Why Gen Z Memeifying World Events Isn’t Trivial

Memes are how Gen Z makes sense of the world. It is politicians and corporations co-opting memes that devalues the gravitas of world events, and supplants the subversive potential of memes.

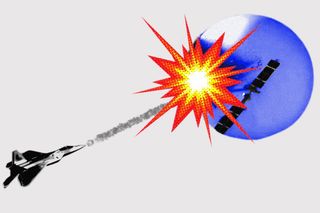

Various facets of the Internet were inundated recently with memes about the Chinese ‘spy’ balloon flying over the US, its subsequent downing, and the perceived ‘overreaction’ by Beijing. Winnie the Pooh (a banned but common caricature of President Xi Xingping) tied to a balloon and armed with a camera, and ‘Who would win?’ tables comparing the American military industrial complex and a ‘Communist’ balloon were a few of the memes created by Internet users, both to poke fun at the powers that be and to highlight the sheer absurdity of the situation. In which other timeline would international, defense-related strikes be communicated in real-time with a global audience? The ability to observe, critique, and satirize the actions of leaders on a worldwide social platform is, on the whole, unique to the youth of today—Gen Z. The successful intersection of memes and politics appears to be exclusive to Gen Z, who deal with the fallout of international crises the only way they know how—through dark humor.

The argument might be made that by using memes, Gen Z are trivializing important topics like politics. There is some truth to this given how we interpret war in real time on social media —images of tanks and refugee convoys appear concurrently with adorable pets, dance crazes, and baking videos. Social media can thus “warp our understanding of what’s happening in the world”—even online, the phrase ‘touch grass’ is a disparaging reminder for users to maintain perspective and logic outside of Internet circles. As Trevor Noah noted on The Daily Show, “one of the strangest experiences of the modern world is following a war on social media. Because all the other stuff on social media doesn’t go away. It just gets mixed together.”

But this ignores the extent to which memes have turned into a language and sense-making device of their own right — particularly for the demographic that grew up on them. Whether it’s a heavily edited screencap of Spongebob Squarepants or a winter gear-clad candid of US Senator Bernie Sanders, the absurdist comedy that Gen Z employs are all “one big inside joke“—a way to cope with the uncertainty, hopelessness, and defeat about the world in which we live.

Related on The Swaddle:

How Serotonin Became the Internet’s Symbol for Hope and Happiness

Moreover, memes themselves have socio-political currency. Although used as a “ubiquitous source of light entertainment,” memes have a greater influence and reach than can be properly measured. A language in and of itself, they are able to transcend cultures and help to “construct collective identities between people”, and are powerful tools for “self-expression, connection, social influence, and political subversion,” according to research. In countries like China, where censorship prevents social mobilization, memes are way to subvert state intervention—the #MeToo of 2018 was replaced by the emojis for ‘rice bunny’ (pronounced as “mi tu”), a translinguistic homophone through which women shared their stories.

Many teenagers only became aware of the Russian invasion of Ukraine through TikTok, writes Kate-Yeonjae Jeong. When twenty-one year old Valeriia Shashenok documented her life in a bomb shelter through a series of TikTok videos in February 2022, she wasn’t doing it to be glib about her situation. Shashenok instead decided to use comedy to share her family’s survival methods and the destruction of her hometown—“I feel like it’s my mission to show people how it looks in real life….In Russia [there is a lot of fake news. And most of the people don’t believe that in my country we have a war,” Shashenok shared with NBC. Her most popular video has amassed more than 6 million likes and shows the TikToker’s daily routine in the shelter—it’s titled “Living my best life 🥰🥰🥰 Thanks Russia!” Dismissing Shashenok’s actions as tactless and writing off her coping mechanism as indifference would be a disservice—whilst aware of the gravity of her situation, Shashenok chose to call out its absurdity instead of the alternative: falling into despair.

This seemingly contradictory mixture of seriousness and levity might seem out of place for any other demographic, but not Gen Z. By memeifying crises, they are receiving “a dose of cathartic psychological relief,” a way to normalize the public processing of difficult events. A study by the American Psychological Association suggested that memes were a way to cope with Covid-19 stress, since “the right meme can make you feel better even when it reminds you of something bad.” Gallows humor has always existed as a sociological phenomenon; it is human nature to offset dire situations with laughter, and memes are merely this generation’s variation. Beyond its mental health benefits, memes allow teenagers and young adults to participate openly in discussion pertaining to political and social developments through a less intimidating channel. The formality needed for high-brow discourse, which is alienating to all but the most educated or accomplished in their fields, is abandoned for accessibility and awareness. It is vital that today’s youth be present and cognizant to global issues—the state of international relations is tenuous enough that even participation in the conversation is valuable, even if that participation comes in the form of an apparently unsophisticated medium.

Related on The Swaddle:

Researchers Try Making Memes Accessible for the Visually Impaired

Yet, amid all the moral outrage, Gen Z aren’t the sole demographic using memes online — but are only disproportionately called out for trivializing world events through them. Many politicians, corporations and business tycoons have begun using the medium to make public statements or engage in diplomacy — arguably, this is when memes are really used to trivialize important issues.

On December 7 2021, the official Ukrainian government tweeted out a meme regarding growing tensions along its Russian border—weeks before the invasion. The Israel Defense Forces, the official state military, shared a Valentine’s Day meme about the “Signs of a Toxic Relationship” calling out Iran from their verified account. “War starts to blend with entertainment,” writes Hayley Phelan. “It was almost as if the tweeters had forgotten they were discussing a complex geopolitical situation, in which millions of lives are at stake—and not just another celebrity feud,” adds Phelan, referring to Elon Musk’s challenging Russian President Vladimir Putin via tweet over possession of Ukraine, and the ensuing responses by users.

“They expect memes to be an “effective campaigning tool,” says Matt Charlton, CEO of ad agency Brothers and Sisters, largely due to the success of Trump’s campaign in 2016. However, paid-for memes are “antithetical to meme-based culture”, says CMU’s Professor Ari Lightman. Bloomberg’s campaign was “corporate advertisement, not the spontaneous, often sarcastic nature associated with viral memes.” This trend of politicians, corporations, and organizations attempting and failing at harnessing the power of memes is only growing. But it’s clear that the linguistic phenomena originally designed by and for young people to make sense of the world has been co-opted by the entities who shape the world — and this is an important difference.

Akankshya Bahinipaty writes about the intersection of gender, queerness, and race, especially in the South Asian context. Her background in political science and communication have shaped her past multimedia and broadcasting experience, and also her interest in current events.

Related

Spy, Cop, and ‘Astra’ Universes Taking Over Cinema, Points to the Marvel‑ification of Bollywood