What It’s Like To Live With: Bipolar Disorder

“I know it’s just something I have to live with, but medication and therapy have made it easier.”

What It’s Like to Live With explores the stories of people who see and experience every day a little differently.

The article below mentions suicidal thoughts. In reading further, please keep in mind the content may cause emotional distress.

When I wake up in the morning, regardless of what my mood is, there’s a certain amount of energy I mentally allocate to different tasks for the day. At this point, if I am high on energy, life is great and I can do whatever the hell I feel like. If I wake up low on energy though, I’m caught in an all-consuming feeling of lethargy, where my brain is in a foggy state, and it randomly stops and restarts — making me constantly lose my train of thought.

I have been feeling these ups and downs for years — probably since my second year of law school. It was oddly gradual. I would have these long depressive spells; then all of a sudden, I’d be super happy, super energetic. I didn’t realize it at the time, but it was affecting more than my social life — it impacted the way I would process information, even the way I approached my academics.

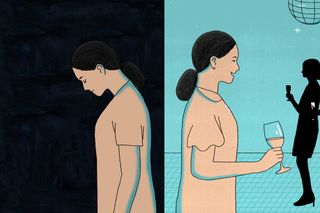

I can’t process information as quickly as I otherwise would during my depressive spells, my reactions slow down, and my sense of motivation is dead, pretty much the usual symptoms of depression. When these hit, it becomes important for me to figure out exactly which tasks need to be prioritized, so that I can allocate energy accordingly. In college, during my high-energy phases, I had absolutely no problem managing a bunch of social occasions since I was energized. In fact, I made spur-of-the-moment plans, and I was known to be quite extroverted, but when the depressive spells hit, I would disappear for days.

My disorder also affected the way I wrote my exams. Even though I knew my course materials well, either I wasn’t able to put my thoughts together coherently enough to be able to string out proper answers, or I didn’t know what to write because my brain felt so sluggish, it simply couldn’t recall anything. And, of course, this affected my grades.

I also get really irritable during my manic phases. All of the energy that I suddenly have seems to come from a very negative space; but physically, I’m more productive because I’m more activated and energized. It’s an odd mix really — if I am in a bad mood when a manic phase comes on, really dark thoughts start creeping in. Sometimes, I end up picking fights with people — especially long-drawn, emotionally-invested political fights with my family.

I’ve had a couple of moments in college when I was ready to pull the plug and commit suicide. To prepare myself for it, I took care of everything I needed to deal with, and I wrote down instructions I had to pass on for other responsibilities in a note. Then I sat with a bucket of water and a brand new razor in my room. But while I was sitting there, contemplating the step I had made up my mind to take, I heard a member of the hostel’s cleaning staff outside my locked door — probably just a foot away from me. It sort of jolted me out of the space I was in. And in that moment, I realized that I was about to compel my parents to come collect my corpse from college. I told myself it was not okay, and that I had to find a way to never feel like this ever again.

Related on The Swaddle:

Unpacking Bipolar Disorder and Its Various Classifications

However, I started taking my symptoms seriously only after I began working. I was staying with my family at the time. To some extent, that was helpful — but they weren’t very understanding of the fact that I function differently, and that my day-to-day life feels very different from theirs. That made it very, very hard for me to maintain a balance between my fairly demanding professional obligations at a law firm, and the social expectations my family had of me. I tried explaining it to my parents but didn’t manage to make any major headway there.

At work, I would take up multiple projects in one go and sort of spread myself too thin when I was high on energy. But eventually, when my energy would inadvertently crash, I couldn’t keep up. This became a cycle and had an impact on my work output. I was lucky that my seniors were accommodating enough to let me take breaks for my mental health — but the cycle was creating a lot of work-related stress.

Things got to a point where I was just frustrated with life — my depressive phases kept dipping lower and lower. And since college, both my manic and depressive spells had anyway been ramping up in intensity. So, when the next high-energy phase hit, I put in my L.L.M. applications to go abroad and get away from it all. After coming to the States, I realized the mental healthcare facility here is so much better than in India.

What had put me off seeking help in college was the psychotherapist we had on campus — she violated doctor-patient confidentiality when she randomly told me during my session what another friend of mine had been seeing her for. How was I supposed to discuss any of my deeply traumatic experiences with her, knowing it could get out? And this was what my first experience with a mental health professional in India was like. But the moment I moved to the States and got my student insurance, I approached a psychiatrist here.

Because I had been planning for this, I maintained a mood journal for two years — to check whether my experiences reflected the regular ups and downs of life, or whether there was more to it. The way my spells used to come on didn’t feel ‘normal’ to me. I was put on medication. The process, however, is a little slow because they steadily increase the dosage to check what works for you. I also started therapy simultaneously to monitor my medication.

Unfortunately, the L.L.M. program was only a year-long, and the classes were too intensive for me to commit to therapy as much as I would’ve liked to — I couldn’t go to therapy for almost two months at a stretch. From time to time I still experienced episodes, where I would spend a lot of money, or make really rash decisions, and it made me realize that I needed to take mental healthcare more seriously. But, my insurance ran out as soon as the program concluded. And that was in the middle of the pandemic — when my mental health was already worse than usual, and I was also hunting for jobs.

I did find another psychiatrist post-L.L.M. though — but it took a couple of tries to find one that worked. I was actively seeking out somebody from my racial and cultural background, so that they can understand the subtleties and peculiarities of the Asian culture, which a lot of white doctors don’t get. I’ve been steadily working with him for about a year now — my dosage has also been increased because the quarantine really took a toll on me. But I’m finally feeling consistently happy — my lows aren’t as low, I can pull myself out of them.

I know it’s just something I have to live with, but medication and therapy have made it easier.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity. As told to Devrupa Rakshit.

Devrupa Rakshit is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She is a lawyer by education, a poet by accident, a painter by shaukh, and autistic by birth. You can find her on Instagram @devruparakshit.

Related

Social Support Can Increase Patients’ Ability to Recuperate, Live Longer: Study