What Is a Constant Lack of Digital Privacy Doing to Our Mental Health?

“As human beings, we want a sense of agency and choice around our own lives. We experience that internal distress as we see it getting taken away.”

Some days, Shahrukh gets the gnawing feeling he’s living in an episode of Black Mirror. The latest hint of this breach in reality came when he was admiring an international brand’s selection of handbags with a friend, talking about how ridiculously expensive they were in India. The next thing he knows, Shahrukh is getting ads on Amazon – with an “UP TO 40% OFF” flashing in red.

This is not a unique experience. Substitute platform, people, the topic of discussion – virtual advertisements today loyally reflect a nugget of everything being discussed in real life. Such interactions between data and our lives have become the norm, not anomalies. However, this feeling of constantly being watched, tracked, and surveilled can be rather disquieting. The lack of privacy induces a crisis of liberty for individuals – a feeling that you’re out of control.

“The level of information that is compromised between apps and service retailers is uncanny and frankly disturbing,” says Shahrukh. “It feels straight out of sci-fi sometimes.”

***

“As human beings, we want a sense of agency and choice around our own lives. We experience internal distress as we see it getting taken away,” explains Jahenzeb Baldiwala, a clinical psychologist.

Smart, sophisticated ways of surveilling people and their identities are becoming so ubiquitous that trying to quantify them is like measuring the air around us. Web browsers store snapshots of our interaction with the internet via cookies; this data is used by retailers, governments, banks for several purposes. There is facial recognition technology embedded in our phones, on the streets, in classrooms. The phone taps our location (via Google Maps, WhatsApp, and a spade of other apps demanding access to our geography). Conversations with voice assistants like Alexa and Siri are vigorously recorded and stored, as one researcher found. Government IDs are linked to one another under the guise of uniformity and simplicity, even though experts have long cautioned about the vulnerability of umbrella digital systems like Aadhaar being prone to misuse.

Rohini Lakshané, a technologist and public policy researcher, further notes how corporate surveillance overlaps with individuals; personal health and financial information become vials of gold for advertisers, banks, insurance companies, credit bureaus, lending entities, corporate hospitals, and so on. Research has also shown the extent to which such data could be weaponized to influence voter perception, ideologies, and even distort realities.

For Shobhan, 27, all this is downright “frightening.” Surveillance feels like nature itself – a state unto itself that we’re meant to live with, not understand or limit. “It’s like you’re being plugged to a mainframe and there’s no way to plug out.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Indian Culture Normalizes Spying. This Affects How We View Digital Privacy

At the very least, a perpetual lack of privacy invades people’s personal space and sense of security, says Namrata Khetan, a counseling psychologist. “This leads to hypervigilance, doubts, constant fears, and paranoia in some cases.” They converge into the larger inability to trust people, surroundings, and things. A study from as early as 2011 found that surveillance is linked to heightened stress, anxiety, and fatigue.

Anushka Jain, 25, is unsettled at the prospect of her phone transmitting her words and identity through the algorithm. “I have a very paranoid idea of interacting with technology,” she says, adding that she constantly feels like under the gaze of a camera. She researches privacy, surveillance, and transparency issues on a social and national level, so the awareness is pointed.

Her laptop’s camera is thus always shrouded behind a physical cover, owing to the fear of hacking or spyware turning on cameras without consent. She deleted Facebook and Instagram in 2020, but the thought of the “kind of data that they collect, who has access to it, and the kind of continuous monitoring that they can do” continues to bothers her.

This need to be perpetually vigilant also leads people to monitor and alter their behavior. “When I’m in the washroom, I’m very aware of either not taking my phone inside or the camera is facing away from me,” she says. “Or when I’m talking to my friends, I’m now hyper-aware of what might happen if my messages or my chats got leaked, if somebody’s got access to what I’m telling my partner or my friends.” Anushka is referencing the media cases concerning actor Rhea Chakraborty and Aryan Khan, where their personal WhatsApp chats were “leaked” to the media after authorities seized mobiles for investigation. When prime-time news relies on invasions of privacy, the anxiety of always being watched is unflinching. One of Shahrukh’s friends joked about how they are “bait for the IT cell”; another came up with the quip: “hope the agent assigned to me at least finds me cute.”

In 2012, Finnish researchers looked at the effects of continuous computerized surveillance on individuals. They introduced video cameras, microphones, and logging software for personal computers, wireless networks, smartphones, TVs, and DVDs. The participants were asked to report their stress levels at gaps of six and twelve months each. In the end, 90% of them noted a sense of annoyance, anxiety, and even anger; one household dropped out at six months because the technology caused significant discomfort.

“There’s the kind of background, everyday anxiety that builds up, we know it’s there, but we kind of ignore it and we don’t realize how on edge we were until it’s gone,” said Brock Chisholm, a clinical psychologist who studied the effects of surveillance on mood and behavior. Constant surveillance, in other words, is cognitively draining, as it pushes the brain into a state of fight or flight.

