UN Official Resigns Over UN’s Failure to Address Genocide in Palestine

Critiqued often for being rooted in Western ideals of liberalism, is the international human rights framework inadequate?

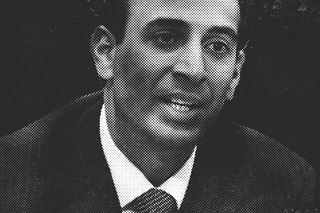

On 28th October, Director of the NY Office of the UN High Commissioner of Human Rights, Craig Mokhiber resigned. In his resignation letter, he stated this was in protest against the United Nation’s “failure” to prevent what he calls a “textbook case of genocide" against Palestinian civilians in Gaza.

Mokhiber, a lawyer who specializes in international human rights law, has worked for the UN since 1992. Expressing his deep concern, he stated, "Once again, we are witnessing a genocide unfolding before our eyes, and the organization we serve appears powerless to stop it." Published on social media, his official resignation letter pointedly implicates the United States, the United Kingdom, and much of Europe, asserting that they are "wholly complicit in the horrific assault." This stark indictment underscores Mokhiber's frustration with what he deemed as a lack of effective action by the UN in the face of a grave humanitarian crisis. “We are failing again,” his letter iterates.

Mokhiber's four-page resignation letter spoke of the “decades of distraction by the illusory and largely disingenuous promises of Oslo [Accords],” which he holds accountable for having “diverted the Organization from its core duty to defend international law, human rights and the charter itself.” His critical reflection over the UN’s shortcomings – calling out various stakeholders such as governments, national leaders, media, and corporate entities – occasions a deeper inquiry into the universalization of human rights, which has often been criticized for adopting a one-size-fits-all approach.

Scholarly accounts have highlighted how the intellectual foundation of international human rights law, due to it being bent towards individual human rights over group rights, has played an active role in the dispossession and disenfranchisement of colonized peoples. Sujith Xavier, a decolonial scholar argues, “Law and its various institutions are the means by which colonial, imperial and settler colonial programs and policies continue to be reinforced and sustained.” Even if organized within the liberal language of “sovereignty and self-rule,” scholars argue that human rights standards as we know them today were founded in sites of Western knowledge production, which overcast its influence even before inception.

A major enduring critique of the UN’s human rights approach has been the privileging of civil and political rights – over economic and cultural rights. Historically speaking, with the Western Bloc’s victory after the second world war, civil and political rights came to supersede economic, social and cultural rights due to the neoliberal logic of the former requiring less investment as opposed to the latter – marking the cementing of an individualistic human rights framework, globally.

Moreover, the language of freedom; of life, liberty, and speech – which were the basis of the American Declaration of Independence – became the template against which all regimes have been judged since the later half of the 20th century. This has caused scholars from the Global South, Indigenous and Muslim communities to frequently rehash the “flawed universalism” of human rights.

During the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) drafting debates in 1948, Saudi Arabia's representative, Jamil Baroody, challenged the Western bias of the doctrine: “The authors of the draft [UDHR] had, for the most part, taken into consideration only the standards recognized by western civilization and had ignored more ancient civilizations which were past the experimental stage … It was not for the [drafting] Committee to proclaim the superiority of one civilization over all others or to establish uniform standards for all the countries in the world.”

Professor of Islamic Studies, Abdulaziz Sachedina, who has attempted to articulate the concerns of the Muslim world over human rights, believes that the West’s individualistic approach lies at the root of the problem. The overriding emphasis on the autonomy of the individual with an independent moral standard that transcends religious and cultural differences to claim rights – without considering the bonds of reciprocity – runs contrary to the Islamic tradition’s emphasis on the community and relational aspects of human existence. Such an approach disconnects the international human rights approach from local historical contexts.

Muslim leaders and Islamic advocates thus strongly claim that Islam protects human rights, utilizing an interpretation of the international laws based on Islamic laws. In turn, the West – in its misgivings over the non-respect of a codified human rights law – perceives this as a dilution of the international standards and uses it to justify their hostility towards the Islamic states. Since the 1940s, not much has changed for the UN and its bodies, despite the global landscape shifts and the desire for reframing how we think about the relationship between political identities and power.

Mokhiber highlights how the Western corporate media has been broadcasting “state-adjacent’’ propaganda for war, while social media conglomerates have been shadow banning and erasing the voices of defenders of human rights. Here, it is essential to understand that the study of racial and ethnic minorities must be the study of oppression and resistance, as sociologists studying human rights have pointed out. To that effect, the very definition of the term “minority” refers specifically to a location absent of social power, says sociologist James M. Thomas.

Further, Mokhiber's statement – "the UN itself carries the original sin of facilitating dispossession" – reveals the flawed logic of neoliberal imperialism carried out through the UN’s humanitarian interventions. Mokhiber writes, “the (US-scripted) deference to ‘agreements between the parties themselves’ (in place of international law) was always a transparent sleight-of-hand, designed to reinforce the power of Israel over the rights of the occupied and dispossessed Palestinians.” Consent of the masses is often seen as a key tool for an authoritarian regime, legitimizing its actions. However, when an expansionist regime no longer relies on consent, people are left with no choice but to endure the hardships imposed by the Western regime if they want political or economic power, as is happening with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. “In some sense, the framers [UDHR] were promising human rights to everyone, except the Palestinian people,” Mokhiber reflects. In this, the UN’s foundation of a “rights-based paradigm” can be arguably deemed obsolete, due to its inability to fundamentally take a moral position for documenting and addressing societal ills and concerns of violations.

The Human Rights Council, established in 2006, tasked with promoting and protecting human rights globally has “repeatedly failed, especially in responding to human rights emergencies,” adds Mokhiber.

“Critical accounts identify a tendency to overemphasize human rights violations in the Global South, which tends to construct a non-Western ‘other’ that needs to be saved by Western states. Thereby, the human rights regime creates a dichotomy between the Western embracement and the non-Western violation of human rights. This dichotomy neglects human rights violations in Western states and disregards the complicity of the latter with the former,” notes a 2019 article in the Journal of International Political Theory, highlighting how the human rights framework reinforces an almost racist dichotomy. “What is more, critical accounts emphasize that Western states use the frame of human rights to legitimize their interventions in other states.” Critics also assert that the “bearer” of human rights is Western, White, male, individual, and liberal. Accordingly, the human rights regime neglects the needs and living conditions of others as well as the values of communities and groups.

In the current political global climate, the term “genocide” itself has been subjected to scrutiny by the corporate media and global leaders, despite the incoming images and reports from ground zero. The West’s practice of “color-blind racism” – the overarching contemporary logic behind its ethnic and racial stratification – therefore persists. The Western tendency to simplify and stereotype the "other" into a political category has manufactured an ideological framework, wherein political agency is portrayed as a form of resentment – trivializing political engagement to a mere reactionary and emotional response, omitting the historical complexity of motivations that drive any acts of resistance.

Naina is a sociology graduate of the Delhi School of Economics. She presently works as a writer focusing on queer theory, culture, media semantics, and women's health.

Related

.jpg?rect=0,80,1280,1280&w=320&h=320&fit=min&auto=format)

We Are Officially in the Epoch of Disinformation