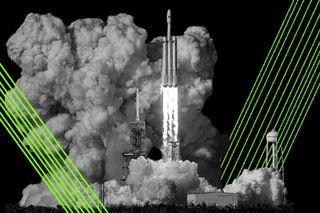

What Is the Environmental Cost of Space Tourism?

One rocket launch produces up to 300 tons of carbon dioxide into the upper atmosphere where it can remain for years, experts say.

The edge of outer space is a fascinating place, which explains why it has transformed into a competitive, private race between billionaires. “Welcome to the dawn of a new space age,” Richard Branson said before his big space adventure last week. Yesterday, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos returned with his crew after a 10-minute flight of fancy.

The dawn, which companies like SpaceX, Virgin Galactic, and Space Adventures, speak of is related to making space tourism more common and accessible to people. But like all “good,” exciting things, it has some caveats. As rockets get propelled beyond the atmosphere, experts have noted the huge environmental payload these flights register across three domains: the land, atmosphere, and outer space itself.

Rockets require a huge amount of propellants to push out of the Earth’s atmosphere. The burning of these propellants provides the necessary energy required for rocket launches.

But in doing so, the fuels emit a host of greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide, air pollutants, water, chlorine, and other chemicals. “For one long-haul plane flight, it’s one to three tons of carbon dioxide [per passenger],” Eloise Marais, an associate professor of physical geography at University College London, told The Guardian. And for one rocket launch, it’s 200-300 tonnes of carbon dioxide.

And naturally, the higher a spacecraft flies, the more fuel it requires. The Space Shuttle orbiter needed almost 720,000 kilograms of liquid fuel to reach space, for instance.

These gases and particles are naturally harmful. Burning fuels like kerosene and methane also produces soot. Soot is known to cause haze, acidification of lakes and rivers, and increase the risk of respiratory infections, heart disease, and lung cancer in people.

Plus, the amount of heat generated adds ozone to the troposphere, the lowest layer of Earth’s atmosphere, where it acts as a greenhouse gas and traps heat.

Emissions from rockets are emitted directly into the upper atmosphere. Notably, roughly two-thirds of the exhaust (containing black carbon) is released into the stratosphere (12-50 km) and mesosphere (50-85 km), where these gases can for at least two to three years, Marais noted in The Conversation. Once there, these particles can reflect sunlight, cause a nuclear winter effect, and even accelerate ozone depletion.

Related on The Swaddle:

Humans May Have Already Committed the First Crime in Space

“The very high temperatures during launch and re-entry (when the protective heat shields of the returning crafts burn up) also convert stable nitrogen in the air into reactive nitrogen oxides,” she adds. This process happens in the stratosphere, where nitrogen oxides along with chemicals convert ozone into oxygen, depleting the ozone layer (which protects Earth from ultraviolet radiation).

The launch also releases water vapor into the upper atmosphere (such as with the burning of the BE-3 propellant), and even something as seemingly innocuous as that has an environmental impact. Water can form clouds – the location of which influences global heating. Clouds, depending on properties such as their density and height in the atmosphere, can either enhance or dampen warming. Moreover, the clouds formed due to water vapor accelerate the process of ozone depletion. In 2020, researchers noted the ozone hole is “large and deep,” at around 24 million square kilometers, it had reached its maximum size.

“The nitrogen-based oxidant used by VSS Unity also generates nitrogen oxides, compounds that contribute to air pollution closer to Earth … Exhaust emissions of CO₂ and soot trap heat in the atmosphere, contributing to global warming,” Marias points out.

“While there are a number of environmental impacts resulting from the launch of space vehicles, the depletion of stratospheric ozone is the most studied and most immediately concerning,” Jessica Dallas, a senior policy adviser at the New Zealand Space Agency, wrote in an analysis of research on space launch emissions published last year.

There are also some concerns about what these launches do to outer space. “Today, launch vehicle emissions present a distinctive echo of the space debris problem,” they wrote. Previously, scientists have pointed out the increase in dead satellites and manmade space junk, leading to an alarming rise in space debris.

“There are around 34,000 pieces of space junk bigger than 10 centimeters in size and millions of smaller pieces that could nonetheless prove disastrous if they hit something else,” experts note.

Related on The Swaddle:

Scientists Discover Cosmic ‘Superhighways’ That Could Accelerate Long‑Distance Space Travel

The scale of emissions due to space tourism is unfathomable. Carbon dioxide emissions for four or more passengers on these space flights are between 50 and 100 times more than one to three tonnes per passenger on a long-haul commercial flight. Even the nitrogen oxides generated during rocket launches is at least four times higher than what is emitted by the world’s largest thermal power plant, Drax. Arguably, the impact of a rocket reaching orbit is significantly higher than these minute-long flights, and their overall carbon footprint still appears to be modest in comparison; but the myopic understanding does injustice to the idea of space travel.

French astrophysicist Roland Lehoucq and colleagues note in The Conversation how these emissions are “roughly equivalent to driving a typical car around the Earth, and more than twice the individual annual carbon budget recommended to meet the objectives of the Paris climate accord.”

As the space tourism industry grows, the lack of regulations around the kind of fuels used and their deleterious impact on the environment is highly concerning. And it is an industry: Virgin Atlantic wants to conduct 400 flights a year. There are talks of building more space transportation, emerging startups in suborbital transportation, and increasing developments in low-cost launching sites — the space exploration industry is estimated to be valued at around $2.58bn in 2031, according to a report.

“We just don’t know how large the space tourism industry could become,” says Marais.

Plus, the timing is crucial. The space race may have inspired wonder in another reality. “[Now], we are living in the era of climate change and starting an activity that increases emissions as part of a tourism activity is not good timing,” Annette Toivonen, author of the book “Sustainable Space Tourism,” told AFP. Which is also why a section of the public discourse has been miffed with rich billionaires flying to space for a few minutes of joyride in fossil-fuel processing metal crafts. All this even as the planet continues to be ravaged by heatwaves, floods, wildfires, with the future only looking grimmer.

More research and climate modeling are needed to understand the tangible impact of another tourism industry. But as Marais says: “The time to act is now – while the billionaires are still buying their tickets.”

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

New Study Shows Resilience Is Not a Fixed Personality Trait, but Changes Over Time