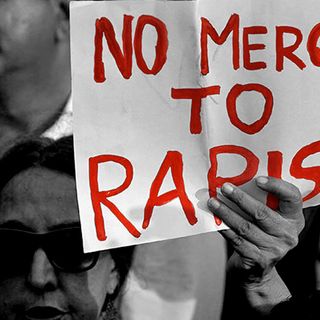

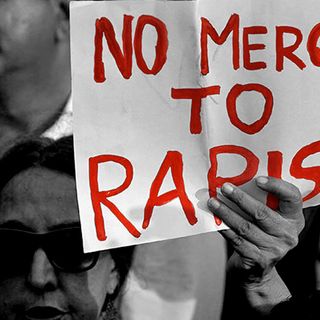

Two former employees are suing the National Commission for Women, alleging they were fired from their positions after lodging an internal complaint of “persistent sexual harassment” against VVB Raju, the organization’s then-deputy secretary, in 2016, reports HuffPost India.

They claim the NCW’s Internal Complaints Committee investigation into their complaints was a “sham and opaque.”

The drama has played out in much the same way sexual harassment cases do in any other organization. The women have accused NCW officials at the time of perpetuating the problem; one of the petitioners claims then-Chairperson Lalitha Kumaramangalam had told her, following her complaint, that the petitioner would need to “improve her performance” in order for her contract to be extended. That petitioner has produced letters from various NCW officials praising her work during her time with the organization. Her contract was extended for six months, but not renewed after that time; the other petitioner said her administrative role was “arbitrarily” terminated shortly after she filed her complaint.

One of the women is still unemployed; the other told HuffPost India she’s afraid for her career if her new, current employer learns of her sexual harassment lawsuit.

Kumaramangalam, whose leadership tenure ended last year, referred questions to the NCW and its employment files for each petitioner, which she says she no longer has access to; Raju has called the accusations “untrue and concocted” and suggested the two petitioners are working together to defame him.

This appears to be a classic case of ‘physician, heal thyself.’ The roots of sexism run deep, and permeate even organizations devoted to the advancement of women. It might seem like an aberration, but it’s not; it’s the norm.

It is possible to exist within and perpetuate damaging gender norms, even as you work to change them. Some would call this hypocrisy; it is. It’s also a mirror of the broader hypocrisy within a society that purports to revere women, even as it punishes women for stepping outside its narrowly prescribed definition of womanhood. Advancing women’s rights, fighting for women’s empowerment is about confronting this hypocrisy and eliminating it. The National Commission for Women has an opportunity to put its money where its mouth is, even this far after the fact. It could be the example in how to effectively and transparently handle a sexual harassment case, with fairness to both accused and accusers. Or at least it could be the example of institutional self-reflection and evolution toward equality in the workplace.

Sadly, the NCW’s mouth has refused to comment on the case. Lately, its comments in general have been too often on the side of the status quo. Which leaves women wondering — who needs a National Commission for Men, with an National Commission for Women like this?