Why Do True Crime Stories Fascinate Us?

“As humans, we want to understand the darker side of our nature.”

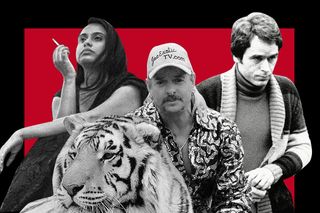

There is something curious about real-life violence masquerading as entertainment. What trumps this curiosity, however, is how these true crime stories rise through the pop culture ranks to become someone’s intriguing idea of “guilty pleasure”; the indubitable success of Tiger King, The Ted Bundy Tapes, and now Cecil Hotel, all attest to the undying popularity of a suspense so grisly, and a specter deeply macabre and REAL.

The human minds’ fascination with blood, violence, and all things grisly is well-documented. It is rather the portrayal of real tragedies that have elevated true crime to a separate genre: covering non-fiction movies, series, books, podcasts, arguably all forms of art dedicated to interrogating the very last grey cells of the ‘criminal mind.’ But why do these bloody stories resonate with us?

Psychologists and criminology experts have some answers: the moribund success is a reflection of human curiosity, thrill-seeking desires, and shows the extent to which we would go to feel safe and protected.

“Humans are naturally curious,” behavioral specialist consultant Tiiu Lutter tells Path Mag. “We have a hard time not gaping at an accident, for example, or police activity. It’s not because we wish bad things for others; it’s just because we can’t help ourselves.” Our visceral response to “stop, stare, gape, and wonder” — that absolute shock value — leaves us transfixed by well-fleshed-out characters and dramatic storylines.

This curiosity also works on a socio-cultural level. Scott Bonn, in his book Why We Love Serial Killers: The Curious Appeal of the World’s Most Savage Murderers, writes, “The serial killer represents a lurid, complex, and compelling presence on the social landscape. … I discovered that serial killers are terrifying and captivating to the public because some of them, such as Ted Bundy, are highly educated, charming, successful, and could easily be a next-door neighbor.” Crime profiles, investigative documentaries, or other cinematographic portrayals give an ‘unseen, unheard’ perspective into the psyche of people who are social anomalies, who eschew all social norms of civility despite looking like us; the quest for understanding what triggered their violent behavior stands out.

A phenomenon called “negativity bias” could also be at play here: our brain pays more attention to negative information than to positive ideas, Krista Jordan, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist based in Austin, TX, tells Health. “So finding out about the ins and outs of what makes someone a serial killer is more interesting than finding out the ins and outs of what makes someone altruistic, because it’s the most negative thing you can think of.”

Moreover, the curiosity also placates moral binaries we were taught as children: killing is bad, and thus, murderers are bad people. While that may be true, the simplicity of this reasoning lacks a sense of profundity that particularly haunts adults, psychologists say — the frenzied actions of a criminal can’t be reasoned out as ‘bad.’ The dualities of good vs. evil, innocent victim vs. criminal mastermind are probed until we realize that people — even those capable of the goriest of crimes — are not unidimensional characters. The quest for these answers, deemed impolite for consideration in civil discourse, is often part of the true-crime genre’s appeal. “If we don’t have problems to solve, we actually get restless and uncomfortable. True crime stories give our brain something to chew on in our downtime,” Jordan adds. Human curiosity is more layered than feeble matters of ‘likes’ and ‘dislikes.’

Related on The Swaddle:

What Makes Us Want to Watch Scary Movies?

She points out another reason why these stories intrigue us: the spectacle of thrill is packed within the recesses of murder and mayhem. “It’s like if you’ve ever heard someone say, ‘Oh my God, that plane crashed. I know somebody who was supposed to be on it but they got rescheduled at the last minute.’ There’s this feeling of having cheated death in some way,” Jordan says — and mostly because we know we can’t cheat death, this adrenaline rush sets itself apart. True crime then becomes an exercise in immersing oneself in dangerous set-ups, without actually jeopardizing our physical safety, and in engaging with real stories and real people in fictive retrospection. “Humans’ bloody fascination with crime and murder has been linked to primitive needs for safety and security, in addition to the desire for certainty and justice,” Mark Lawson echoes this idea in an article titled “Serial Thrillers: Why True Crime Is Popular Culture’s Most Wanted.”

