Without Easy Access to Clean Water, How Can Communities Fight Water‑Related Diseases?

Community role models can instill the conviction that good hygiene outweighs inconvenience.

This is the first report in a four-part series that explores the social determinants of living with and in proximity to lymphatic filariasis, a neglected tropical disease.

In Ganjam district, Odisha, a 65-year-old woman briskly hikes her saree up to her thighs and begins her daily routine under the watchful eyes of the area anganwadi and healthcare workers. Living with filaria for 40 years has made M. Satyanarayana Essu comfortable with an audience.

First, she gently lifts a circular, fluid-filled edema, or swelling, on her left leg and slowly begins to soap the lesion within it, then the rest of the leg. She then hoses down her leg with several mugs of water and repeats the careful application with medicated cream. In the background, a pipe drips water into an open gutter surrounding the house.

M. Satyanarayana Essu washes her leg in Ganjam, Odisha. Photos by Srikanta Jena and Shantanu Shou

Lymphatic filariasis, better known as filaria or elephantiasis, is a neglected tropical disease by virtue of the fact that it most often affects individuals who face severe poverty, poor living conditions, and marginalization. Globally, almost 900 million people across 49 countries are at high risk of developing filaria, with 650 million Indians at risk of developing the disease. 90% of filaria cases in India come from only eight states — Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha.

Caused by mosquito bites that carry parasitic filarial worms, the disease is incurable — causing long-term pain, high risk of other infections, and socio-economic consequences for those who live with it. Living with filaria can cause chronic pain, a hindrance to movement via walking and running, and a greater risk of infections due to lesions on the leg. It can only be managed via patient care but is medically preventable via the administration of a two-drug regimen(Diethylcarbamazine Citrate and Albendazole) or a three-drug regimen ( Ivermectin, Diethylcarbamazine Citrate, and Albendazole). These medications are offered for free annually by the Indian government’s Mass Drug Administration program.

Related on The Swaddle:

The Search for Clean Water Puts Women at Risk of Injury Globally: Report

Beyond medicine, a major hope for preventing filaria and other neglected tropical diseases is water — specifically eliminating open, dirty water bodies from living areas and ensuring greater access to clean water for afflicted individuals. Open water bodies like wells, puddles, and gutters are common in village areas — making them a breeding ground for mosquitoes that spread the disease. However, treatment and care for filaria are highly dependent on having frequent access to clean water, which is an uphill battle, as access to the same is severely limited due to poverty and resultant poor living conditions, and a lack of sustained initiatives that aid sanitation habit formation.

The problem is not a lack of general awareness; it is the lack of access to clean living spaces, running water, and frequent information on specific interventions to prevent the spread of disease.

Essu is aware of the impact of sanitation and clean water on her health. She mostly only uses the bathroom at home, and does not store water in buckets for long. “Everything happens at home, if I go out to the village I urinate outside, otherwise, everything is at home. Even the water we use the same day, as we don’t have piped water and have to get it from outside.” This particular awareness of the necessity of hygiene is a common human instinct. K. Suryakanta, an anganwadi worker who also supervises community sanitation meetings and mass drug administrations for preventative medicine, adds, “No one denies [the medicine] as we make sure to wash our hands before giving it.”

The problem is not a lack of general awareness; it is the lack of access to clean living spaces, running water, and frequent information on specific interventions to prevent the spread of disease. This problem finds its roots in poverty, marginalization, and lack of access, which is innate to Indian social structures. For example, tap water, which several well-to-do households have, is a very recent phenomenon — just over 150 years old, according to Aditya Ramesh, Ph.D., who researches water, infrastructures, and ecologies at the University of Manchester. “When the British constructed the first ‘piped water supply systems’ in municipalities across India, piped water reached only a few households in taps, largely European and wealthy upper-caste Indians,” Ramesh says. “It was closely linked to tax-paying, but in fact heavily subsidized by the central government’s agrarian revenue. So in effect, there was no universal water supply that existed, whether constructed by the British, or prior to that.”

Overcoming neglect of the poor and marginalized involves overcoming the enormous problems embedded in India’s economic and social systems. “I don’t think there’s a quick way to ‘solve’ poverty, as it’s a huge, multidimensional problem,” says Nirat Bhatnagar, the head of Dalberg Advisors’ Water and Sanitation practice. “But there have been several attempts to help teach people how to adopt better hygiene habits.” Although Bhatnagar stresses that attempts to train individuals to practice hygiene once or twice are helpful, it’s simply not enough because the end goal is to instill a habit, not just impart education.

