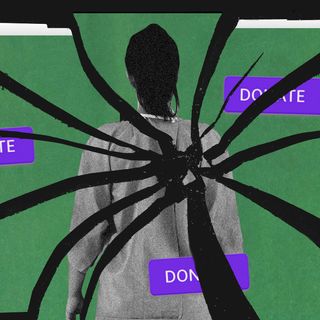

What Happens When Therapists Bring Their Own Gender Bias Into Client Care

“It’s almost like institutionalized violence in a way, where you are reinforcing the notions of the society in the therapeutic context,” an expert notes.

For Vidhatri, it was getting hard to breathe. This is 2019, when she was first diagnosed with depression. Like many other Indian women, she faced pressure to get married. Her parents routinely used various tactics (some subtle, others crude) to find her a boy. This, coupled with the fact her relationship was on the fritz, eventually made her seek psychiatric help.

“The psychiatrist kept telling me how I’m supposed to understand my parents because I’m a ‘girl child’ and how the prestige of my family depends upon me,” the 25-year-old says. Her psychiatrist went on to tell her that a family member had died by suicide because their daughter wasn’t willing to get married to the chosen boy. Not only was this unethical, but it also worsened Vidhatri’s inner turmoil.

“All this when I was vulnerable and feeling suicidal.”

Such gender bias in therapy consciously and unconsciously reinforces societal norms of marriage and family building — pushing those who need support into a corner.

***

“The moralizing judgment plays out in different ways,” Advaita Nigudkar, co-founder of SAAHAS, a queer-affirmative group therapy, tells me. The litany of womanhood is haunting — get married, have children, be okay with men cheating sometimes, focus on home over career, and so on. Phrases like “it’s your fault,” “you should try harder,” work to reinforce the idea that women are responsible for how people treat them and that this can be “fixed” simply by way of their behavior.

Vidhatri eventually sought help from another male psychologist, who kept pushing her into family therapy so that she could “better understand” her parents’ point of view. This despite constantly telling him she doesn’t feel safe with her parents. Dr. Kamna Sarin, a licensed clinical psychologist, notes the many instances where clients felt a similar pressure within the family setup. “There’s a cultural bias that women must be married by a certain age, or a said structure that marriage must look like after say the late 20s.”

This insistence to get married also translates into the pressure to stay in marriages, no matter how emotionally or physically abusive. Someone with borderline personality disorder recounts the “huge lectures” they received constantly — on how they should be less difficult and more passive. “I had been in an abusive relationship for a long time and my previous psychologists slut-shamed me for having sex with that person out of marriage and kept calling me a ‘psychotic’ all the time,” they said.

Related on The Swaddle:

Is Your Therapist Responsible for Making You a ‘Better’ Person?

On the other end of the spectrum lies another woman’s experience: “I had depression arising out of my conflicts with my now estranged husband. He took me to a psychiatrist for counseling and later had his friend, who is a psychologist, collude with the psychiatrist I was seeing, behind my back.” She was told she has bipolar disorder and depression.

“Marriage is just one thing; people have such strong views about abortion where it could come in as well,” explains Richa Vashista, the Chief Mental Health Expert at a mental health platform working with women and LGBTQIA+ individuals. “That can absolutely not be a safe space for a woman.” Instead, it becomes an advertisement of the acceptable way of life: monogamous and domesticated.

Shame is a running epithet; women are slut-shamed, body-shamed, victim-blamed, and pushed into unreservedly accepting traditional Indian values. “I could not ignore [the therapist’s] casual remarks about how shabby I looked, or why I wore my hair short, or how I have been gaining weight. That is when the therapist went on to suggest that ‘looking better’ could help me get out of depression,” a woman noted, adding that she was told to comb more.

Women who face difficulties at the workplace — not only because of harassment — but due to microaggressions and sexism, are encouraged to undergo therapy because of their emotions and “issues.” “Women are very angry about it; they have been told that you shouldn’t be angry, and that anger management is the problem,” Jagruti says. A 2019 study also found women who face sexism are three times more likely than men to experience poor mental health.

There is also a hesitance around sexuality and desire in the conventional therapy space. Advaita recalls how a client felt “judged” by a previous therapist when they spoke of having multiple sexual partners.

Rachelle, 30, came out as non-binary (NB) some years ago. “I’ve been in therapy for about 10-12 years now. I have had anorexia since I was 16.” But Rachelle’s experience with finding the right gender-affirmative therapist took years, especially as a Dalit person. Caste location, sexuality, gender identity, class are all deciding factors in how different people experience therapy.

That psychosocial factors — like domestic violence, caste violence, and workplace harassment — affect women disproportionately has already been widely established. This makes women more vulnerable to anxiety, depression, PTSD, among other conditions. According to a 2020 Lancet Psychiatry study, more Indian women suffer from depression and anxiety disorders than men. Added to this are barriers in terms of transport, economic, privacy, and space to access therapy.

Related on The Swaddle:

How the Indian System Keeps ‘Single’ Women Dependent on Others

Arguably, these challenges apply to people across genders. But the bias plays out a little differently. Mental health activist Bhargavi Davar’s research shows the origins of psychoanalysis in India; upper-caste elite males introduced the world of mental health care. This consequently meant that the lived realities of women, let alone those of people with intersecting marginal identities, were excluded from the narrative. “This has led to psychoanalysis and most other psychological schools of thought to ignore structures like patriarchy, caste, religion, and even regional differences,” Davar argued.

