UN Grants Consultative Status to Dalit Rights Group After 15 Years

A Dalit rights group’s status marks longest time an NGO’s application for consultative status was blocked at the UN ECOSOC.

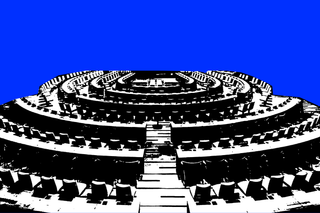

The International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN), a Coppenhagen-based international group working to highlight caste discrimination and advocate for Dalit Rights at a global level, was on Wednesday granted consultative status by the United Nations (UN) Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). IDSN was among eight other organizations which will now have access to the UN and can therefore offer their inputs in support of the UN’s work protecting and promoting human rights.

Notably, the IDSN’s request for consultative status was approved more than 15 years after their first application, marking a record of the longest deferment of an application made by any organization at the UN. In their detailed report on the deferral, the IDSN states that they first submitted their application seeking consultative status to the ECOSOC’s Committee on NGOs in May 2007. “Since then, the application has been deferred at the following regular and resumed sessions of the Committee. During this period IDSN has received 101 written questions, to which IDSN has always responded in due time.” The IDSN further explains, “Many of the questions have contained similar content, or have already been responded to in the application or previous replies. Often the new sets of questions have been submitted to the organization so late during sessions that the Committee has not had time to review the answers at the same session. The application has then been deferred to the next session along with a large number of other deferred applications; postponing a final decision on the application.”

Interestingly, as the International Service for Human Rights notes, most of these repetitive and deliberately late questions came from India. This hints at India’s unease with the discussion of caste discrimination and Dalit rights on a global level. In fact, India has had a long history of objecting to any discussion of casteism or the state of its marginalized castes in international fora.

Dalit scholar Suraj Yengde notes India’s opposition to discussing caste right from its independence. On the one hand, the Indian government “undertook the UN-level fight against apartheid in South Africa and even co-sponsored resolutions imposing sanctions on South Africa.” On the other, however, it “did not take up India’s caste issue on any international forum.”

In March 2016, a few months Dalit scholar Rohith Vemula died by suicide in what’s come to be recognized as an institutional death, the UN Human Rights Council published a report on the state of Dalits in the country. However, the Indian Government strongly objected to the contents of the document. India raised questions on the seriousness of the report’s work, and a government official told The Wire, “it does not seem that the report was done based on any field studies based on country visits. It seemed more like a research compilation.”

India thus remains deeply reticent about discussing Dalit rights as human rights. It goes against the grain of previous trends, where the country projected itself as a land of peace and harmony. Moreover, it also reflects the country’s unwillingness to afford power and privileges to Dalits as equals — even after thousands of years of unbridled discrimination.

Related on TheSwaddle:

Hindutva Extremists Are Attacking Anti‑Caste Music in Punjab. The Hate Is Not New.

Recent conversations about casteism in other countries reflect the discomfort with the growing acknowledgment of casteism as a human rights violation. On the same day that IDSN was finally recognized by the UN ECOSOC, Brown University became the first Ivy League educational institution to ban caste discrimination across its campus. In the last few years, some universities and colleges in the US have passed legislation to identify caste as a specific basis of discrimination and to work to prohibit such discrimination. This spate of protection, however, has been strongly opposed by upper-caste diaspora groups in the US as being discriminatory and “anti-Hindu.”

At the forefront of this opposition is the Hindu American Foundation (HAF) — a group associated with the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, a Hindu nationalist organization founded by MS Golwalkar from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). HAF argued that adding caste as a protected category in anti-discrimination policies will endanger the lives of Hindus on university campuses, and that caste in itself was a “stereotype” pushed against India and Hindus only during the British Raj. The delay in granting consultative status to a Dalit group at the UN then hinders the space for countering such a narrative.

Although progress has been slow, the last few years have shown how conversations about casteism have become more common in the United States. In 2020, the state of California sued the technology company Cisco and its senior employees for practicing caste discrimination against a Dalit employee. The lawsuit brought to the fore the hidden casteism in America that has persisted for decades, imported by immigrating Indians over the years. “Caste may have traveled from India and penetrated American workplaces, colleges, and communities, like tea from a tea bag, somehow allowing a millennia-old system of discrimination to remain intact in Massachusetts as much as it has in Maharashtra,” writes journalist Vidya Krishnan while describing her experience witnessing caste being practiced by members of the Indian diaspora.

Earlier this year, during Dalit History Month, Thenimozhi Soundararajan, founder of Equality Labs, an American civil-rights organization focussing on caste, was invited — and then uninvited — by Google, an organization headed by an Indian, to deliver a talk about caste discrimination at their headquarters. According to reports, dominant caste employees protested against the talk alleging they’ll face discrimination if the talk was held. Tanuja Gupta, an employee at Google who chose to stand by Soundararajan during the entire episode, faced retaliation from Google in the form of an HR investigation and other punitive measures, which eventually forced her to resign. This incident and the larger opposition to identifying caste discrimination on the grounds of it being “anti-Hindu” reflects the upper-caste Indian diaspora community’s uneasiness with caste discrimination being recognized on the global level.

These oppositions beg the question of whether caste discrimination is so intrinsic to the Indian or Hindu identity that even acknowledging it threatens the existence of those continuing to practice it. International recognition of caste discrimination and Dalit groups — especially at the UN — stands to change the global understanding of the hierarchies within Hinduism. This in turn disrupts how the upper caste diaspora erased casteism abroad.

Amlan Sarkar is a staff writer at TheSwaddle. He writes about the intersection between pop culture and politics. You can reach him on Instagram @amlansarkr.

Related

Feminists in South Korea Are Protesting a Wave of Anti‑Feminism