World’s Largest Ice Sheet – a ‘Sleeping Giant’ – Is Melting Faster Than Scientists Thought

Two studies, the most comprehensive so far, show in unprecedented detail how Antarctica is changing.

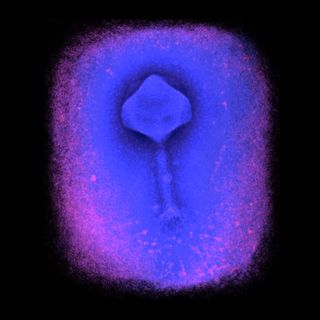

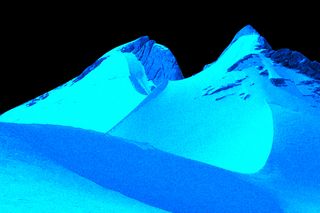

Antarctica is changing in unprecedented ways. But the degree of that change was not understood until now. Satellite images show patterns of worrying change in the East Antarctic ice sheet (EAIS) — the world’s largest block that holds the majority of Earth’s glacier ice. This blanket of ice covers almost 98% of Antarctica and was thought to be largelystable. However, scientists recently found signs of vulnerability; its breathtaking glacial surface is thinning and accelerating the rise of global sea levels. The new analysis doubles the estimate of how much ice Antarctic glaciers have lost over the last 25 years.

“This [East Antarctica] ice sheet is by far the largest on the planet and it’s really important that we do not awaken this sleeping giant,” said Chris Stokes, at Durham University in the UK, who led the study. If EAIS were to melt, globalsea levels would rise by almost 52 meters — almost half the height of the Statue of Liberty.

Stokes, along with researchers from the U.S., U.K., France, and Australia, have documented this slow awakening. They published two studies, the most comprehensive so far, to highlight how this ice sheet and Antarctica are both changing. And if global heating is not limited to 2C — if human-inducted climate crisis increases global temperatures — the ice sheet melting could raise sea levels alarmingly. “Vast areas of East Antarctica remain understudied, including the most vulnerable basins that could contribute to sea level rise over coming centuries.”

Here’s what the two studies tell us. The first one, published in Nature, changes the way scientists estimated ice loss along Antarctica’s cost. They looked at iceberg calving — when ice breaks off from the front of a glacier — and found the calving was happening at a pace faster than they realized. The sheet was losing ice faster than it could replenish. So while previously the belief was that Antarctica’s float ice shelves have lost six trillion metric tons of ice, factoring in iceberg calving drastically revised this estimate: Antarctica glaciers had lost almost 12 trillion metric tons of ice. The ice shelf was weakening outside everyone’s notice.

The second study published in Earth System Science Data further explored how the thinning of Antarctic Ice on the eastern sheet influenced the continent’s other parts, such as the West Antarctica ice sheet (WAIS).

Earlier last year, scientists noted that the Thwaites glacier that resides in the WAIS — also called the “doomsday” glacier — had already lost much of its ice shelf and a total loss would lead to an almost five meters increase in sea levels. To put this into context: the WAIS dwarfs in comparison to its eastern counterpart.

Alarmed at the findings then, the researchers expressed a need for more vigilance in other parts: “Much of East Antarctica is restrained by buttressing ice shelves, so we need to keep an eye on all the ice shelves there.” But as the current analysis reveals, the ice shelves there have undergone massive changes on their own.

Related on The Swaddle:

Geologists Discover New ‘Extremophiles’ in Antarctic Ice Shelf

“We used to think ice sheets in East Antarctica were much less vulnerable to climate change, compared to West Antarctica or Greenland, but we now know there are some areas already showing signs of ice loss,” Stokes said. His co-researcher, Nerilie Abram, added: “It isn’t as stable and protected as we once thought.”

The story of sea level rise is one that scientists and researchers have kept a close eye on. In July, 18 billion tons of Greenland’s ice sheet melted over three days due to rising temperatures, an “unusually extensive” impact that rose sea levels. When the Conger ice shelf in East Antarctica collapsed in March, experts called it “a sign of what might be coming”. Another glacier collapsed in Italy last month.

We already know the sea level is rising faster today than it ever has in the last 3,000 years, and research has shown that glacial melt has driven much of this increase. Water as it changes from ice to liquidcan effectively change land — jeopardizing the safety, homes, and lives of people in coastal cities like Mumbai.

This makes the silent changes in the Antarctican ice sheet more somber. But the analysis reaffirms what people and nations can do to cope with the pace. The 2015 Paris climate agreement urges nations to keep the global heating below 2C; if this continues, EAIS’s melt would be easier to manage as it would contribute less than 0.5 m of sea level rise by 2300. This is the best-case scenario.

The worst? High carbon emissions that surpass the limit can inundate cities — causing up to three meters of sea level rise by 2300 and five meters by 2500. “The fate of the EAIS remains very much in our hands,” the study noted.

Andrew Mackintosh, at Monash University, Australia, who was not part of the study team, said: Society needs to understand that one of the largest potential impacts of global warming – the widespread loss of ice from East Antarctica – is possible if climate warming exceeds about 2C.”

The current findings show us how sensitive EAIS is to rising temperatures, and what this added vulnerability could mean for sea level threats globally. This data “may bring us closer to the big breakthroughs we need to better understand our planet, and to help prepare us for the future impacts of climate change.”

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Celebrities Need to Disclose NFT Ownership Before Endorsing Them, Says Advertising Body