Why Some People Are Unable to Form ‘Mental Images’

Called “aphantasia,” the condition is common among at least one-third of the population who lack the ability to visualize.

The mystery of why some people “see” things visually and some don’t has endured centuries. It was first referenced by British naturalist Francis Galton, who, in 1880, asked 100 people to draw the image of a table they had breakfast on everyday. The failure to recall the wooden structure, texture, and height inspired a pursuit to understand the mystery of mental imagery.

More recently, an internet challenge asked people to picture an apple, renewing discussion around this human experience. “I see nothing in my mind… [but] I can tell you exactly what an apple is meant to look like. I can list the right dimensions, where light hits, the stalk length, the vibrant color, the unique markings, but there is absolutely no way I could see what I describe in my mind,” one person said. The mind’s eye, people noted, doesn’t always work.

Called “aphantasia,” the experience of being unable to form visual images is explained in a new study. Phantasia means “imagination” in Greek, leading to the term “aphantasia” and its polar opposite “hyperphantasia,” where people have extremely vivid mental imagery. The research, published in Cerebral Cortex Communications, focuses on the neurological factors behind this formation of mental images and also explores the implications on memory and personality.

“For many, visual imagery is intrinsic to how they think, remember past events, and plan for the future – a process they engage in and experience without actively trying to,” Zoë Pounder, a researcher of visual imagery who was not part of this study, wrote in The Conversation. Further, imagining things visually is also known to influence perception and emotion. Other studies have also shown its relationship to creativity.

People who have a robust visual imagination — “hyperphantasics” — have a stronger connection in their brains between the visual network, which processes what we see, and the prefrontal cortex, involved in cognitive abilities, decision making, and attention. Due to this strong connection, the visual networks become active and influence our visual imagination.

For people with aphantasia, the opposite happens. “Our research indicates for the first time that a weaker connection between the parts of the brain responsible for vision and frontal regions involved in decision-making and attention leads to aphantasia,” Professor Adam Zeman one of the authorsfrom the University of Exeter in the U.K., said in a press release. Aphantasia is estimated to be experienced by 2% to 5% of the population.

Related on The Swaddle:

Imagination Can Be Used to Control Fear

The researchers undertook brain imaging among people with aphantasia, hyperphantasia, and people with mid-range imagery vividness — while they were relaxing and “mind wandering.”

The study also coupled brain scans with personality tests. Aphantasics tended to be more introverted and hyperphantasics more open; but there is varying research on this.

In terms of memory, Professor Zeman and the team found that people with hyperphantasia produce richer descriptions of imagined scenarios or even personal details. Aphantasics, on the other hand, had a lower ability to recognise faces.

A separate study published in CORTEX earlier this year explained more about the impact of varying visual memory — and how people recall details of an object if they can’t see it in their minds. Researchers from the U.K. and the U.S. assessed visual memory of participants with aphantasia, hypephantasia, and those with medium imagery. In the study, participants were shown three images — of a living room, a kitchen, and a bedroom — and were asked to draw each from memory. Their drawings were reviewed by an online community of over 2,700 scorers who assessed the objective details (what objects looked like) and spatial details (the size and location of objects).

The researchers found all groups were able to draw the object; the drawings by people with hyperphantasia were richer in detail and color and they were also able to more faithfully remember autobiographic events — things that happened in their life. Although even participants with aphantasia were able to draw objects of the correct size and location, they provided fewer visual details, such as color, and also drew a fewer number of objects compared to the average images.

Related on The Swaddle:

Why Some People Sleep With Their Eyes Open

The observations are in line with other research. In 2003, a person with aphantasia approached Professor Zeman. Zeman told Scientific American that he asked the person which among grass or pine trees had a lighter color of green — thinking he would imagine both the trees for comparison. The patient answered correctly but noted that he wasn’t able to conjure an image to make the decision. So while people with aphantasia might not be able to recall the image in mind, they can still reproduce it or make judgments.

Moreover, association through language was also important in linking two things. “Some participants with aphantasia noted what the object was through language – such as writing the words ‘bed’ or ‘chair’ – rather than drawing the object. This suggests those with aphantasia could be using alternative strategies such as verbal representations rather than visual memory,” Pounder said. For example, the phrase “burning red” or “verdant green” would still mean the same thing, albeit with the absence of visual imagery in people with aphantasia.

She notes that research shows some people with aphantasia may experience visual imagery within dreams; but for others, dreams are made up of conceptual or emotional content.

While these findings focus on the ability to imagine visually, not everyone with aphantasia has a complete lack of imagery experience across all senses.“Some might be able to hear a tune in their mind, but not be able to imagine visual images associated with it,” Pounder says. Think “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” — for some the song could evoke disparate visuals of a guitar and perhaps tears; for others, only the tune would come to mind.

However, aphantasia should by no means be viewed as a disadvantage, researchers say — it’s a different way of engaging with the world. “… what we do know is people with aphantasia live full and professional lives. In fact, it’s been shown that people with aphantasia work within a range of both scientific and creative industries,” Pounder says.

She adds: “As aphantasia has shown, many of our mental experiences are not experienced universally. There are in fact a number of unknowing yet intriguing variations amongst us.”

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

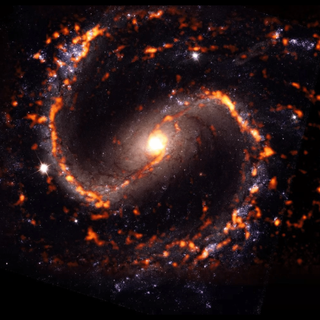

Astronomers Map More Than 100,000 ‘Star Nurseries’ To Show Where Stars Are Born