The Price of Friendship With a ‘Good Man’

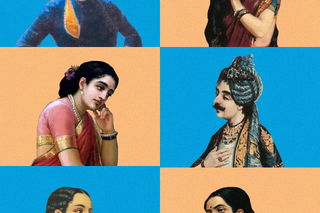

When protests erupted nationwide following the rape and murder of a trainee doctor, a friend shared a pointed dialogue from the film Newton: "You know what your problem is?" someone asks Newton, the titular protagonist, a righteous government clerk grappling with a flawed democracy. "My decency?" he asks. "No," comes the answer. "It’s your arrogance of not being a pervert. You want people to thank you for doing the bare minimum."

This scene is also a telling representation of men who call themselves "good guys," shrugging off their responsibility to confront a system that holds women back. What does it take as a woman to associate and be friends with such men?

In her book, Fight Like A Girl, Clementine Ford wrote about this archetype of “The Super Right-On Male Feminist Ally”: “[He is] totally here for women’s rights and equality and totally wants every woman to know just how here he is for them. He’s so here for them that it upsets him to be associated with those other guys. Instead of turning his Super Right-On attention to schooling those bad boys on their behavior, he thinks it’s more important to get women to acknowledge just how much of an ally he is. And if they refuse to do that, how can he in good conscience continue to support them?”

My friend, Avi*, often declares himself “one of the good ones,” though he claims to dislike saying so. He inhabits the archetype of “The Super Right-On Male Feminist Ally” so comfortably, it shouldn't have been a shock to find his girlfriend crying after he'd shouted at her. But back then, the Avi I knew spoke graciously to everyone. He was a familiar face on campus, his kindness a well-known commodity. The groundskeepers, the cafeteria staff, even the campus cats – all beneficiaries of his generosity. Shouting seemed out of character for him.

It took me a while to realise that there were many other moments like the one with his girlfriend, moments I had dismissed or explained away because it was inconceivable to me that my friend (who was a “good guy”) had meant any harm. Like when he declared he couldn't fathom how women could enjoy one-night stands, and I simply said, “I don't know”; when he carped about women's need to perform their gender, with “I mean, it's just class, not a fashion show”; and when he was furious after a trans woman called him out privately for misgendering her, and I said, “It's okay, you apologized.” While my blind side indulged all that I wouldn't have overlooked in another man, my nonchalance reasserted his goodness in his mind.

In his essay, The Harm That Good Men Do, Bertrand Russell explores the concept of what it means to be a “good” man, contrasting it with the notion of a “bad” man. Russell claws out the general attributes of this man: "The ideally good man … converses in the presence of men only exactly as he would if there were ladies present … and holds the correct opinions on all subjects." Russell adds: "He has a wholesome horror of wrong-doing and realises that it is our painful duty to castigate Sin."

Whenever I’m out with him, Avi’s eyes follow my line of sight, as if we’re both on guard. Like most men in my life, Avi invariably positions me on the pavement side, away from the cars, always switches places with me if a man walks beside me, and never quite grasps why I choose the men I do.

Russell also identifies the good man’s doppelganger, the double he never wants anyone to think he can be: a "bad" man. This man approaches wrongdoing and incorrect thinking with a more critical, scientific attitude, often rejecting traditional moral judgements. Russell’s larger thesis with this juxtaposition is this: a "good" man does not necessarily do more good than a "bad" man. In fact, the distinction between good and bad men might not be about their actual behavior at all.

During the weeks of the protests, I mistakenly sent the Newton stills to Avi, having meant to send them to a female friend. My message read: "dude, i wish i could share this w all the men in our lives lmao." When I realised my mistake, I apologised and tried to change the subject, until he responded: "I thought you were taking a shot at me." After everything I’d been reading that day, I was angry at men, and he was no exception. I didn’t hold back: "hmm, i suppose if you felt called out, that’s worth self-evaluation."

His response was hostile. He had a deluge of things to say to me, from criticizing all the decisions in my personal life to a calculated inventory of his favors – including comforting me after an incident of sexual harassment – all seemingly calibrated to trigger me into hysteria. That was the reaction he wanted, the reaction that would allow him to claim that I was being "emotional," to infantilise me.

It was only when I told him that I was crying that he stopped fighting with me. This was always the case with not only Avi, but most of my male friends. For them, it's an opportunity to exercise their paternalism, to palliate the hurt they created to begin with. By crying, I was conforming to what was expected of me – to cry instead of retaliate to his accusations, to be feminine, whatever that means. In crying, I was accommodating my male friend’s feelings. To him, it was me conceding, choosing his care instead of his ire. I realised he was probably not even reading the news that week. Although if he had been, his response would still have been paternalistic.

“Men are allowed to say things like, ‘I would beat the shit out of any man who was a wife beater,’ or, ‘Those bastard men who rape women are pigs and they ought to be castrated and then shot’,” Ford notes. "Very rarely will you hear these conversations [about feminism and gender equality] being framed in ways that incorporate women as anything other than objects requiring masculine defence."

