Why India Is Ablaze With Record Forest Fires

A prolonged dry spell in parts of north India and Nepal, deficient fire services, and manmade activities have contributed to frequent fire breakouts.

Uttarakhand records 45 new wildfires in a period of 24 hours, headlines read on April 5. A massive forest fire broke out at the Bandhavgarh National Park in Madhya Pradesh on March 31. Before that, fires raged for more than 10 days in Odisha’s protected forest reserve, which is one of Asia’s largest. Forest fires are a natural phenomenon and can be isolated instances, but the frequency and intensity of fire breakouts across the country and the Himalayan region show a worrying trend.

Northern states including Uttarakhand, Nagaland, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha, along with neighboring Nepal, have been engulfed in fires for the last six months — fuelling one of the strongest recorded burning events in the past 15 years, scientists say. The peak time for forest fire — the third week of May when the temperature is at its highest — is yet to come.

The impact is evident: fires in Uttarakhand and Nepal have reportedly killed nearly 20 people and even more wildlife; massive chunks of forest land are believed to be razed, and carbon emissions have skyrocketed. The Uttarakhand forest fires emitted nearly 0.2 megatonnes of carbon in the past month, a record since 2003, the European Union’s Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service (CAMS) has found. In Nepal, around 500 fires were burning at one point in March. The consequence on human life, flora and fauna, and the environment is significant — and worsening. What’s causing the severe fire breakout, and why is it different this time?

Experts reason that a prolonged dry spell in parts of north India and Nepal, deficient fire services, and manmade activities are all equally guilty of fanning the flames. Some of the Himalayan nation’s forests and national parks adjoin India’s forested and protected areas, which means that fires can spread both ways.

Forests currently are “tinder dry,” scientists say, due to the absence of snow and rain in the Himalayan region. Three factors are known to contribute to forest fire season: fuel load, oxygen, and temperature. Fuel load means dry, flammable leaves and wood that help the fire burn, and this year, minimum human activity in the region has meant wood and leaves shed during spring have been left in the forest as opposed to being collected for human use, increasing the fuel load. Oxygen flow increased as stronger winds at this time have spread the fire faster than usual in jungles; soils are dried out due to less rain in the monsoon and winter seasons. Lastly, higher-than-normal temperatures in March and April this year are another addition to this perfect storm. “We have not had rain for about five months, so the leaves on the ground have been burning like paper,” Vanoo Mitra Acharya, a wildlife activist, told The Guardian. A study pointed out that heatwaves are becoming the norm in India, and by 2040, they will be unbearable. None of this is good news for the people or the forests of northern India.

Related on The Swaddle:

Huge Wildfires Have Broken Out in Protected Forests, Tiger Habitats of Similipal

The primary reason behind forest fires, however, is the interference of human activities. These include deliberate fires set by locals, carelessness, and farming-related activities. Locals are likely to set fires to promote the growth of good-quality grass and crops; or they may want to cover up illegal tree-cutting or poaching. Some fires are also acts of revenge against community members, including government employees, an Indian Express report noted. The Indian law penalizes any deliberate attempts to set fire in forests.

Echoing this sentiment, India’s National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) doesn’t recognize forest fires as a natural disaster — depriving them of joining the company of tornadoes, floods, cyclones. “… most of such fires are deliberately caused by people mainly for agricultural purposes and, therefore, it is an anthropogenic [manmade] hazard,” Krishna Vatsa, a member of the NDMA, told the BBC. Nearly 36% of the country’s forests are predisposed to fires and almost one-third regions of Indian forest fall under ‘highly vulnerable’ category according to the Forest Survey of India 2019. But while manmade reasons may be one of the reasons for forest fires, local communities end up bearing the impact.

“We wake up in the middle of the night and check around the forests to make sure the fires are not approaching us,” Kedar Avani in Pithoragarh district, the easternmost Himalayan district in the state, tells the BBC. The fires raze agricultural and grazing land, which is a means of livelihood, and erase a sense of protection and community. The Similipal wildfire in Odisha displaced several tribal groups and destroyed the neighboring biodiversity. “Thousands of medicinal plants and saplings which are essential to the forest ecosystem have all been wiped out,” Biswajit Mohanty, secretary of the Wildlife Society of Odisha, told The Guardian.

What makes a bad thing worse is a waning fire service system. The NDMA had previously highlighted deficiencies in the number of fire-fighting vehicles, safety gear, as well as personnel; it has since said that investment in fire services has increased the number of firefighters presently to more than 75,000. But on-ground activists and groups say firefighters are worn out, resources are inadequate, and the administration is not prepared.

The damage is also felt in neighboring cities. Nainital, a hill station with a view of the Himalayas, has been turned into a “smoke chamber” as air quality reached hazardous levels due to wildfires in the nearby range. Moreover, harm caused by wildfires can also impact faraway cities; Allison Hirschlag writes in BBC how “smoke from burning forests and peat can linger in the atmosphere for weeks, traveling thousands of miles and harming the health of populations living far away.” The increased particulate matter poses a range of long-term problems: increased inflammation, a greater risk of heart disease and stroke, and now, Covid19.

At the heart of this remains a larger problem, one centering global heating and climate change. “In the years ahead, temperatures will continue to rise and precipitation patterns will become even less reliable. In such a context, forest fires will become both more extreme and frequent,” Joe McCarthy writes in Global Citizen. Think of this as an unending cycle: more forest fires lead to increased carbon emissions, carbon emissions increase temperature and lead to erratic climate patterns that cause more forest fires. Whichever way you look, the scenario is equally solemn.

What can douse this viciously fiery cycle? Experts say there is a need for pre-emptive action, more preparation, efficient disaster management, incentivizing conservation, and involving local communities in response measures. The government currently struggles with this because of a “trust deficit” between local groups and official authorities — the state blames indigenous communities for destroying forests, while the community calls foul-play for taking away their land.

But as environmentalist Anil Joshi argues in the Times of India: unless those living in or around these forests are involved, forest fires cannot be controlled.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

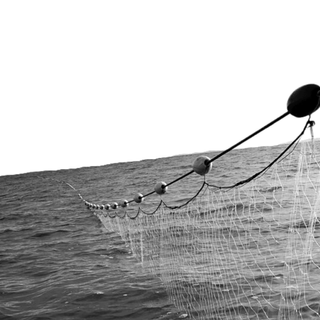

Fishing Vessels Are Using Banned Nets in the Indian Ocean, a Greenpeace Investigation Finds