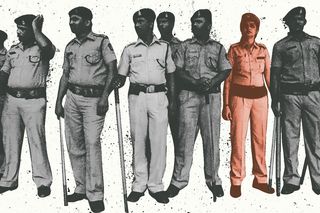

Women Officers Face Systemic Sexism in the Indian Police Force. Here’s How to Change That.

In order to break age-old patriarchal notions and recruit more women in the police, recruiters must abandon the perception that policing is a “male-oriented profession.”

In a telling scene in the recent controversial film, Gunjan Saxena, the character is asked to engage in a fistfight with a male officer to prove her competence. When she loses repeatedly, she is told that it is not the army’s responsibility to provide equal space for her. The film quite accurately identifies the prejudices with which women’s merit is judged within these archaic, colonial institutions.

As a criminal advocate, I work closely with the police institution and interact with officers of varied ranks. Regular visits to police stations have exposed me to the systemic sexism present also within the police institution. The system still does not have adequate space for women to gain equal footing. Reservations about their psychological and physical abilities stand in the way of opportunities, and they are constantly required to prove their proficiency as compared to male counterparts.

They are hardly ever made part of mainstream investigations, with male officers refusing to include them in their teams, citing concerns over vulnerability and lack of physical and mental ability. An ACP once told me, “You know, it just becomes a burden for me to lead a team with women officers in it. You have to think of her protection all the time, cannot keep her engaged till late in the evening, have to send her home early.”

Female policewomen are often branded by their male peers as incompetent. A female officer posted in Bengal explained the existing double standard: “A male officer may be an utter fool but will be called a good officer. You will often see male constables sitting around and doing nothing – and this does not bother anyone. The threshold of credibility is much lower for men, while we women have to keep proving ourselves.”

To further exacerbate issues, there is a lack of basic infrastructure for women, such as accommodation and restroom facilities, in a police station. While discussing these issues, a few lady constables of the Bengal Police explained the particular difficulties of being a woman in police – the erratic, unfixed working hours that often extend up to 24 hours without adequate facilities or even restrooms. When Gunjan Saxena is forced to use the men’s toilet in another scene in the film, she is quite plainly told by a male officer, “Ye jagah tumhaare liye bani hi nahi hai” (“This place was never created for you”).

This institutional refusal to make space for women is reflected in a 2019 report, which states that women constitute only 7% of the total police force in the country. Despite the Home Ministry’s 2009 advisory to all state governments to increase the representation of women in police to 33%, a decent rate of recruitment is far from being a reality. Quite often, there are not even adequate female police officers in police stations where they are statutorily required to handle crimes of gender violence.

Related on The Swaddle:

All-Women Squads Are Inspiring, But Not the Answer to Women’s Safety

Women who do get recruited are mostly given restrictive jobs, limited to making diary entries, addressing crimes against women, or answering calls on 100. Even in all-women police stations, women registering women-related crimes does not mean they are investigating those. The 2019 report also highlights that policewomen are more likely to do in-house jobs while men take on-field jobs.

With a dearth of opportunities comes a dearth of promotions as well. There are barely any women officers in high positions (only 0.85% of the total women in the force hold supervisory ranks). Those who make it are faced with various conflicts, beginning with men expressing deep difficulty in taking orders from a woman.

This discrimination and prejudice against women is pervasive. Like the ACP, most male officers consider women as too weak for such jobs and therefore ‘burdens.’ The strength here only refers to one’s ability to showcase aggression and violence when ‘required.’ Therefore, the only way a woman can fit in or become successful is to strictly adhere to patriarchal norms, emerging as a “mardaani,” as shown in the film with the same title. In order to make the statement that women can be great cops too, the female officer had to be portrayed as someone who is “man” enough to beat up people mercilessly.

Patriarchy consistently leads us to believe that being ‘manly’ is the only benchmark (see report). The first female IPS officer, Kiran Bedi, recounts in interviews how she was not given much importance as a junior officer and her abilities were constantly doubted before she proved herself as being capable of inflicting brutal violence. This mindset persists today, even though no research has shown physical strength to predict either general police effectiveness or the ability to successfully handle dangerous situations.

It has been over 70 years since independence, but we continue to cling to a colonial police system. There has been little to no reform in the force in all this time, despite being one of the most important institutions in a society. In order to break age-old patriarchal notions and recruit more women in the police, recruiters must abandon the perception that policing is a male-oriented profession, mainly involving tasks that require physical strength and aggression. The reality is that everyday law enforcement work seldom requires such aggression. Far from what is shown in films, everyday work instead involves routine technical activities.

In cases of gender-based violence, I have often found the investigation conducted by male officers to be severely lacking owing to a lack of nuanced understanding and sensitivity. A 2011 UN report showed that the presence of women police officers correlates positively with reporting of sexual assault.

The police deals with people’s lives and crises; hence, humanity and empathy must be central to their working. They exist not to inflict fear but to protect. With increasing acceptance of women, there will also be acceptance of more ‘feminine’ traits, such as sensitivity, patience, tenderness, warmth, and compassion.

Further, the environment must be conducive to women, and to allow them to be as they are without feeling compelled to discard any traits in order to prove themselves. Men should be trained to accept women working with them as equals as well as taught how to behave with a woman in the workplace. Alongside talks of recruitment of women, simultaneous conversations about building a suitable space for them are also crucial. Only then will we move towards a modern and reformed force that does not celebrate and uphold absurd patriarchal notions within its own structure, in turn perpetuating it in society.

Senjuti Chakrabarti is a practising advocate committed to issues of human rights, gender justice, and education.

Related

Trump Administration Plans to Extend Policy That Cuts Funding To Global Health Projects Providing Abortions