“Hypervigilance is the norm,” adds Shahrukh. “I feel immensely responsible for my words and actions online. Not only do I fear getting in trouble with authorities, but also from online mobs… who’ll mentally harass you just for your thought.” This is true in some cases; think of how Bengaluru cops last year arbitrarily stopped people on the road to check their phones.

This hypervigilance “makes people more irritable; it will affect sleep [and] your ability to focus over a period of time,” says Baldiwala.

“This also makes us hypersensitive, where we are maybe overthinking everything. Sometimes it can lead to conflicts in interpersonal relationships; issues where you may struggle to let certain things go, or you might pick on things much more – just because you’re so hyper-aroused and sensitive.”

Generally, research has found that the self-concealment of one’s thoughts, behaviors, and feelings takes a lot of emotional labor. It can have negative psychological effects, including anxiety and depression, and can even become a physiological stressor. Further, social and psychological theories state that the home allows for autonomy, isolation, and well-being. Any form of computerized surveillance can disturb all these pillars.

“Indiscriminate intelligence-gathering presents a grave risk to our mental health, productivity, social cohesion, and ultimately our future,” argues Chris Chambers, a professor of cognitive neuroscience.

Related on The Swaddle:

Respectfully Disagree: Is Surveillance Ever Okay?

What’s more disturbing to Shahrukh is how easily people can brush the loss of digital privacy off. “I worry what [all this] may snowball into – because literally, all my information is up for grabs.” For now, the best Shahrukh can do is: “give up on being too ‘radical’ for the internet.”

Anushka too feels like she has to convince others of the need to safeguard privacy. There is a tone of defeatism (“what’s the point, all data is being tracked anyway” or “there’s nothing we can do”) or naivete (“who is looking at our data”) in her friends’ voices when she remotely mentions the steps she takes.

“There is some form of gaslighting that happens when people say you’re not important enough for people to actually invade your privacy,” she says.

If people were less aware of the extent of invasion, would their mental health be better? “Ignorance is bliss,” says Shobhan wryly. “Not knowing is probably living in a bubble, which I guess can be comforting. But it’s only a matter of time.”

Research points out that the impact on mental health depends on how aware we are that we’re being watched, and what we think the motivation is for surveillance. And this is what makes internet surveillance terrifying and unacceptable for some. “You don’t know anything about their motives, or what they might or might not do. In that sense, you don’t know how powerful they are,” adds Baldiwala.

Arguably, to some others, personalized tech might feel like a small price to pay for convenience or security. But this rhetoric points to another conclusion: people don’t understand the concept of privacy very well. Anecdotal evidence shows that Indians trust that their information will not be misused — unaware of the extent to which data is traded. When they were informed, according to a study, people said they were shocked and outraged.

People’s idea of consent and boundaries is diluted too when governments and big tech perniciously invade individual and collective privacy. The Finnish researchers also noted that the participants’ privacy concerns plateaued after about three months, because they got more used to the surveillance. Some hid their activities in the home, some pretended to change their behavior, some transferred it to places outside the home; but, ultimately, everyone became more conformist and subdued.

Arguably, surveillance affects those in minority communities and lower-income groups far more. Activists note the practice of questioning citizens in Hyderabad, for instance, was disproportionately used to target poor citizens, Muslims, and Dalits. Some have even pointed out the gender, ethnic, and casteist bias in how tech surveillance plays out. Take for instance the “Sulli Deals” and “Bulli Bai” cases over the last year, when pictures of Muslim women were taken to “auction” them on different platforms as a form of targeted harassment. At the same time, it’s harder for these groups to access mental health resources.

***

Baldiwala lists some measures her clients take to feel safe: hiding their cookies, turning off phone notifications, deleting apps, de-linking any and every personal data. But the thing about preserving mental health is, it takes awareness and persistence to address a structural issue that is both personal and political. This time, it may demand some amount of defiance too.

A tragedy of the modern age is the desire for freedom while constantly forgoing it for the sake of convenience and efficiency. It takes a lot to be private now; so much effort every day.

But Baldiwala has hope. “People are also always in their own ways responding [to social shifts]. So one hopes that resistance [to this] will also come over a period of time.”

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

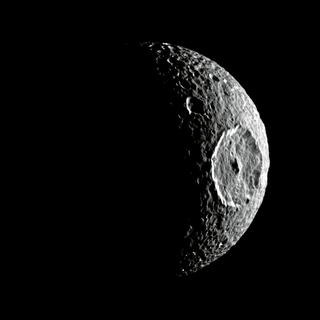

Saturn’s ‘Death Star’ Moon May Contain an Interior ‘Stealth’ Ocean