When practitioners frame the person as the problem, the intent is to change the individual’s thoughts, attitudes, or behaviors while saying nothing of patriarchal structures that cause the problem. The end result is the person internalizing all of this — “to such a level you don’t even identify [Savarna patriarchy] this is causing you pain thus becoming an enabler of brahminical patriarchy. Then you’re sort of perpetrating and enabling it in some way,” Rachelle explains. “It’s not acknowledged, discussed, or spoken about.”

This can make the process grueling. “It really shakes us, because we go to them for advice and get treated but when they try to reinforce their pseudo values it makes you believe yourself even less,” Vidhatri says. “I dread going to a therapist again.”

If a woman in an abusive relationship is told to stick it out because it happens to everyone else, “she is going to internalize a lot of these beliefs, and it’s going to cause a lot of irreparable damage,” Jagruti says. “… you can come back having some of your unhealthy belief systems reinforced even more stringently.”

“It’s almost like institutionalized violence in a way, where you are reinforcing the notions of the society in the therapeutic context, and you’re causing harm to the client in doing so.”

Is therapy, then, a safe space, a room to heal, or a reflection of culture’s morality?

***

“Therapy has to be devoid of morality and concepts of ‘good’ and ‘bad’; it has to be a completely non-judgmental space,” Advaita notes. Mental health practitioners face greater self-accountability; remaining committed to a lifelong professional idea of training yourself, teaching yourself, and constantly checking in with yourself, Advaita points out. “Because there are no external checks on you.”

Licensing in India presents a confusing picture. The Mental Health Care Act, 2017 recognizes four kinds of professionals: psychiatrist (with an MBBS degree and a diploma), clinical psychologist (who is only classified by the RCI), psychiatric social worker, and psychiatric social nurse. Rajya Sabha passed a National Commission for Allied and Health Care Professional Bill this year, which seeks to bring others such as psychologists, therapists, social workers, counselors, and therapists under one umbrella through a registration process. It’s a whole “mess,” Advaita says, referring to the pushback from the practicing community for the lack of licensing exams.

The lacking ethical guidelines play out in multiple ways. For gender non-conforming individuals, for instance, heteronormative conventions in therapy translate into the pseudoscientific practice of “conversion therapy.” While Tamil Nadu became the first state to ban the practice in India this year, there is no existing legislation to prohibit this. The new Mental Health Care Act provides a feeble safeguard by requiring the patient’s consent, the abhorrent practice continues via more subtle channels.

Then there is the matter of patchy curriculums. The 2016 Training Manual for Psychologists, as released under the National Mental Health Programme, for instance, doesn’t make any reference to the gender-sensitive approach — much less recognize intersectionalities. “It’s patriarchy plus the general belief that psychology [as a field of science] is supposed to be very cut off from social issues, which is not true at all,” Jagruti notes. “It is also who’s making these guidelines and who’s making these modules.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Pandemic Isolation Intensified Gender Roles — and Women’s Anxiety, Depression: Study

For Rachelle, as a non-binary, Dalit individual, the intersectionality of identity remains at the core of their mental health discourse — which most curriculums barely gloss over.

Richa, who did her master’s in clinical psychology in 2014, remembers there was nothing in particular taught about women-related mental health support. “I took the effort to understand a lot more in terms of women — postpartum depression, women’s mental health, domestic violence, additional training and readings, all of that together,” she says. That was greater than the actual education provided.

***

The gaps in mental healthcare for intersectional identities are slowly being plugged by trauma-informed therapy or feminist therapeutic practices. The perspective — that patriarchy, gender-based violence (emotional and physical) are real things — is necessary for the practitioner to have. “Using a feminist approach is very important,” says Richa Vashista. “It looks at women and at the multiple identities they can come with… keeping in mind that a woman coming in a therapy room may have a history of any oppression.”

It becomes important to look at women not only from a personal lens but a political one. Jagruti recalls the woman who sought therapy due to workplace misogyny. “As a feminist therapist, I tell them, of course, you’re going to angry, because you’ve been treated badly. Your anger is 100% justified. And the microaggression you experience is unfair.” It is something a lot of women experience disproportionately because of their gender.

To counter victim-blaming, the idea of asserting the reality of gender bias is important. At the same time, respecting their agency to make a choice for themselves without telling them to do one thing or the other remains at the core.

The second aspect of feminist therapy involves helping women unlearn internalized notions. Helping them realize it’s not them; it’s patriarchy. Called psychoeducation, this may involve unlearning active biases and misconceptions about things like consent, violence, gender roles. “A lot of young women will come in and talk about instances of non-consensual sex, and they don’t even realize it was non-consensual,” Jagruti points out.

Feminist therapy in practice, however, remains stigmatized. Experts note middle-aged women may find themselves hesitant; even some practitioners would. Feminism is still such a “triggering word,” Advaita points.

But “feminist therapy was developed as a response to conventional therapy that privileged the knowledge and methods of male psychologists, and foregrounded the experiences of women,” The News Minute noted. This doesn’t mean it prioritizes the experiences of women only; but any group that is emotionally and mentally marginalized. Even men.

Intersectionality in feminist therapy cannot just be a word that’s tagged on. As Rachelle notes, often “there is a focus on feminist intersectional practices, but it isn’t completely intersectional. It doesn’t consider the complexities of identity in gender and caste, mostly because there are very few people from the Dalit community and trans community in the field of therapy.”

“For me, therapy also means practicing community work. That is where a lot of healing happens,” Rachelle adds. Zir is referring to community spaces where OBC, Dalits, Adivasi trans people — places which carry all those deemed “unwanted” by the Brahminical system. For mental health practitioners, it may help to take note and even integrate these practices.

“Healing is not one person’s work,” Rachelle says. “Healing has to happen when we acknowledge that we contribute to certain things — and then be reflective of that.”

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

The Dark Side of Crowdfunding for Health Emergencies