All the Arguments You Need: to Convince People Protests Work

Protests are a tangible, unignorable, unified statement from masses of people that oppression won’t be tolerated.

In our All the Arguments You Need series, we take on mindsets standing in the way of progress and rebut them with facts and logic.

To protest is to exercise a constitutionally guaranteed democratic right. History shows protests are one of the few ways an oppressed, often helpless population can raise its voice in dissent against people in power, letting them know it’s unhappy with the status quo. Protest is a political tool that encapsulates a wide range, from peaceful protests and sit-ins to loud, vocal demonstrations that often result in clashes with law enforcement.

For more than a month now, Indians have been engaging in one of the most powerful, widespread protests the country has ever seen. Students across the country are following the example of Jamia Millia Islamia University and Jawarharlal Nehru University students; women throughout the nation are emulating the Shaheen Bagh women carrying out a more than a month-long sit-in in Delhi, and people are occupying public spaces near major landmarks in their cities to rise up against what they’re calling fascist policies of the current administration — the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA).

Setting aside ideological differences regarding the NRC-CAA, supporters of the policies and apolitical people are critiquing the nature of protest itself. Here are their anti-protest arguments — and why these arguments don’t hold water:

Protests don’t bring about any change.

The process of dissent, especially against an administration in power, is not a sprint; it’s a marathon. Protests will not automatically or immediately lead to a change or revocation of oppressive policies — they’re the first step toward mobilizing the masses and making clear the demands of a movement. This provides the impetus for activists to appeal to political representatives and start a dialogue regarding compromises and changes in existing policies. Protests don’t create immediate change, but without them, change would be impossible.

Related on The Swaddle:

Why Indian Women Protesters Sang a Chilean Anti-Rape Anthem

Examples in history prove this point: the Women’s Suffrage Parade in the U.S. in 1913, when 8,000 women marched for the right to vote, kickstarted a suffrage movement that ultimately led to women enjoying the right to elect their representatives; Mahatma Gandhi’s Salt March in 1930 became a key event in a larger civil disobedience movement that ultimately contributed to India gaining independence from British colonial rule. Today, with the continuous wave of anti-NRC-CAA protests across India, which have also taken the form of petitions to the Supreme Court challenging these policies, a hearing to address protesters’ concerns has been scheduled in February.

Ultimately, protests are a tool to let those in power know their oppressive policies won’t fly anymore, that the citizenry is paying attention and is not afraid to voice their disagreement loudly, and to reiterate that those who elected the politicians also have the power to demote them.

Protests are just an echo chamber for people with the same beliefs to come and vent.

Yes, protesters would largely have the same beliefs regarding the main cause or demand they’re fighting for, and many of their expressions of dissent might even come across as venting, but that doesn’t mean the dissent is not valid. Protests as widespread as those currently occurring in India — with high and diverse participation — have and will make space for a variety of intersectional concerns, wherein all are valid and necessary to effect sweeping change. Within the NRC-CAA protests, for example, protesters have created spaces for transgender people who are uniquely at risk to voice their dissent; the women at Shaheen Bagh have voiced concerns for women’s unique plight under the NRC, keeping their flight intersectional across class and caste lines; students across the country have included police brutality and the saffronization of India’s universities under the larger ambit.

The use of the Internet, specifically social media, as a mobilizing and educational machine has become paramount to mustering support in a movement — be it informing people about the perils of oppressive policies or convincing them to show up. The democratization of digital spaces, in the form of increasing access to social media, has, to an extent, dissolved the echo chamber commonly associated with protest spaces.

Protests are for privileged people with no jobs.

Protests are inconvenient. To effect change at a macro-political level, protesters will have to be inconvenienced. It’s easier for those working white-collar jobs to brave this inconvenience — say, show up at a protest at 2 p.m. on a Wednesday — than it is for those coming from working-class backgrounds who exist in much stricter workspaces that offer fewer opportunities to express themselves. But protests have always existed to challenge the status quo, and they have needed people — from all kinds of backgrounds — to set everything aside to do so. It’s often the most oppressed people in society who will need to come out and protest because the status quo hurts them the most — and they have, and will do so until their constitutional rights are guaranteed.

Look at Shaheen Bagh for example: Muslim women and men from working-class backgrounds, many of them daily wage laborers, have left home and hearth to carry out a sit-in for almost a month. Similar protests have been carried out across the country by people coming from similar backgrounds — because they decided enough was enough. No privileged elite posturing for social media to pass the time. When there is a threat to life and livelihood, as posed by the NRC-CAA, convenience cannot be a consideration — proving protests are not just for the privileged.

Protests hamper the efforts of those in power to do better.

Protests occur when ample chances have been given to those in power to do better; they occur when oppressive situations seem helpless to those involved. Where there is smoke, there is always a fire. It takes a lot to come out and protest — overcoming inconvenience, police brutality, mental health issues. Lakhs and crores of people across the country are not overcoming these hurdles for kicks; they’re showing up because they feel disadvantaged and threatened by the government, because they feel hopeless and faithless in the ‘Hindu Rashtra,’ because they’ve been driven to the streets and made to feel unwelcome in their own country.

Protests signal the populace has lost faith in those in power, that they think it’s better to take matters into their own hands. Protests mean the only avenue left to seek help from is the Constitution because all the branches of government (in most cases) have let the citizenry down. In times like these, it’s imperative those in power listen to protesters, not negate or try to devalue their chosen method of trying to make themselves heard. Protests exist to wake people up; they wouldn’t happen if people weren’t sleeping in the first place.

Related on The Swaddle:

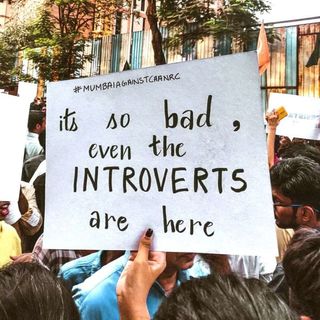

How Anti-NRC-CAA Humor Can Work as a Tool of Political Resistance

In a class- and caste-based hierarchical society such as India’s, it may seem like things are fine when seen through the lens of religion, class, and caste privilege. But diving into minority communities, who have been severely overlooked and taken advantage of by the government, it becomes clear things are far from fine — and it is for them that protesters are taking to the streets in solidarity.

The need of the hour is to speak up, to show up, and to commit to a long, possibly grueling fight for the minority communities of India — a nation that supposedly prides itself for its diversity. Results will not manifest immediately, but it’s imperative to remember that every protest counts, everybody matters. At the end of the day, a dissenting population invested in improving the country is better than a complacent population that doesn’t care.

Rajvi Desai is The Swaddle's Culture Editor. After graduating from NYU as a Journalism and Politics major, she covered breaking news and politics in New York City, and dabbled in design and entertainment journalism. Back in the homeland, she's interested in tackling beauty, sports, politics and human rights in her gender-focused writing, while also co-managing The Swaddle Team's podcast, Respectfully Disagree.

Related

Why It’s Still Legal For Indian Men to Rape Their Wives