And as long as we’re in a safe environment, the obsession with real tragedies acts as a form of emotional release. The psychological scholarship of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung is an interesting consideration here: both have advocated that humans carry an inherent drive of aggression, dark energies that take shape as ‘melancholia’ and ‘murderousness.’ “The more we repress the morbid, the more it foments neuroses or psychoses. To achieve wholeness, we must acknowledge our most demonic inclinations,” Eric Wilson writes in his book “Everyone Loves a Good Trainwreck,” explaining Jung’s theory. This ‘morbid curiosity,’ as Wilson calls it, is basically to say that watching these stories play out mollifies our sinister urges, as lurid as that might sound.

“So you can listen to a true crime episode about somebody who dismembers and eats their victims and begin to picture in your mind all of the things that are being talked about. You get a bigger bang for your buck than if you were fantasizing about a kickboxing class,” psychologist Krista Jordan notes.

Other experts also offer a less ominous plateau of reasoning: watching or hearing accounts of real tragedies helps people feel prepared and promotes critical thinking. The mind jumps at the prospect of a similar situation: what would do if we were in their place? how can we know if someone is watching/following us? how can we prevent ourselves from being a, or the next, victim? “Watching these television shows can also act as a dress rehearsal for most people. It challenges individuals to develop scenarios to protect themselves and can mentally prepare us for dangerous situations,” Erica Rojas, Ph.D., tells Path Mag. “Think of it like a vaccination for fear,” a previous article in The Swaddle noted, referring to the act of watching scary movies and how it sort of “immunizes” us from fear. True crime stories have a very similar, albeit more chilling, effect.

This school of thought, the one around pre-emptive protection, is also used to argue why women are drawn to crime stories more than men: a growing corpus of research shows that women indulge in these ‘guilty pleasures’ due to pragmatic, self-preserving, feminist, or even voyeuristic considerations. They are active consumers because society conditions them to be so, the argument seems to be. But Rachel Monroe, author of Savage Appetites: Four True Stories of Women, Crime, and Obsession, finds this reasoning to be rather reductive. “Most of the explanations I read for why women are drawn to true crime ended up feeling reductive and unsatisfying. … By presuming that women’s dark thoughts were merely pragmatic, those thoughts were drained of their menace,” she adds. Her alternative hypothesis is similar to what Jung or Freud had in mind: women like grim stories “because something creepy was in us.” And that idea could work for anyone’s fascination for bleak, tragic accounts.

Despite the growing cult, the true crime genre falls on sketchy ground, ethically speaking. Critics have called out the disturbing specter of humanizing someone terrible (in the moral, social, and legal sense of the word), of empathizing with a murderer or a rapist or perpetrator of any violence. Ted Bundy Tapes is a more recent, notable example: Netflix had to ask users not to “thirst” over the serial killer who was convicted for the murder of 30 women. The ethics of obsessing over true crime can be summarized as follows: the pathos of survivors and their families is “outweighed by the genre’s tendency to exploit suffering, lean toward a preconceived narrative, prioritize ratings over morality, and manipulate public opinion,” Rachel Chestnut wrote in the New York Times.

But author Ilana Masad argues that this shouldn’t deter us from “looking at the problem,” which arguably runs deeper. “…look until the layers begin to peel back and reveal the issues at the core of such stories — the systemic inequalities, the co-option of certain stories for political gain, the rhetoric used to make some victims more real than others — that’s the important work that we, and true crime, can do,” she writes in NPR.

So while something like Cyanide Mallika (a fictionalized tale based on real events of India’s first woman serial killer) and Tiger King (Netflix’s eight-episode, enduring wonder) may not have much in common in terms of geography or scope, they still manage to converge at a visceral plain: there is fear, thrill-seeking, empathy, a sense of schadenfreude, guilty pleasure, and embers of social justice. There is no ‘one’ reason why the human mind is piqued — which explains why the canon of true crime has our undivided attention.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Can We Move On: From the Trope of the Feisty Small Town Girl Obsessed With Upward Mobility