The ‘Bliss Point’ Is How Food Companies Ensure You Can’t Have Just One French Fry

There is an entire industry devoted to using psychology and neuroscience to keep make junk food as addictive as possible.

If you ever find yourself saying ‘I just couldn’t help myself,’ after eating too much of an unhealthy thing, you are right. It’s not your lack of self-control or will power; there is a highly competitive, secretive and successful food industry that exists only for one reason: to make junk food — from sodas and sauces to chips, cookies, chocolates, cereals, and even artificial sweeteners — as addictive as possible so that we keep on eating.

It’s no surprise, of course, that food companies aim to give consumers what they want to optimize their profits, but the process of product development is actually quite sophisticated, relies on psychology and neuroscience, and is tested rigorously before it’s aggressively and expertly marketed to us. For companies, the entire process is geared towards finding a particular food’s “bliss point”, which is the ratio of three nutrients: salt, sugar, and fat. These compounds trigger all our taste buds together, which further activate pleasure receptors in the brain.

The term “bliss point” was coined in the late 1990s by American market researcher and psychophysicist Howard Moskowitz. He defined it as “that sensory profile where you like food the most”; think Goldilock’s quest for the perfect porridge — a food at its bliss point will make the eater feel that there is not too little or too much, but the “just right” amount of saltiness, sweetness, or richness (from the fat). This perfect point of snackability is what makes the eater reach out for more, more and more. Natural foods also have these three products, but not in the perfect “bliss point” ratio that will make our brains keep eating, independent of hunger levels.

“Junk foods specifically triggers our brain’s “reward zone,” the same area where drugs and alcohol act. Every time you eat sugar, your brain releases dopamine (the happy hormone), and you feel good. In fact, food manufacturers spend millions to find the “bliss point” for each food,” Dr. Darria Long Gillespie, MD, MBA, writes for CNN. “These foods bypass our normal fullness mechanisms, which is why you could eat them all day and not feel full. Over time, your body becomes less sensitive to these foods, so you have to eat more just to get the same dopamine rush and feel withdrawal if you don’t get it. It’s like a designer drug in an easy-to-open package.”

It’s a very precise process, designed to exploit our evolutionary systems’ vulnerability to sugar, fat, and salt, according to Michael Moss, a journalist for The New York Times and author of the book Salt, Sugar, Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us. For our caveman ancestors, foods rich in sugar, salt, and fat were necessary for survival and hard to come by, which is why they didn’t need much in terms of will power to restrain themselves from over-consuming such products. This could explain why the centers in our brain responsible for will power and self-control are evolutionarily young and weak in the face of a multi-billion dollar industry’s efforts to psycho-biologically engineer addictive food.

Technology has clearly outpaced biology now; even though we consume an unhealthy amount of salt, sugar and fat today, our brains remain evolutionarily designed to reward behaviors that procure these nutrients. “Simply put, our bodies are biologically wired to seek out high fat, high salt, high sugar foods – so-called hyper-palatable foods – and the corporations that feed us are profiting from those instincts, all the while putting our health at risk,” reports Mic.

Related on The Swaddle:

We’ve All Been Sold a Lie About Non‑Sugar Sweeteners

This risk has been quantified: we know the harmful effects of excessive and processed sugars, salts and fat; obesity is on the rise globally, and in India; and the situation is projected to only worsen by 2030. All research until now has one factor in common behind these pressing developments: consumption of unhealthy, junk food. But the food industry doesn’t care; in fact, Moss opines they’re not evil corporations trying to make little children sick — all they care about is maximizing their sales and profits. Moss, who interviewed Moskowitz as a part of his research, writes in his book: “Using high math and computations, he engineers them, with one goal in mind: to create the biggest craving. “People say, ‘I crave chocolate,’ ” Moskowitz told me. “But why do we crave chocolate, or chips? And how do you get people to crave these and other foods?”

In his book, Moss also writes about the language people use within the food industry in the quest to answer Moskowitz’s question. Words like “cravability,” “snackability,” “moreishness,” “deliciousness” and “tastiness” that make up the industry’s lingo are not just vague feelings — they’re words that describe the optimum psychological response to a product when the right ratio of salt, fat, and especially sugar are added in. “Mouthfeel” is used to describe how food feels inside our mouths (think a potato chip’s perfect crunch) and introducing a “flavor burst” means altering the size and shape of the salt crystals themselves so that they aggressively land on our taste buds.

One famous example of bliss point research is Dr. Pepper soda, as documented by Moss in his book. When the company was attempting to formulate a new flavor, it went through 61 formulas and 4,000 tasting events across America — presumably costing millions of dollars — demanding that its food scientists continually tweak the recipe until they found the ultimate bliss point. The result: Cherry Vanilla Dr. Pepper, one of the company’s most successful products ever. Another great example given by Moss pertains to Cheetos. The food scientist who was interviewed said Cheetos was “one of the most marvelously constructed foods on the planet, in terms of pure pleasure.” He explained that the most addictive feature of Cheetos is the fact it dissolves in the mouth, which tricks the brain into thinking that no calories have been consumed!

Being able to see the larger game the food industry is playing — one of exploiting our evolutionary weaknesses using science to get us addicted to ultimately harmful nutrients just to maximize their products — is crucial to beating them at their own game. While our collective furor against tobacco companies manufacturing and marketing products has successfully led to its strict regulation, the food industry continues to put out equally, if not more, addictive and damaging products. “They may have salt, sugar, and fat on their side, but we, ultimately, have the power to make choices,” Moss writes in his book almost motivationally. “After all, we decide what to buy. We decide how much to eat.”

Pallavi Prasad is The Swaddle's Features Editor. When she isn't fighting for gender justice and being righteous, you can find her dabbling in street and sports photography, reading philosophy, drowning in green tea, and procrastinating on doing the dishes.

Related

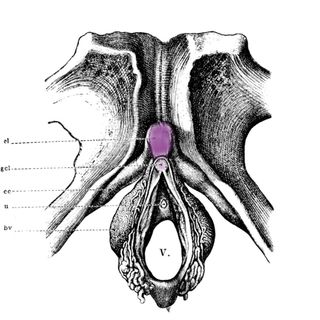

New Study Suggests the Clitoris Has a Reproductive Function