The Plague May Have Shaped Our Present Immunity

Genetic variations that helped resist the plague might be increasing people’s susceptibility to autoimmune diseases today.

In the 14th century, the Black Death – a bubonic plague pandemic – swept across Europe, Asia and Africa. Caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, it claimed the lives of an estimated 30-50% of the population in Europe and was recorded as the most fatal pandemic in history. Now, scientists have found that the Black Death has left more of a mark on human health than they first thought – it could still be shaping people’s immunity, over 700 years later.

Researchers found that survivors of the plague had genetic variations that helped protect against the Y. pestis. But these variations have now been linked to a heightened risk of autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease.

The genetic variations that allowed some to resist the Black Death have continued to evolve over the years. A study published in the journal Nature shows how the intergenerational effects of past pandemics mold our susceptibility to disease and shape human evolution.

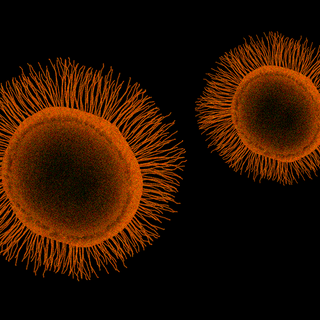

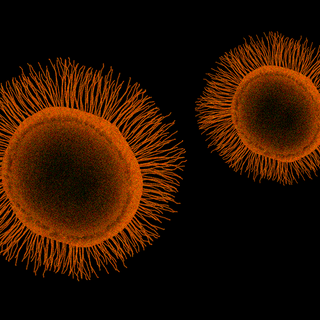

Our immune systems evolve over time to respond to different pathogens. In this case, the copies of genes that protected against the plague in the mid-1300s are still prevalent among today’s population, having been passed down over generations.

The researchers analyzed over 500 samples of DNA that were extracted from the teeth and bones of human remains in London and Denmark, even those found in London’s East Smithfield plague pit that was used as a mass burial site. The samples were drawn from individuals, both victims and survivors, who had died either before, during or after the Black Death.

With infectious pathogens being among the “strongest selective forces” that shape the human genome, the team of researchers were looking for signs of genetic adaptations to the plague. They identified four genes – including ERAP2 – that produce proteins to protect our bodies from pathogens, and found that variations of these genes – called alleles – protected or increased people’s susceptibility to the Black Death.

Individuals with one or more of these gene variants seemed more likely to have survived the plague. Two copies of the “selectively advantageous” ERAP2, for example, had allowed “more efficient neutralisation of Y pestis by immune cells.”

“When a pandemic of this nature – killing 30 to 50 per cent of the population – occurs, there is bound to be selection for protective alleles in humans, which is to say people susceptible to the circulating pathogen will succumb. Even a slight advantage means the difference between surviving or passing. Of course, those survivors who are of breeding age will pass on their genes,” explained Hendrik Poinar, evolutionary geneticist and an author of the paper.

“The evolution is faster and stronger than anything we’ve seen before in the human genome… It’s really a big deal. It shows what’s possible [for humans], in terms of adaptation in response to many different pathogens,” evolutionary biologist David Enard at the University of Arizona told NPR.

Related on The Swaddle:

Bubonic Plague Increased Immunity in Future Generations, Research Suggests

There are several implications of this.The presence of the “good copy” of ERAP2 meant a person was 40% more likely to survive the plague. This 40% advantage is the “strongest selective fitness effect ever estimated in humans,” Luis Barreiro, geneticist and an author of the study, told BBC News. However, ERAP2 is also a known risk factor for Crohn’s disease – an autoimmune condition – and has also been associated with other infectious diseases, the researchers noted.

Moreover, Enard, who was not a part of the latest study, further explained that the strongest example of natural selection in humans, before this one, was a mutation that increased lactose tolerance in Europeans. This ability to digest milk however, developed over thousands of years and offered very few percentage points of advantage.

Barreiro said that the selective advantage associated with the genes was “among the strongest ever reported in humans showing how a single pathogen can have such a strong impact to the evolution of the immune system.” He further told The Guardian, “This is, to my knowledge, the first demonstration that indeed, the Black Death was an important selective pressure to the evolution of the human immune system.”

A limitation of the study is that it focuses solely on people from London and Denmark – a narrow sample size, NPR reported. The Black Death affected populations beyond Europe, from Asia and North Africa too. Medical historian Monica H. Green highlighted how this limits the scope of research to one small population, which could lead to racist misconceptions that Europeans are immunologically superior. The lack of data on the Asian and African populations could reinforce these ideas.

Still, these latest findings shed light on what the long-term impacts of pandemics might be on the evolution of our immune systems. The devastation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the likelihood of future pathogenic outbreaks makes understanding the possibility of such genetic legacies, and their effects on risk of disease, all the more important. As Poinar stated, “Understanding the dynamics that have shaped the human immune system is key to understanding how past pandemics, like the plague, contribute to our susceptibility to disease in modern times.”

Ananya Singh is a Senior Staff Writer at TheSwaddle. She has previously worked as a journalist, researcher and copy editor. Her work explores the intersection of environment, gender and health, with a focus on social and climate justice.

Related

How Unequal Access to Green Space Impacts Health