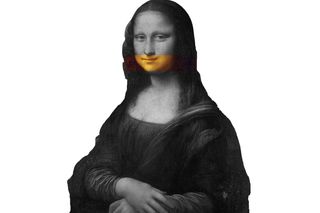

There Are Dozens of Smiles, But Only One Conveys Happiness

If you’ve ever smiled at someone while absolutely hating them, you’ve smiled the ‘contempt smile.’

A smile is a ubiquitous facial expression, one that generally signifies a pleasant state of mind and one we generally associate with happiness. But researchers have studied this facial phenomenon quite deeply, and it turns out most kinds of smiles our facial muscles are capable of can signal myriad different emotions — states of mind nowhere close to happy, good or pleasant.

“Some evolved to signal that we’re cooperative and non-threatening; others have evolved to let people know, without aggression, that we are superior to them in this present interaction,” Paula Niedenthal, a psychologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told the BBC.

A smile occurs when facial muscles get a signal from the brain — its left anterior temporal region, to be exact; it sends signals to the facial expression muscle (zygomatic major) in the cheeks to tug the corners of the lips upward and instructs the orbicularis oculi, present around the eye socket, to contract which squeezes the ends of the eyes into a crinkle, according to Psychological Science. The combination of the upturned lips and the eye crinkle form the Duchenne smile — a kind of smile researchers almost universally agree signals a “true” indicator of enjoyment and joy. (Researchers have, however, documented the Duchenne smile when someone is tickled, wherein the participants later expressed no joy in the process.) Named after French anatomist Guillaume Duchenne, the smile is supposed to signify the “sweet emotions of the soul.” Duchenne had said at the time if the eyes don’t crinkle, it “unmasks a false friend,” according to Psychological Science.

Related on The Swaddle:

Loneliness Might Impair Our Ability to Smile Spontaneously

What Duchenne considered fake smiles have since been deeply explored — Paul Ekman, a psychologist at the University of California, documented seventeen smiles, other than the Duchenne smile, in his book Telling Lies. He found people often utilize the “smile mask,” an emotional mask in the form of a smile that is used to conceal an underlying negative feeling, such as fear, anger or disgust. “The smile mask is often selected because many lies require some variation or signal of happiness in order to successfully pull off deceit. Another reason the smile is used as a mask so often is because smiling is part of many standard greetings and is required to be shown frequently to signal politeness throughout most exchanges,” reads an excerpt from Ekman’s book.

Ekman writes that in social interactions, people rarely care to unmask what’s underneath a smile, which is why many people get away with employing different renditions of a smile without having to spill what it is they’re really feeling. And for the other person receiving the smile, Ekman writes, usually “all that is expected is a pretense of amiability and pleasantness.”

Ekman separates false smiles into two categories — the “phony smile,” which is an attempt to “appear as if positive feelings are felt,” and a “masking smile,” in which “strong negative emotion is felt and an attempt is made to conceal those feelings by appearing to feel positive.” Phony smiles are more believable than masking ones, as the former doesn’t have a conflicting negative emotion that impedes the person’s ability to fake a smile, according to Ekman.

Phony smiles can be identified by recognizing subtle muscle movements, Ekman writes — the orbicularis oculi, or the eye-crinkling muscle, is often absent from the phony smile; but it could be present in the masking smile as exhibiting emotions of distress or anger can also engage the orbicularis oculi. Another marker is that a phony smile will often be asymmetrical, “generally stronger on the left side of the face if the person is right-handed.” A 1981 study by Ekman found that asymmetrical smiles were more abundant in children who were asked to smile on request than those who smiled spontaneously. A third marker, this one purely based on anecdotal self-reportage, is that a phony smile often comes too early or too late in the interaction, according to Ekman. The duration of a smile, Ekman suggests, can also be a factor when trying to distinguish between an earnest and a phony smile — the former is much shorter in duration, between two-thirds of a second and four seconds, while the latter lasts for a deliberately long time.

Masking smiles, by which people mask negative emotions, are more difficult to identify. Ekman writes that a person masking an underlying emotion with a smile will often betray their original emotion in the upper half of their face, more than their lower half — “leakage of negative emotions may still be evident in … the upper eyelids, eyebrows and forehead.” If the underlying emotion is strong, some movements in the lower face also might betray the fake smile, such as “the lips may be pressed, the lower lip pushed up, or the tightening of both lip corners.” These might show that an emotion is being masked, but won’t betray which one, Ekman writes. This underlying emotion doesn’t necessarily have to be a negative one — Ekman identified a “dampened smile,” which signals that a person is trying to hide the intensity of the positive emotion that led them to smile, which can manifest in ways akin to a masking smile.

He identified another kind of smile — “the miserable smile” — in which “a person does not experience any positive emotion and does not attempt to appear as if positive emotion is felt. Instead, the miserable smile acknowledges feeling unhappy, making clear to the self and to others that the response to the misery is, at least for the moment, contained … that tears and screams will not occur. If the misery is fear, no escape will be attempted; if it is anger, no attack will be made.” Ekman suggests miserable smiles will be clearly “super-imposed on a negative-emotion expression, or follow a negative-emotion expression.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Out of Thousands, Only 35 Facial Expressions May Be Universal Across Cultures

Ekman, along with fellow psychologist Wallace Friesen and Maureen O’Sullivan, also identified smiles people gave when they were lying — in 1988, they published a paper in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology that detailed an experiment, wherein they asked nurses to watch a gruesome video and then lie about it afterward and say it was a pleasant one. They observed that the nurses gave fewer Duchenne smiles; “The deceitful grins were betrayed by either a raised upper lip, revealing a hint of disgust, or lowered lip corners, displaying a trace of sadness.”

Other smiles researchers have identified over the years include the embarrassed smile, which “reveals itself through an averted gaze, a facial touch, and a tilt of the head down and to the left,” according to Psychological Science. The “qualifier smile aims to take the edge off bad news,” the BBC reported, and it “begins abruptly, raising the lower lip slightly, and is occasionally accompanied by a slightly downwards and sideways tilt of the head.” The BBC report further adds that the qualifier smile can be deployed on various occasions — to reassure someone you’re still listening, often accompanied by “mm-hmm noises,” or to show agreement. Then, there’s the “contempt smile,” a signature of which is a real smile but tightened at the corners of the lips; the smile of “malicious joy,” often found in pop culture in the form of a creepy grin (think: The Joker); and the “flirtatious smile,” in which the person smiles, glances sideways quickly and ends with an “embarrassed smile,” the BBC reports.

Depending on the context, length, and structure of the smile, and the smile’s juxtaposition against other facial expressions and body language, researchers have found a smile can mean a million different things. The more we understand smiles, the more we become attuned to other’s emotions, the easier it gets for us to identify them and offer support if needed. And if nothing else, the more fun it is to fuck with other people. 🙂

Rajvi Desai is The Swaddle's Culture Editor. After graduating from NYU as a Journalism and Politics major, she covered breaking news and politics in New York City, and dabbled in design and entertainment journalism. Back in the homeland, she's interested in tackling beauty, sports, politics and human rights in her gender-focused writing, while also co-managing The Swaddle Team's podcast, Respectfully Disagree.

Related

Explaining the Vocabulary of the Gender Spectrum