Ford inadvertently points at the dilemma snaking around the contemporary man: the absence of a "good" model of masculinity. When there's no model to aspire to, it’s easier to go back to square one, as opposed to conceive of a new one. The proliferation of content creators spouting gospels of what a "good" man should look like, and how he must disavow anything touched by the myth of feminism, reflects this quandary. A subsidiary of this media also abundantly perpetuates the worn-out trope of will-they-won’t-they opposite-sex friendships. A woman is either your sister, or like your sister, or she’s a girlfriend. There’s usually no in between. The only "in between," being a platonic friend to a man, comes with hidden costs.

When you’re a woman befriending a man, you become everything a male friend cannot be to that man. Mainstream media mirrors and concretises the reality in which men can only talk about their feelings with other men if there’s an epochal moment in their lives, not just a bad day at work. As a female friend to your guy friend, you are thus slotted into roles you never took on. You have to be a doll he can joke about women with, a makeshift therapist, and a walking encyclopaedia of feminism – expected to answer his every question with the ethnographic authority of lived experience. Since you're not offering sex in return for his friendship, you offer him something else: an alibi. Your sheer existence in his life guarantees him that he’s not like the other men. And when he does something wrong, others will cite you.

A man’s discomfort with a woman’s past, his possessiveness over her history is the same entitlement a man feels over a female friend, her time, and her perceived willingness to teach him how to be a better man. To this man, a woman is not an autonomous being with inherent agency, but an object he can claim he recognizes as having agency, claims as having the willingness to go forward in the feminist movement, even if it requires educating him.

The crux of a male friend's self-proclaimed "goodness" is that it's conditional, dependent on women conforming to his limited worldview. The male friend is comfortable with his female friend as long as she remains within the neat boxes he has created for her – the "cool girl" who doesn't mind his possessiveness and lets him be, the "chill friend" who doesn't challenge his views but acts as a soundboard for his thoughts on feminism. The moment a woman steps outside these boundaries, she becomes a threat to the "good man".

With the 2024 US election looming, this societal conditioning has percolated into the political sphere. Kamala Harris, this year's Democratic presidential candidate, is walking the same tightrope as many women who have befriended men. Unlike her male counterparts, Harris' task this year is not only one of affirmation but also reassurance. She must project both competence and approachability, strength without aggression. To win this election season, Harris must present as a good friend to the archetypal "good" American man. It shouldn't be so hard. After all, she owns a gun. "If somebody breaks into my house, they're getting shot," said Harris in an interview with Oprah, quickly laughing before adding, “Probably should not have said that.” In a Guardian article titled, "Be a man and vote for a woman: Kamala Harris's unlikely edge in America's masculinity election," Carter Sherman writes: “That exchange encapsulated Harris's balancing act.”

If you want to offer a strategic concession to the anxieties of men who feel threatened by female leadership, you just have to downplay your gender. It’s the same way you bite your tongue when a good male friend says something derogatory or problematic. Sometimes, you don’t want to put out the fact that you’re a woman out there, especially when he has seemed to forget.

In her article, Not All Men: A Brief History of Every Dude's Favourite Argument, Jess Zimmerman points out that before “not all men” became a common phrase, other arguments like “what about the men?” and “patriarchy hurts men too” were more prominent. Written in 2014, the article makes a convincing claim that the “not all men” argument reflects a shift in discourse. Initially, men would deny the existence of sexism, then argue that reverse sexism was as bad or worse, and later claim that while sexism is real, they personally are not involved in it. To Zimmerman, the “not all men” argument represents a stage where men acknowledge sexism but assert their personal innocence.

It's a good trick men like Avi play, lulling us into a false sense of security using the salve of bare minimum. They make us believe – and women like Harris reinforce this – that feminism should seek validation from men. In our zeitgeist, one of the few movies ruminating on the prospect of a platonic relationship between a man and a woman is Ae Dil Hai Muskhil, where the woman never returns the male friend’s feelings. When he does decide that he’s happy as long as she’s just a friend in his life, she’s about to die. For women, it seems like there’s always a cost to bear.

So what if America gets its first female president? Will it signify a true shift in the dynamics of gender, or will it merely be a reshuffling of roles within a system that continues to privilege male perspectives and prioritize their comfort? As long as there’s a conflation of genuine friendship with unquestioning validation, the pursuit of true equality, both within our personal relationships and on the national stage, remains a distant dream.

How then should you be a good friend to a woman? Maybe you start by not burdening her with that question. This question needs a space elsewhere, perhaps in the conceptual framework to create a brand-new, sparkling model of masculinity – a framework men should aspire to create. It can, of course, take notes – the resistance is a multilane struggle, after all. Just don’t jaywalk, bro.

* Names changed to maintain anonymity.

Diya Isha is an editor, writer, and book critic based in New Delhi.

Related

Pop Culture Is in its Feudal Era