Why Scientists — and Science — Need to Be at the Center of Celebrating Chandrayaan‑3’s Success

Chandrayaan-3 carried the Indian flag to the moon, but the scientists and the science that made it happen aren’t celebrated enough.

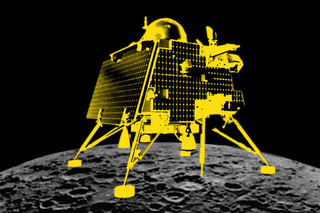

Chandrayaan-3 allowed India to make history on Wednesday, with the lunar mission’s Vikram Lander finally arriving on the south pole of the Moon — the first country ever to do so. India has also become the fourth country to land anywhere on the moon. Chandrayaan-3 is a geopolitical success, intended to advance India’s soft power and technological prowess internationally as a matter of national security. But the real success belongs to the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) scientists who made the accomplishment happen — and it’s also a reminder to support the sciences across all fields, even if they can’t hoist the Indian flag on new surfaces.

Take, for instance, Chandrayaan-3’s objective: studying the lunar surface. To that end, it was sent with a thermal probe to check the surface’s “stability zones for resources like frozen water,” along with a lunar rover containing spectroscopes to study lunar rocks and soil, The Wire reported. The mission is hoped to inspire other scientists “to step forward and play lead roles in the emergent and inevitable global quest for Moon-based scientific and technological enterprise,” cosmologist Tarun Souradeep told Nature. The South Pole of the moon is considered a challenging region and has drawn scientific interest for its potential water reserves and craters that could provide clues to the early solar system’s composition.

That nationalism has overtaken the conversation around the scientific landmark is evident in the way many Indians reacted to the news. Some have taken it as an opportunity to express Islamophobia by invoking Pakistan. Still others began to highlight the women involved in the mission, with news outlets calling them “saree trailblazers” and several forwards and tweets calling them “real” feminists for their traditional attire and contribution to science — a phenomenon that undermines the women’s achievements by only praising them to put other women down. Importantly, much of the media coverage and rhetoric has credited the ruling party — and the Prime Minister — for the mission’s success. Arguably, the lunar mission has turned into a vehicle for many to express prejudice — at the cost of the scientists who made it happen.

Related on The Swaddle:

‘Mission Mangal’ Infantilizes ISRO’s Women By Over‑Simplifying Science

But at its heart, space exploration is about humanity, even if individual rovers carry different national flags. It also furthers the progress of the natural sciences. “[P]eople are looking for things to celebrate and satellites are a proxy for national pride,” noted Jaganath Sankaran at the Center for International and Security Studies at the University of Maryland.

India’s space exploration goes all the way back to independence, when the country sought to prove itself as self-sufficient. While the United States and the Soviet Union were locked in a space race to put humans on the moon, India’s priorities were more practical — strengthening satellite capabilities to survey crops, natural disasters, and erosion, Slate reported. “If we are to play a meaningful role nationally, and in the community of nations,” said ISRO’s founder Vikram Sarabhai, “we must be second to none in the application of advanced technologies to the real problems of man and society.”

“Having a fleet of Earth observation, communication and navigation satellites for a subcontinent like India is a necessity, not a luxury,” Susmita Mohanty, co-founder and board member of Earth2Orbit, told Slate.

But space exploration’s potential in furthering national security interests, as well as boosting the country’s economy, allow the field to supercede other scientific ventures. Despite this, this year’s Union Budget allocated only ₹12,500 crore to the Department of Space, which ISRO falls under — 8% less than the previous year’s budget. Many have noted that despite ISRO’s previous track record of accomplishing missions on cost-effective budgets, this year’s allocation may not be enough for all that the agency has lined up. This is a concern that carries over from the previous year — with experts noting that future plans to send humans on space missions will require far more support.

But this budget still not as bad as it is for other scientific sectors. The Union Ministry of Science and Technology received only 0.36% of the total budget — prompting the Breakthrough Science and Society (BSS), a collective of scientists, to call it “hopelessly inadequate.” The Ministry houses three major departments: Department of Science and Technology (DST), Department of Biotechnology (DBT), and Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR).

Experts echoed these concerns last year too: BSS noted that 90% of the allocation would need to be used to cover salaries, leaving very little for research. Soumitro Banerjee, professor at Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Kolkata, told Down to Earth last year that the budget was “very low compared to what is really needed for the country to make a mark in the world of science and technology.” Investment in basic scientific research has declined over the years, experts flagged. “The whole emphasis on basic sciences has gone down… If someone claims there is an emphasis on industrialisation, those industries are definitely not built on knowledge,” Banerjee added.

Scientific prowess and knowledge, in turn, comes from education; scientists also expressed concern that the inadequate budgetary allocation for education impacts the country’s overall scientific progress.

“…it is clear that the Union government is bent on implementing the NEP-2020 without making the necessary financial provisions. The Breakthrough Science Society condemns the lack of political will to strengthen education and scientific technological research, as reflected in the Union Budget of 2023,” the BSS statement read.

Chandrayaan-3’s success, then, is most meaningfully celebrated by investing greater resources and support structures for science overall. Scientists, in their turn, are arguably best appreciated through a sustained interest in their work toward advancing not only knowledge but its practical implications for society.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

Woe Is Me! “I’m Queer, But Don’t Know How to Identify. Do Labels Matter?”