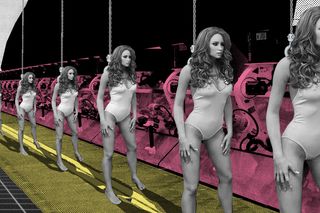

We Will Soon Have Sentient Sex Robots. Will They Be Able To Consent?

Meaningful consent is possible only if robots achieve independent decision-making skills, which many futurists believe is only a few decades away.

This is the second article in a two-part series about how humanoid robots may change how human society understands sex and sexuality.

The world is only now beginning to grapple with the many nuances of sexual consent on a large scale due to feminist movements like #MeToo. But, with futurists predicting meaningful relationships with sentient robots within a matter of decades, we might have to quickly progress to even more nuanced discussions around consent.

The $30 billion sex industry, obviously for-profit, is geared to creating more hyper-realistic, intelligent robot companions for their top audience — cis-straight men — in the years to come. . As robots get more sophisticated AI, they will gain independent decision-making skills that will give them a specific legal status as electronic persons, according to a 2016 draft resolution put forth by the European Union Parliament. The draft said, “The more autonomous robots are, the less they can be considered simple tools in the hands of other actors … As a consequence, it becomes more and more urgent to address the fundamental question of whether robots should possess a legal status.” When included as citizens and part of a civil society — like Sophia the robot, who received citizenship from Saudi Arabia in 2017 — such electronic persons or robots cannot be used for non-consensual sex without raising ethical, moral, and legal questions.

Related on The Swaddle:

Consent Is More Than Just a Yes to Sex, It’s an Enthusiastic Yes

In Artificial Intelligence and Law, ethicists Lily Frank and Sven Nyholm write, “The legal community should make it very clear that any member of the legal community who enjoys the status of personhood needs to give his, her, their, or its consent before any sexual acts are performed on them. It cannot be that the legal community does anything that can be construed as condoning what is sometimes called ‘rape-culture,’ i.e., a mindset by which non-consensual sex is normalized or otherwise implicitly or explicitly approved of largely as a result sexist attitudes, institutions, and patterns of behavior.”

Sex robots that can give and withdraw consent already exist, but the models of consent utilized are a work-in-progress. This is mainly because, as of now, sex robots can only simulate consent, rather than actively give consent. It is imperative to note that meaningful consent is possible only if robots achieve independent decision-making skills — a possibility many policymakers and researchers believe is only a few decades away. A California-based cult group UNICULT started a fundraiser for a sex robot brothel that allows customers to only have intercourse with robots after they’d used a relevant app to converse with them enough. The robots would always consent to sex after the points were earned, so the consent model in question only put forth an illusion of choice. Another sex-robot creator named Sergi Santos made Samantha, a sex-robot who can say “no” and activate “dummy mode,” becoming lifeless if she is touched aggressively, bored, or tired. The problem here is that this doesn’t stop the person who owns the robot from raping the robot.

This is why philosopher Robert Sparrow argues against designing robots with the ability to consent, as it allows the fulfilment of a rape fantasy if consent is denied. In the International Journal of Social Robotics, Sparrow writes, “Even when the intention is not to facilitate rape, the design of robots that can explicitly refuse consent is problematic due to the likelihood that some users will experiment with raping them.” He explains, “[I]t will not be possible to rape robots unless the designers of robots make certain design choices.”

But the matter is not as simplistic as that, as Sparrow notes, “If, on the other hand, sex with such robots is never a representation of rape—and especially if that’s because the robots have been designed so as always to consent to sex—then the design of sex robots may well be unethical for what it expresses about the sexuality of women.” And this is the main reason the question of consent is an important one to consider going forward.

Related on The Swaddle:

It’s Time We Start Negotiating Non‑Sexual Consent, As Well

Almost all sex robots are currently modeled on a human woman’s mannerisms and behaviors. This creates wider implications — mainly that non-consensual sex with robots might also lead to the dehumanization of human women. This is similar to feminist critique of attitudes towards pornography and sex workers. Anthropology and robotics expert Kathleen Richardson bring up the unequal power dynamic and lack of respect that customers show sex workers to predict the future of sex robots. “Technology is not neutral,” Richardson tells the Washington Post. “It’s informed by class, race and gender.” Richardson uses the frequent associations between sex robots and prostitution to show that sex robots will be utilized as receptacles, which, in a vicious circle, will inform attitudes towards women.

A more contemporary example of how Richardson’s theory plays out is the conversation about the redistribution of sex. A theory first espoused by Robin Hanson and later championed by violent involuntary celibate (incel) fringe forums, the redistribution of sex involves the state controlling women’s bodies and the men they have access to, in order to make sure everyone has access to consensual sex. If some women don’t consent, sex workers and sex robots will take their place. A 2018 New York Times column declared that sex robots’ contribution to sexual redistribution (ensuring everyone has access to fulfilling their sexual needs) is inevitable. One of the main reasons for this is the assumption that there is no complexity of consent involved with sex robots.

Only, it isn’t that simple. It is necessary to start viewing sex robots for the potential they hold — both independently and as a reflection of how society will continue to treat women. As Frank and Nyholm write, “If we legally incorporate sex robots into the legal community, but we don’t require that consent—or something similar to consent—be required in the context of human–robot sex… It means that the legal community does not take a strong stance against non-consensual sex with human-like members of the legal community. We think that this is an unacceptable implication.”

Aditi Murti is a culture writer at The Swaddle. Previously, she worked as a freelance journalist focused on gender and cities. Find her on social media @aditimurti.

Related

Indian Government to Set Up Public Wifi Access Across the Country. Would You Use It?