'All We Imagine as Light' Tells the Difficult Truth About Mumbai

Most cinematic portrayals of the city romanticize the spirit of Mumbai. Payal Kapadia's film questions that.

‘Once I promised you an epic

And now you have robbed me

You have reduced me to rubble

This concerto ends.’

- Dilip Chitre, Ode to Bombay.

Whenever I describe what Mumbai feels like to me, I frame it with the same fervent gusto that we all have known in popular cinema. She is a supercut of mammoth proportions, a blockbuster film, with drama, delight, devastation. I am talking about the Mumbai that Wake Up Sid’s characters know – one that shakes the young into action and makes room for their coming of age. The city that Gully Boy’s Murad knows – one that, despite the insurmountable divide, lets you climb over it through grit and gutting struggle. The city that is everyone’s jaan, immortalised in song by Mohammed Rafi, and that repeatedly plays stage to unlikely, yet cosmic romances. Everyone knows me as a Bombay romantic with no apologies to make for it.

Since I’ve moved to Melbourne, I’ve missed Mumbai with a deafening ache. It is in my bones, more so than any other city I have lived in. But watching Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine As Light made me realise that the Mumbai of cinema isn’t the Mumbai I actually lived through.

It’s not the tinsel-town version that comes to me today. I catch myself playing the slow jazz that poured into Mumbai’s streets as I walked home. I brood over photo archives and memories, lit in tungsten yellow. I slip in and out of chores to meet this version of me that did all the life-making in Mumbai before here. It is the plodding, beseechingly meditative Mumbai I miss. These moments in the city – they are not filled with debilitating despair or shattering – but a slow, laboured becoming. What all the celluloid recreations of Mumbai often frame as the price that must be paid. I felt like it was essential to making my dreams come true. That was until I watched All We Imagine As Light.

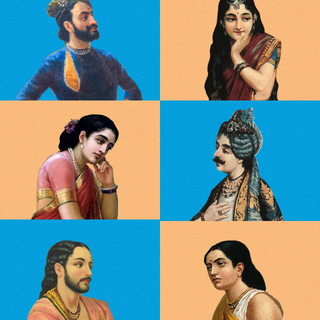

The Cannes Grand Prix-winning film is a delicate love letter to the kinship between Prabha (Kani Kusruti), Anu (Divya Prabha), and Parvathy (Chhaya Kadam). Amidst its characters sits Mumbai – the stage on which these women orbit around each other in caring, sometimes wounding ways. Anu, Parvathy, and Prabha live in Mumbai, but come from different places. Three women, making the city tick in their own ways. Whether you call them migrants or not, to me, they are Mumbaikars in the truest sense – destiny-making in this mammoth, occupying metropolis. Their lives are entangled in the ways I have experienced too. It feels like there is no other world they could have met in, no other city that could have given them the kind of closeness or conflict with each other than Mumbai.

The movie opens with a montage of voices, speaking the many languages that make Mumbai. They talk about their dreams against languorous scenes of the city’s local trains and less shiny stretches. These, unlike the many shots of Marine Drive, or the montages of superstar-fueled glory are the only emblematic elements of Mumbai that make up its portrayal in the film. And they are so potent, I wonder why we ever needed anything else to begin with.

There also isn’t a single moment of intimacy without the city playing spoilsport to Anu's and Shiaz's desire.

At the very outset, All We Imagine as Light, shows how the mythos of the Mumbai Dream isn’t just woven into just pop culture, and in the ways that its people interact with each other, but also within the physical city itself. Take, for example, how the Statue of Progress rises above Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus and Flora Fountain, looking down at the swathes of crowds, promising abundance. Or how voluminous tomes are written in ode to the messiness of the city, which collectively comprise the genre of ‘Bombay lit.’ Or how, even, thousands of Instagram reels picturize Mumbai sunsets and vada pav vendors set to quaint indie music. Despite myself, Mumbai is permanently inscribed on my body in the form of two tattoos. Mumbai has always known that optics are everything.

On the other hand, the film depicts the city in damp blue – to signify impermanence; or the fact that any structure covered in the blue tarpaulin is bound to be replaced by something shinier, as Kapadia explains. Shiny skyscrapers only in soft backgrounds, and the interior spaces, often cracked and dimly lit. The materiality of the city is mostly only its people and their desires, set to train montages. It speaks to how the local trains have always functioned as a great equaliser in Mumbai, whether its residents like it or not. It’s hard to completely barrier your personhood from everybody else on a train with you – paying the same dues you are. “You’d never fight with people back home the way you would in the ladies compartment; you’d also never strike up a conversation with them like you would anywhere else,” says Kimberly Anthoney, an advertising professional who moved here in 2017. “It’s because there is a quiet understanding here. We all have been given this chance, this luxury to be here, in Mumbai – free of the people that we were back home. Anonymity means autonomy to Mumbai’s women.”

