Transgender Kids’ Brains Reflect Their Gender Identity in Structure and Function

Meaning that transgender kids aren’t ‘too young to know.’

For anyone who hasn’t lived it, understanding the experience of a transgender kid can be difficult. Many parents might wonder how a child even knows they’re transgender. Aren’t they too young to experience, or identify with, a gender different to their biological sex?

No, they aren’t. By around age 4 or 5, kids have a fairly rigid view of gender identity, unless raised to have a more fluid view. By age 10, they’ve imbibed stereotypes that supposedly define their gender. And by adolescence, if not earlier, transgender kids’ brain activity and structure more closely resembles the typical activation patterns associated with the sex of their gender identity, according to findings to be presented at the European Society of Endocrinology annual meeting in Barcelona.

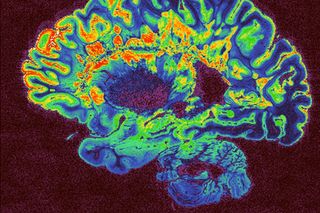

The new study, led Dr. Julie Bakker from the University of Liège, Belgium, and her colleagues from the Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria at the VU University Medical Center, the Netherlands, included both adolescent boys and girls who had experienced distress from identifying with a gender other than their biological sex (a state known as gender dysphoria). Through MRI scans, the team assessed brain activation patterns in response to a pheromone known to produce gender-specific activity.

They found the pattern of brain activation in both transgender adolescent boys and girls more closely resembled that of their gender identity among non-transgender boys and girls. In addition, adolescent transgender girls with gender distress showed a male-typical brain activation pattern during a visual/spatial memory exercise. Finally, some brain structural changes were detected that were also more similar, but not identical, to those typical of the desired gender of boys and girls distressed about their gender.

“Although more research is needed, we now have evidence that sexual differentiation of the brain differs in young people with [gender distress], as they show functional brain characteristics that are typical of their desired gender,” Bakker says.

Bakker hopes this finding could help improve the quality of life of and support available to young transgender people and their families. Gender identity is an essential part of psychological health, and if related distress is unaddressed, it can lead to serious psychological issues. Current strategies for addressing gender distress in younger people involve psychotherapy, or delaying puberty with hormones, so that decisions on transgender therapy can be made at an older age.

Bakker plans next to investigate the role of hormones during puberty play on brain development and transgender differences, to help guide and improve future diagnosis and therapy for gender-distressed adolescents.

“We will then be better equipped to support these young people, instead of just sending them to a psychiatrist and hoping that their distress will disappear spontaneously,” she says.

Related

Intermittent Fasting Diets May Contribute To Diabetes Risk