Why Some Images Become Unforgettable

Why images leave a mark is not just because of someone’s personal story, but because of the symbol they represent within.

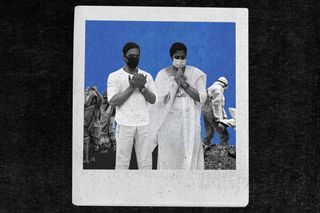

February 6th felt like a day of collectivemourning. But there was one image that captured every Indians’ imagination more profoundly than any others. A belovedactor stood comfortable in his religious identity, offering prayers as a Muslim man for a Hindu woman’s journey into the afterlife. This, despite being harried by virtue of his religion, his nationalism was thrown into question on more than one occasion. The two symbols of prayer — one woman with folded hands and one man with upturned palms — became an unequivocal representation of a phrase Indians know so well in theory — but seem to never have grasped in meaning.

Now, the image offers an authoritative proof of kindness — the aphorism of “unity in diversity.”

Throughout history, similar portraits have gained almost a mass appeal. “These are the dramatic images that are embedded in our culture. They have come to define a historical event, a famous person — or maybe even an entire generation,” as Kyle Almond described in CNN. These photos are reproduced in different periods and flow through time via different mediums. Think the “VJ Day in Times Square” (when an American sailor kissed a woman at Times Square without consent), Buzz Aldrin walking on the moon, India’s 1983 World Cup victory. Or in more recent memory: a father carrying his son while marching along the paths of a migrant crisis, or funeral pyres with an avalanche of the Covid19 dead feeding hungryfires.

The theory of what makes a picture “iconic” or “unforgettable” feels rather instinctive at the outset. It speaks to a singular or a mix of human emotion, an inarticulate feeling that lies deep within us. “I think the most important common denominator is that they strike us on a very deep emotional level, and the emotions are usually some of the deepest emotions that a human being can feel: heroism, fear, grief, joy,” said Peter Howe, who was once the picture editor at New York Times Magazine.

If Covid19 pyres were grief about a national tragedy, 1983 was about unflinching joy about a national victory. Memory also harkens back to the gun-wielding man who shouted “Jai Shri Ram, Yeh Lo Azadi” slogan at an anti-NRC rally in 2020. Or the infamous saga of JNU-violence assailant Komal Sharma, who was identified from a CCTV recording but has become notorious for her ability to vanish into thin air. To a perceptive Indian, these two images inspire a sense of unease and fear — of state-sanctioned impunity and intolerance.

There is also a deep symbolism embedded in every pixel. Looking at this photo of Kushwahas, a family of migrant workers who traveled from Delhi, the meaning spills beyond the two subjects in the frame. “Maybe the personal story got the initial angle or initial reaction. But why this carries over time is not just because of that personal story, but also because it represents something bigger,” explained Sanne van der Leoff, the exhibitions manager at World Press Photo Foundation of the symbolic power of iconic images.

Related on The Swaddle:

Why There’s More Distraction, Less News in the Media

In this case, Kushwahas represented a political and economic crisis, a moral collapse of a pandemic-ravaged society. The striking images from the farmers’ protest related to a similar rot of injustice, exploitation, and collective resistance.

Symbols of resistance, in particular, tend to become powerful aesthetics that are forever enshrined in public memory. In some ways, they have the ability to be resistant in the most powerful of ways. In response to the current image of Shah Rukh Khan in question, it is this very power inherent that has made reactionary forces double down on efforts to tarnish the symbol, with some going so far as to insinuate that the actor’s prayer was him spitting. In the background, this image becomes part of the public debate, and in some ways, shapes it too.

The frame of reference is key here. One pattern experts have observed throughout important images is of portraying one person or highlighting one story; “it personalizes the story,” as van der Leof noted. The bigger story in question is one of fundamental hate and politically-engineered discord. From Muslim girls being denied education to journalists arrested under arbitrary sedition and terrorism laws, the assertion of religious identity from the country’s beloved icon seems invaluable.

Moreover, an unforgettable image carries the distinct ability to be “one of a kind”; in that, the image captures an exact moment and remains unreplicable. “We see it immediately, we grasp its significance, it’s an exact moment. The photographs could not possibly be repeated,” said John Loengard, a former Life magazine picture editor, of the right place and time factor. This is particularly true for visual documentation of history, of events in the past that make their way to us only through official records and anecdotes, bringing the past into focus.

These images are also appropriated over time and find different mediums to occupy public memory. This could be through coins, postcards, stamps, any relevant record. Arguably, what is unforgettable to some may be absolutely forgettable to others. What remains ineffable in collective memory and what doesn’t is, to a great extent, inexplicable. But there is some research on why there is a common acceptance of some stills as iconic. A survey of 12 countries showed some “iconic” images are better known than others and charted some common factors. People’s proximity to the culture, history, and knowledge made a picture relevant and evocative. Iconic images can be contextually placed within a town — at the same time, they can be placed within a country, a continent, a time period, a sense of identity. One of the pictures shown to the participants included that of M.K. Gandhi spinning a wheel at home (taken by Margaret Bourke-White) in 1946.

Together, they form evidence of a “global visual memory”; a compilation of different times, contexts, people coming together to give texture to the word unforgettable.

There’s no one formula or something that can be mimicked with the intention of producing a great image. While the enigmatic value of an iconic image may not be universal, what’s common here is the public is key to deciding what is iconic, and what is not. “They are particularly strong photographs,” noted Robert Hariman, a professor at Northwestern University, but “what is interesting is how they are picked up and circulated.”

Of course, with the internet, it is hard to single something out as particularly unforgettable. The visual overload makes these symbolic moments feel rather ubiquitous. But perhaps the relevance of an image is not meant to come out in the present, but one that gains value and credence by being circulated and reproduced.

In some ways, these images carry a flesh memory of a moment, a period, a society. They define how we view people afloat on the pedestal of power or those gazing from below; or how we see tectonic sociocultural shifts. As van der Leof summarizes: “[Iconic images] are shaped by public opinion and collective memory, and this is different from one country to another. And in the end, this is what makes them so complex and famous.”

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Woe Is Me! “I Don’t Like That My Boyfriend Masturbates to Other Women. Am I Being Unreasonable?”