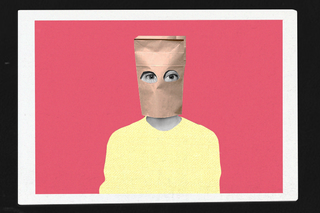

Why We Always Think We Look Bad in Pictures

People have an idea of how they look, and any information that contradicts this image can be disappointing.

It is universally acknowledged that a person with vanity (or dignity), may always eye their own photograph with disappointing curiosity. The outcome of “smile, please” or “say cheese” is never what one wants it to be. It almost feels like a universal conspiracy that every picture is a bad one irrespective of how one poses. Finding the “right light” is akin to solving a quest.

“Bad” pictures, which mean different things to different people, have little to do with how one looks and more with how one wants to look. In other words, there is a glaring ideological disparity between the mind’s eye and the camera lens.

Three theories can help explain one’s hatred of self-portraits. In 1968, a psychologist named Robert Zajonc argued people react more favorably to things they see more often — there’s a familiarity bias at play. He called this the “mere exposure effect.” People see themselves mostly via mirror images, which are flipped versions of themselves that become the preferred self-image. “According to the mere-exposure effect, when your slight facial asymmetries are left unflipped by the camera, you see an unappealing, alien version of yourself,” Wired explained. In other words, the camera version is like an unfamiliar portrait of ourselves that we neither recognize nor care to.

And truth be told: most faces aren’t symmetrical either. Claus-Christian Carbon, a professor of psychology at the University of Bamberg, Germany, even notes people are more likely to note asymmetrical features like nose and ears. “If you have a very symmetric, very easy to process face, then you have one problem: You won’t be remembered so well,” he told Nautilus, taking Meryl Streep’s example whose nose leans slightly to the left. “The little imperfections of her face can be [read] as a sign of authenticity.” Interestingly, a 1970s study also found that other people — friends and family — always preferred the true image (the non-flipped) one of a person.

This opens a paradox. People remember asymmetry more, but also tend to look down on it.

Related on The Swaddle:

Additionally, self-enhancement bias skews self-perception. Some research shows people tend to think they’re more attractive than they are. In 2008, researchers asked people to pick themselves from a line-up of altered pictures — some edited to look less attractive. People chose the photo of themselves in which they looked more attractive — recognizing a more attractive, flipped version of themselves. “It’s a tendency to evaluate our own traits and abilities more favorably than is objectively warranted,” researchers noted, calling this a “self-enhancement” of sorts. If people think highly of themselves, the reality of a picture will always disappoint.

A corollary to this idea comes in the form of “confirmation bias.” People will search for information that backs up our previously held beliefs. If someone thinks they look very attractive in real life, a picture that shows a slightly watered-down version will disappoint them. Alternatively, if someone already has a negative self-image — or thinks they aren’t attractive — they will be more inclined to believe the photograph is bad. In that, people with self-image issues will be inclined to confirm their bias against themselves.

Social media works like an echo chamber to amplify this feeling. “People are comparing their appearance to people in Instagram images, or whatever platform they’re on, and they often judge themselves to be worse off,” Jasmine Fardouly, a postdoctoral researcher at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, told BBC. A 2016 study found a correlation between scrolling and growing disparity with one’s expectations of how one looks.

The composition of the photograph too alters one’s perception of themselves. Because of the “cheerleader effect” (A.K.A. the group attractiveness effect), people think of themselves as more attractive if in a group picture. It is a cognitive bias. In 2003, researchers presented 130 participants with group pictures of three female faces or three male faces. They were also shown pictures of individuals separately. Regardless of gender, people found the group picture more flattering for the said individual. The reason for the illusion may be instinctive: the human brain is programmed to look at the group as a whole. So when it looks to individual characteristics, it is more likely to scrutinize and find issues with it.

Of course, the antidote to bad photo days is seamless filters. But even bad photos — the ones that are poorly lit, blurry, out of focus, unflattering — are a memory worth preserving. The next time someone desires to bend a version of the truth, remember what writer Pamela Paul argued in The Atlantic: “bad photos showed us something we wanted or needed to see.”

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Scientists Find Why Some People Test Negative for Covid19 Despite Exposure