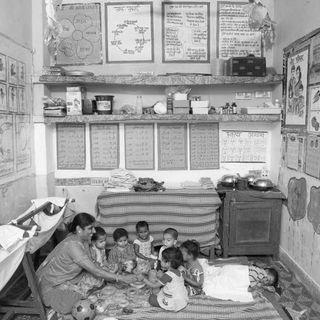

Through workshops, graphic design classes, film festivals curated around gender issues, and awareness campaigns targeted at young boys, adolescents and grown men, Samyak promotes gender sensitivity, Pawar said. Its 20 gender trainers discuss the concept of gender constructs with attendees, and how toxic masculinity controls mobility, resources and people, including members of the queer community, he said. They also reach out to fathers, especially, to encourage emotional connections with their sons and make them aware about patriarchal control of households, he said.

For example, 45-year-old Nivas Varape had never given a second thought to his daughter’s higher education, until he attended a Samyak workshop. He has already made arrangements to educate her further, he said, with a hint of pride in his voice.

“A lot of men might have learned the language [around feminism] but they didn’t learn the power relations. There is usually a very symbolic, and not a real, change. We train men to reflect on their notion of masculinity and their experiences with power and privilege, rather than going out and patronizing women,” Pawar said.

Other grassroots organisations doing similar work include Men’s Action to Stop Violence Against Women (MASVAW), a coalition of male activists in Uttar Pradesh working to create awareness among men about domestic violence and mobilizing men to protest such violence and support survivors. Another NGO called Men Against Violence and Abuse (MAVA), active for more than 25 years, hosted a travelling film festival in 2018 that tackled gender discrimination and promoted the concept of gender in a pluralistic, non-binary way across the country.

Baliram Jethe, 34, is a government employee living in the village of Fulwadi in Maharashtra. He first attended a Samyak workshop more than a decade ago, after he felt disgruntled with the child marriage and sexual assault cases around him. “I felt that this should be changed. But how do you do it? How far do we have to go?” Jethe asked, relaying his confusion at the time. “If we want to see change in the next 100 years, we need to start now.”

For Jethe, sensitivity workshops helped change the meaning of masculinity. When he was younger, he indulged in aggressively competitive, risk-taking behaviors, such as traversing dangerous farmland at night to grow more crops than his neighbor. “Finally, I asked myself — who are we competing against? My manhood is not going to be destroyed if [my neighbor] grows more crops,” he said. Additionally, gender sensitivity helped him get rid of unnecessary pride, which Jethe said improved his connection with his wife and enabled him to ask her for help when needed. In turn, he also felt more supported in his relationship, he added.

“Manhood is about talking to women, listening to women. We shouldn’t feel like we have to fix everything. It is about controlling anger. Feeling like I can do whatever I want when I’m angry, that is not manhood,” he said.

After years of training, Jethe runs his own workshops. A recent initiative is to go to schools and ensure teachers aren’t assigning stereotypically gendered activities and duties to students. He also talks to young boys about contraception, and how women are unfairly burdened with the responsibility. “A lot of youth want to change, but nobody is talking to them,” Jethe said, stressing the need to repeat the same narrative until it drives the point home.

“The issue is not about men and women,” he said. “It is about right and wrong. If only women talk about equality, then people will discredit her and say ‘Oh, she’s just talking about herself.’ If men start talking about it, then they’ll say ‘Oh, a man is talking. Let’s listen to him.’

Since that’s the case, we might as well say something worthwhile.”

Rajvi Desai is The Swaddle's Culture Editor. After graduating from NYU as a Journalism and Politics major, she covered breaking news and politics in New York City, and dabbled in design and entertainment journalism. Back in the homeland, she's interested in tackling beauty, sports, politics and human rights in her gender-focused writing, while also co-managing The Swaddle Team's podcast, Respectfully Disagree.

Related

India’s Rural Women Bear the Brunt of Jobs Crisis