The World Is Turning to AI Weapons to Reduce War Casualties. What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

Artificial intelligence is a volatile, developing technology riddled with errors, bias, and almost no legal regulation.

AI is a volatile, developing technology riddled with errors, bias, and almost no legal regulation. What could go wrong?

A U.S. government thinktank — the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence (NSCAI) — recently published a draft report stating that it is necessary to continue developing AI-based autonomous weapons systems to defend the U.S. against future threats.

This conclusion is unsurprising, considering the U.S. is the world’s largest military power with no interest in giving up its position. But another reason the NSCAI’s Vice Chairman Robert Work gave to pursue the development of AI weaponry is that artificial intelligence will make fewer mistakes in battle, leading to reduced casualties caused by target misidentification.

Work adds, “It is a moral imperative to at least pursue this hypothesis.”

While all manner of morals and ethics are at odds with the choice to manufacture killer robots for war, this particular statement is also controversial because it uses human rights as an excuse to marry weaponry to AI — a volatile, developing technological field riddled with errors, bias, and almost no legal regulation.

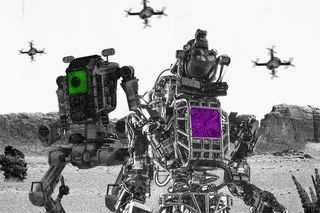

The AI weapons in question are called Lethal Autonomous Weapons (LAWs). No fully functional LAWs have been created yet, but technology exists that can enable a weapon to become partially autonomous. The difference between the semi-autonomous drones that exist now and fully AI-powered LAWs is that the latter will not need human assistance to know when or where to shoot. According to the NSCAI report, AI technology can function under the terms of the International Humanitarian Law if it can distinguish between enemies and civilians, weigh the proportion of lives lost with military advantage, and have a human being responsible for its development, testing, use, and behavior.

For the military, this is a cheaper and more ethical means to wage war, because it protects soldiers’ lives on the home turf and ensures minimum violence inflicted among civilians. Artificial intelligence cannot feel sadism, rage, or hate, either, which cuts out motives for a significant number of war crimes. On paper, they are perfect, efficient machines of war.

Related on The Swaddle:

The Tech Industry’s Sexism, Racism Is Making Artificial Intelligence Less Intelligent

Except, robots and artificial intelligence are coded and built by human beings who embody a significant number of such vices. Researchers and journalists have uncovered several instances in which artificial intelligence shows unconscious bias — like AI that makes legal judgments without controlling for racial inequalities in the legal system. There are also reports of users inserting malicious bias into AI, with the most prominent example being Tay, the supposedly neutral Microsoft chatbot that morphed into a hate-spewing fascist after internet users intentionally taught the AI hate-speech. If such bias and hate is possible on a much smaller scale, AI-enabled lethal autonomous weapons can easily be coded into a highly efficient ethnic-cleansing tool.

Even in an ideal environment, minus any bias, the ability to create AI with ethical and legal mastery is almost impossible, according to computer scientist Noel Sharkey, due to the sheer variety of situations that can arise in war. Sharkey argues that associating legality or ethics with a machine is merely a means to encourage trust in the machine. He writes that such words “act as linguistic Trojan horses that smuggle in a rich interconnected web of human concepts that are not part of a computer system or how it operates. Once the reader has accepted a seemingly innocent Trojan term …. it opens the gate to other meanings associated with the natural language use of the term.” What Sharkey means is that artificial intelligence is a highly sophisticated piece of software; attributing human capabilities like ethics or kindness is a disingenuous way to depict artificial intelligence. Even the most sentient AI is its own unique ecosystem; it does not function with human morals.

An example of this shows up in U.S. Army Ranger Paul Scharre’s book, Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War. While he was in Afghanistan, Scharre and his unit went out scouting and their presence was discovered by the Taliban. The spy who reported their presence was a 6-year-old girl pretending to herd her goats. Scharre states that even though it was legal to kill a Taliban informant, none of the soldiers in his unit even considered killing the child. But a robot would have no such filter because, as Scharre writes, “the laws of war don’t set an age for combatants.” Scharre further writes that robots may be able to follow the law and stay unbiased, but “… what’s legal and what’s right aren’t always the same.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Autonomous weaponry also poses dangers like catastrophic malfunctions that result from the competitiveness of weapons technology. In response to the NSCAI’s report, Mary Wareham, coordinator of the eight-year campaign, Stop Killer Robots, told Reuters that the commission’s “focus on the need to compete with similar investments made by China and Russia … only serves to encourage arms races.” Including AI into an arms race rather than keeping AI research collaborative and in the public domain creates more room for error and dubious ethical practices. Even then, countries like the U.S. may justify their secretive development by pointing to comparatively worse threats from authoritarian or volatile regimes like Iraq, North Korea, or Pakistan. But, the U.S. itself was a volatile regime until last year, helmed by a xenophobe who wrote racist practices into law, proving that no country has the moral authority to be entrusted with the responsibility of artificially intelligent weapons without checks and balances.

The only way to prevent an AI arms race is if large military powers join the list of 30 countries and the U.N. in enacting a moratorium on the development of ‘killer robots,’ but large military powers like the U.S. continue to promote limitations on using AI weapons rather than support outright bans. Plus, most countries remain cautious rather than proactive about crafting AI regulation; the U.S., in particular, has only put forth a draft law in 2019 titled “Guidance for Regulation of Artificial Intelligence Applications.” This means the majority of AI-regulation responsibility falls upon private companies creating the AI, which have a greater impetus for profit than public service. Even when AI laws were to be put in place, they would protect national interests over the world’s interests.

Still, there’s hope. A February 2021 survey states that more than 75% of people across 28 nations firmly oppose AI weapons, which means that the public can push politicians to change the status quo. And several scientists and technology workers from prominent companies like Google and Microsoft have openly refused to work with the military as an act of dissent, delaying the development of such weaponry. And, like biological weapons, as AI-powered weapons are developed, they will become more and more inexpensive, making them accessible enough to cause large-scale damage — and thus to ban. This accessibility led to the ban of biological warfare, and scientists predict the same will eventually happen for AI warfare, too. Yet, as technology proceeds to develop at rapid speeds in comparison to the ambling pace of policy that can restrict it, the possibility of war being fought by systems that do not understand war well enough to mitigate damage only nears.

Aditi Murti is a culture writer at The Swaddle. Previously, she worked as a freelance journalist focused on gender and cities. Find her on social media @aditimurti.

Related

Ministry of Home Affairs Pilots Program Asking Volunteers to Report Cybercrime, Anti‑National Activities