Though Essu’s awareness and daily routine of caring for her leg significantly decrease her chances of contracting other infections, the lack of access to piped water at home makes daily hygiene extremely inconvenient. Plus, Essu’s bathroom is Indian-style, and requires buckets of open water for washing purposes. But she is among the lucky in rural Odisha — only 74% of the state’s rural households have access to toilets, even after 33 lakh toilets were built by the Odisha government between 2014 to 2018.

“We’ve all had access to a bathroom with running water three meters away from us, but for a large fraction of India’s population, this is simply not true,” Bhatnagar adds. “They’d have to travel 50 meters away or further to wash their hands, which means it often does not happen.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Water Is Now a Traded Commodity; Can It Still Be a Human Right, Too?

What’s equally dangerous is the open drain near her home that exposes her to several mosquito-borne infections. Both urban and rural spaces that hold settlements rife with poverty see a proliferation of open drains, or naalas, which are often the only affordable source of drainage in less well-off settlements. Open gutters are a breeding ground for disease-carrying parasites and mosquitoes, which are easily spread when they overflow or during monsoon season. Plus, often the only means to control the spread of overflowing drains in rural areas is sweeping the excess water back in the drain, which is a risky, ineffective means to control the spread of disease. For individuals with filaria on their foot, like Essu, contact with dirty water while walking is dangerous, as infectious microorganisms might seep in via the open lesions on their legs.

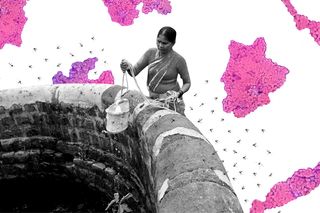

A glimpse into the water supply and drainage systems near where Satyanarayana Essu lives. Photos by Srikanta Jena and Shantanu Shou

Though hygiene habits are unfairly harder to build due to these accessibility problems, they still remain important to develop as a means to ensure the prevention of disease. One means to influence individuals to develop a hygiene habit, according to Bhatnagar, is to have a community role model who influences the behavior of others. In Ganjam district, two sets of people serve that purpose at a community level. The first is the healthcare worker, who interacts with the community on a frequent basis.

Sangeeta Bisoi, a 24-year-old Auxillary Nurse Midwife (ANM) at Suramani Sub-centre in Ganjam district and Mass Drug Administration (MDA) supervisor, says that her major worry when it comes to community health care is that people are unable to understand her guidance properly. “That’s the reason they are facing so many problems. If at all they suffer from any disease, they will take it lightly. That’s also because in Ganjam, they are financially very poor.” However, she still believes that community awareness efforts are important. “We also hold meetings every month. In those meetings, we should make everyone understand. In schools, colleges and anganwadi centres, we should hold meetings and spread awareness about the disease and remove any misconceptions about the disease.” Repeated meetings and awareness-building initiatives can further help build daily cleanliness habits among individuals.

Yet another community role model is the local Member of Parliament. Pramila Bisoyi, the MP from Aksa, Ganjam district, speaks to fellow women, mothers, and children via songs written to help disease prevention. For filaria, she repurposes an old song she wrote in Odiya for malaria (another neglected tropical disease): “Let’s cover up all gutters and drains and unused wells… Burn all the waste straws daily… When our house and the lanes outside are clean… we don’t have to get scared of Filaria ever again. All children, pay attention… pay attention… health is our most precious wealth… Let’s take care of our own health and we wouldn’t need doctors… Diseases will stay away and you won’t fear them anymore… Cook the vegetables and eat it with hot rice… water when filtered is beneficial for the body… scrub your bodies, wash your clothes and stay clean… and you don’t have to get scared of filaria ever again.”

Pramila Bisoyi feeds a preventative drug to citizens during the 2021 Mass Drug Administration round in Odisha. Photos by Srikanta Jena and Shantanu Shou

“India needs to invest in mass media campaigns with a hybrid approach, especially and even during a pandemic. Awareness building that is focused on building demand from communities for public services is the best bet we have,” says Amandeep Singh, a director at Global Health Strategies who works on communications and advocacy around neglected tropical diseases. “Short-term solutions to getting more attention and improved treatment compliance for NTD programs will depend on how we as a nation communicate to the masses and build awareness about the risks of not adopting preventive, promotive services.”

Water and health are intimately interlinked, and the neglect that manifests in providing readily available clean water reflects in the current condition of those who live with filaria. Though there may be sophisticated preventative and treatment plans to rid endemic districts in India of neglected tropical diseases, bridging inequality is the only way to make it go away.

Odiya and Telegu translations by Sangeet Anshuman and Sourav Pattanaik

Aditi Murti is a culture writer at The Swaddle. Previously, she worked as a freelance journalist focused on gender and cities. Find her on social media @aditimurti.

Related

Why People Who Self‑Harm Struggle To Quit