What This Year’s Protest Language Revealed About Societal Outrage In India

Protest discourse reflects a longer-burning evolution in political rhetoric that has led to the match point of 2020.

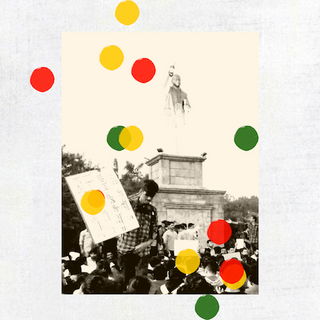

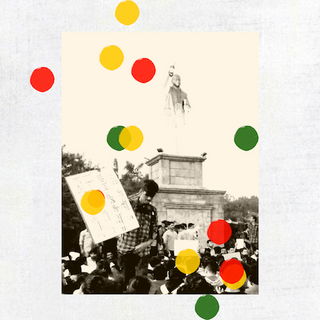

2020 started with chants of azadi (freedom). It is ending with chants of “India Closed.” The intervening 300-some days were punctuated by many other slogans of resistance, many other words of dissent, by lyrics of defiance, poetry of protest, and tales of bravery and violence in a year that will be remembered as much for its social outrage as for its pandemic.

2020 changed not only what we talk about, but also the way we talk about it, furthering a language of dissent that has been building for years. “The level of protests worldwide has remained high for more than a decade, with some of the largest protests in world history,” wrote Isabel Ortiz, Sara Burke, and Hernan Cortes Saenz, academics and policy analysts who study global protests, in June. Their research of the period 2006-2013 analyzed news sources from around the world and concluded economic justice and lack of political representation were the main linguistic themes of protests in that period.

This year marked a shift, however, at least in India.

“Older movements were [talked about as] socio-economic movements,” says Madhura Damle, PhD, an assistant professor of political science at Presidency University who studies the politics of language. Now, “none of these movements are community movements as such, but are being referred to as identity movements.”

Damle points to the current farmers’ protest, which has been painted as a Sikh protest aimed at establishing a Khalistan, though protestors include farmers of many different communities, and the anti-CAA/NRC movements at the beginning of the year, which were frequently described as Muslim protests, despite the presence of diverse faiths and identities within the movement.

“Looking at a [socio-]economic question and reframing it as a community question is deeply problematic,” she adds.

“None of these movements are community movements as such, but are being referred to as identity movements.”

The new framing speaks, perhaps, to a longer-burning evolution in political rhetoric that has led us to the match point of 2020. Protests don’t happen in a vacuum. They are responses to actions or failures by the state, by political leaders – and the language of dissent is shaped by the preceding language of the state. “These are not new conversations – they’re very, very old conversations starting from pre-partition times,” says Papia Sen Gupta, PhD, an assistant professor with the Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, whose research specialties include language and culture. A strong right-wing, Hindutva voice dates back to the beginning of India, emerging now to shape public discourse on a wide scale. “In past few years, there’s been a rechurning of this emotional flare about the State coming up with the narrative of othering, of violence,” she adds.

“We’ve never had these kinds of conversations in schools, with colleagues” like we’re having now, Sen Gupta says. “The word ‘mob lynching’ was not so much in the lingo 10 years back.”

Leaving aside the terror of the act, the phrase is an important marker of cultural shift. “A mob is unidentified,” Sen Gupta says. This mass facelessness reflects the fact that “no political party can just impose a majoritarian narrative – it also reflects [the biases of people].”

The language of dissent in 2020 has forced society to confront that on an individual level – but not in a way that leaves hope for harmonious resolution.

“Conversation [this year] has undergone a major shift,” Sen Gupta says. “Political affiliation has become so overarching that it has affected personal relationships. There’s no mid-point of people coming together and talking to each other.”

While the language of dissent may have underscored the existing lines between us this year, it paradoxically also helped us view protest in a more inclusive way. This year, language particularly helped us reimagine who a protestor is, Damle says. The two dominating protests this year – the anti-CAA/NRC movement at the beginning of the year, and the current farmer protests – have seen women at the forefront. Damle points to Bilkis, an 82-year-old activist who became famous as a face of the anti-CAA/NRC movement in Shaheen Bagh and one of TIME magazine’s “100 Most Influential People of 2020.” Bilkis “became famous as dadi [grandmother],” Damle says. “When we use words related to older men or women, many times it’s derogatory,” but the word dadi conveys respect – for the woman and for what she has to say.

This implication of spoken language can’t be separated from that of visual language, Damle says – both reflect and inform the other. She recalls seeing a news image of a 60-something woman who drove her tractor from her village to the Delhi border to participate in the ongoing farmers’ protests. This image, she says, and others depicting well-dressed farmers eating pizza at the protests, have pushed India to come to a new understanding and appreciation of who a farmer is – a shift that will reflect in our language eventually.

“When we say farmers, we have in mind a poor person wearing a dhoti. Now, we have farmers who are well dressed, having pizza,” she says. “People who criticize the farmers’ protests constantly say, ‘Look at these farmers, are farmers like this?’ Farmers aren’t necessarily poor or uneducated.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Here’s How Protest Slogans Help Grab the Attention of People, Those in Power

But while the language of dissent this year has provided a new lens on old problems, on old perceptions, both scholars are sceptical whether it will yield actual change. “A change in language will matter and does matter, but it’s not that simple. A language change won’t lead to social change, but obviously it’s important,” Damle says. The link between language and social change has been decoupled further by the pandemic, the ensuing lockdown, and the resulting economic crisis.

“If you ask me what individuals on the road are talking about, they are not interested in talking about protests or anything like that. They don’t have enough to eat. The jobs they had are gone,” Sen Gupta says. “Of course a lot of them have anger against the State, but that anger can’t be generated into a language of dissent because people are really, really worried about their livelihoods.”

Despite the mass discourse of protest throughout the year, the outrage that has informed it, and the action that accompanied it, political change has not been forthcoming. “Bihar election results” and “Delhi election results” were among the year’s top 10 Google search terms, suggesting widespread interest and voting action that could reflect 2020’s discourse of dissent, but the ruling party only experienced an electoral setback in one.

“Poverty and inequalities will lead to more protests in 2021,” predicts Isabel Ortiz. Unless the government focuses on one, crucial word that has been notably absent from responses to this year’s protests. A word that could elevate the language of dissent in 2020 into the language of change in 2021: why. “Why we are having these protests is something the government needs to ask,” Sen Gupta says.

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

India Dissents: How People Resisted Prejudice, Patriarchy at Home in 2020