‘Tuca and Bertie’ Showcases a Raw, Messy View Into the Female Brain

The surreal comedy illustrates the strange, dark things women think and do.

While talking about how Netflix’s Tuca and Bertie was created, Lisa Hanawalt mentions her love for characters who are devoid of shame and fear. In an interview with Vulture, she said, “I was watching a nature documentary to relax, and I saw this footage of a toucan reaching into other birds’ nests and stealing their eggs and eating them. I was like, ‘Oh my God, that’s me. I love eating all the eggs. I’m so greedy with food. This character is my id. I’m going to create Tuca.'”

Her first animated show post a stint at Bojack Horseman, Tuca and Bertie is made up of sweet, surreal illustrations of modern day female bonding. In creating this show, Hanawalt finds herself in a scarce group of women who have created animated shows aimed at adults. Considering ‘Adult Swim’ executive Mike Lazzo said, “When you have women in the writers room, you don’t get comedy, you get conflict,” the scarcity is both tedious and unsurprising. Therefore, Tuca and Bertie’s massive success is extremely important for the future of animated comedy, because it is unbridled, unspoken permission for scores of young women to pick up their pens, dream up the wildest things their conflict-addled brains can conjure and put it out for the world to see. For Tuca and Bertie is a whole new visual world, both gross and fascinating, that pushes boundaries on what’s traditionally enjoyed as adult-oriented animated comedy.

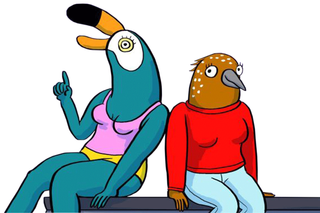

Tuca the toucan, played by Tiffany Haddish, is a confident booty-shorts connoisseur who is absolutely id. Her sneakers are in the fridge; she’s hooked up with the resident apartment creep more than once; she survives on her rich auntie’s handouts when her gig-to-gig work life often takes a back seat. Her best friend Bertie, the songthrush, who is played by Ali Wong, leans more towards the superego. She’s a baker, painfully neat and secretly crushing on other men while perpetually anxious that her relationship with easygoing boyfriend Speckle might fall apart. Tuca and Bertie, pushed as a fresh take on the outgoing-and-introvert friends trope, creates two lush, filled out, extremely confused best friends coping with the hodgepodge of present problems and past traumas that is life in your 30s. They embody the messiness of womanhood, in the most honest, out-there possible way.

In fact, the very city of BirdTown, in which Tuca and Bertie is based, comes across as vividly feminine. Buildings have wobbly tits, plants are moody, vaping young women in crop tops, mean mirrors tell you you’re ugly and large snake trains curve about the city, ferrying BirdTown dwellers around. It is in this surreal universe that we meet Tuca and Bertie, both in their 30s, on the cusp of drastic adult boringness like house hunting, career upgrades and long-term relationships.

There’s a certain kind of messy the current audience has come to expect from women in films and TV. Ever since Gone Girl dropped the Amy Dunne-bomb upon eager female consumers, cool girls became pariahs overnight. The new heroine falls on the darker side of grey, making big mistakes and bracing for the reckonings that come with them. Rather than braving a few paltry speed bumps, modern day conflict is a steep ditch the heroine must climb out of — that too, rarely unhurt, with vulnerable, oozing wounds aired out for the world to see. Dark comedies like Fleabag, where the titular protagonist must cope with the aftermath of committing a socially unforgivable act, are roaring successes while rom-com confections like I Feel Pretty, which barely skims body positivity, fail to endear themselves to viewers as well.

When it comes to conflict, Tuca and Bertie keeps the vulnerability, but eschews the bleak, dark comedy of its peers for a more hopeful, optimistic outlook. For example, Bertie’s mind grapples with the right definition of abuse, often confusing fear for attraction and in the process, letting down others for whom certain acts were clear violations. Her agony at dealing with men who cross boundaries is gently eased into, with the final episode channeling the beginning of her healing process rather than tying it up into a happy-ending knot. Whereas Tuca’s lack of responsibility is showcased as a recurring foible — she deals with both the guilt of being unable to rely on herself and her paralytic fear of changing into someone who sinks into the same boring routine as everyone else. While on a date, she behaves erratically and flashes her partner because her entire experience with partnerships and dating involve being blackout drunk, and a mere object.

What’s pleasantly surprising is that Tuca and Bertie, a sweet, silly gag fest, portrays raw mental friction, discomfort and the almost familial reliance adults have on close friends — all without a single insensitive moment. The show embraces both messy, gross behavior, and nervous prudery wholly. While Tuca plays sexual role playing games RPGs on the Internet, Bertie watches ‘The Nests of Netherfield’, an exaggerated Austen-esque show to get in the mood. Similarly, while Tuca’s hands get sweaty while holding her date’s, Bertie slips into a bathroom in the bakery she moonlights at, and masturbates while thinking about the authoritative chef she trains under.

Perhaps Lisa Hanawalt’s insistence on creating something drastically different from her time as production designer at Bojack Horseman helped. While Bojack is often representative of the worst bits of us, Tuca and Bertie feel like parts of any regular woman’s brain chatter. In fact, Hanawalt is so proud of her characters’ warm, raunchy womanliness that she keeps a sign she made for the 2019 Los Angeles Women’s Marchat the ShadowMachine animation studios, where “Tuca and Bertie” was made: It features Tuca’s legs spread wide, revealing a cluster of bird pubic hair and the words, “NASTY AND PROUD.”

In a sea of adult comedies aimed at man children, Tuca and Bertie sticks out like a sore thumb. The fact that such groundbreaking, universally loved work emerges from one of the few rare woman show-runners in the animated show business makes it clear that women are more than competent at drawing out the intricate details of womanhood, figuratively and literally. Tuca and Bertie’s messiness is a tribute to much policed and overwritten girl brains and the nasty, rotten and absolutely delightful ways in which they see the world.

Aditi Murti is a culture writer at The Swaddle. Previously, she worked as a freelance journalist focused on gender and cities. Find her on social media @aditimurti.

Related

Thank You, Phoebe Waller‑Bridge, for Writing Real Reel Women