Like it has to millions before me, Mumbai gave me a sense of abandon and security at once. But as is the case with most things, if you are not paying the price, someone else is.

It is this anonymity that affords Anu her tender romance with Shiaz. The onerous yearning they have for each other unfolds with caution. They need not be reminded of the consequences that come with a young Hindu girl desiring a Muslim boy. In their bursts of abandon, they embrace and kiss in Mumbai’s panoptic corners. But there also isn’t a single moment of intimacy without the city playing spoilsport to their desire. The film explores Mumbai’s paucity of space – something that everyone who lives there is constantly reminded of. Prabha doesn’t even get any to properly grieve her estranged husband in the apartment she shares with Anu.

“It is the same fight I see everyday, just to feel defeated by the end of it … Space – physical, emotional, existential – is constantly out of reach,” says Ninad who moved to Mumbai from Manipur. “I can’t deny what the city does give me though. Coming from a place of constant conflict, Mumbai offers safety, and it’s shaped my personality and worldview in ways I can’t imagine elsewhere.” they add.

As someone who doesn’t conform in very many ways, gender expression largely, I resonate with this greatly. Like it has to millions before me, Mumbai gave me a sense of abandon and security at once. But as is the case with most things, if you are not paying the price, someone else is. In the case of Mumbai, it is the working class that builds the city to what it prides itself on – a safe metropolis. But who gets to enjoy the same safety that the city is famed for? Where do the wronged go if they have no homes, even?

They leave. Like Parvathy in the movie – who lived in Mumbai long enough to become one with the city. One day, she loses her house to the builder nexus and “redevelopment.” Decades of her life come undone. All she has to show is boxes of what Anu calls “junk.” No fancy lawyer, no revolutionary unions, and no fighting spirit can save her from the fate many face. Without paperwork to prove it, you’d feel like you’re not a real person these days, she says. This was an especially powerful moment that speaks to the countless residents of the city who have lost homes and lives to the pursuits of the city. It feels unreal, and Parvathy says so – the city is an illusion.

In its meditative sequences, All We Imagine As Light questions the Spirit of Mumbai, its deceptive nature. Mayanagari.

“What is the relation of Dalits, Muslims, Adivasis and other minorities to the city that they make? If the people that historically built Mumbai view it as an illusion, what do you make of it?” asks Shripad Sinnakaar, an anti-caste poet. “Mumbai decides your legitimacy as a citizen. Take the context of Adani’s takeover of Dharavi, the evacuation of Air India colony in Kalina, or the demolition of Jai Bhim Nagar. Mumbai’s people have always had to prove their worth through documents. Their history of migration, their life – all of it reduced to bureaucratic regimes to survive.”

In its meditative sequences, All We Imagine As Light questions the Spirit of Mumbai, its deceptive nature. Mayanagari. In a lot of other portrayals, the struggle of Mumbai’s residents acts as a catalyst. Mumbai rewards the hustlers. The typical love letter to the city acknowledges its harshness but also excuses it. Like in Gully Boy, or Wake Up Sid’s Aisha, or even Slumdog Millionaire – you walk away from the depictions of Mumbai feeling like you only have to try that little bit harder to get where you must. Struggle is a stepping stone, not something you eventually submit to.

The desires that Anu, Prabha and Parvathy have are so different, but they are connected by the truth that they don’t get realised. In Mumbai, however, where you’re replaceable more than valuable, most of its residents continue to cling to these cruelties.

“This city draws everyone in with the promise of opportunity. Maybe that’s why we cling to the idea that struggle is noble – each day here feels like an achievement. It’s easy to romanticise survival because Mumbai makes it feel like it is a choice, not a necessity. I’m increasingly unsure if that’s how it’s meant to be,” says Natasha Kavalakkat, a lawyer who lives in Mumbai but is considering a move.

Moving away from the city changes the fates of Prabha, Anu, and Parvathy too. On their trip to coastal Maharashtra, they find what they were seeking. Their dreams were made in Mumbai but come true far, far away from there. And like Prabha, Parvathy, and Anu, it rings true for me too, as I write this in Melbourne. I am here, living a reality I imagined I would bring to light in Mumbai. What movies in Bollywood told me I would find after persevering, persisting, and giving it my all. Perhaps it does for a few, but who are they, and at what cost do they get there? If you are amongst the many that Mumbai wounded, it is simple – you take what Mumbai gave you, or takes from you, and move on. Mumbai moves on.

Parth is a poet and writer currently based in Melbourne. Parth's work has been featured across stages, galleries and publications in India and the world—including the ISCP, New York, The narrm ngarrgu Library, The Brighton Centre of Contemporary Art, Vogue India, and ASAP Art amongst others.

Related

The Price of Friendship With a ‘Good Man’