Almost 1 Billion People With Physical Disabilities Lack Access to Assistive Aids, Finds Global Study

Denying people access to these “life-changing tools” infringes on human rights and leaves them vulnerable to exploitation.

The first global report on assistive technology — such as wheelchairs, hearing aids, or apps — presents a chasm familiar but daunting in its depth. Globally, more than 2.5 billion people with disabilities need one or more assistive products to support their mobilityand cognitive needs. Yet, nearly one billion people do not have access to these aids. Like every disparity, this gap is more pronounced in low- and middle-income countries; experts note that access to these aids could be as low as 3% in poorer countries as compared to 90% in wealthier countries.

To put these figures in perspective: a bulk of the global population living with a disability does not have access to an assistive aid that would improve their quality of life.

“Assistive technology is a life changer – it opens the door to education for children with impairments, employment and social interaction for adults living with disabilities, and an independent life of dignity for older persons,” said World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. The said technology doesn’t only refer to physical products such as prosthetics or spectacles, but also investing in making our physical spaces more accessible — like setting portable ramps.

The report, titled The Global Report on Assistive Technology, details the findings examining the degree of support offered across 35 countries and includes recommendations by both WHO and UNICEF. The gap in the infrastructure of care is for the first time identified and quantified. The provision of assisted aid, what Dr. Tedros calls “life-changing tools,” is a matter of dignity and human rights.

This could be for two reasons. One, the number of people who would need one or more assistive aids is likely to increase by 2050 — a jump from 2.5 billion to almost 3.5 billion. This could be attributed to the rise in non-communicable diseases globally. This makes the availability, safety, effectiveness, and affordability of assistive products a matter of fundamental rights that deserves greater advocacy. “Denying people access to these life-changing tools is not only an infringement of human rights, it’s economically shortsighted,” Dr. Tedros added. The rationale here is self-evident: safe and affordable assistive products reduce the overall health and welfare costs people and the state take.

Two, the absence of assistive products not only hinders community integration, but proves exclusionary and discriminatory. As the report noted: “…children with disabilities will continue to miss out on their education, continue to be at a greater risk of child labor and continue to be subjected to stigma and discrimination, undermining their confidence and wellbeing.” Disabled people may be subject to more labor exploitation without access to assistive tech.

Related on The Swaddle:

Why We Expect People With Invisible Disabilities To Learn To Act ‘Normal’

There remain multiple barriers to integrating assisting aids with the built environment as well as individual lifestyles. Lack of public health messaging and awareness, unaffordable prices, poor quality, and limited supply are some of them.

To meaningfully engage with the needs, a country has to develop a national assistive products list that takes into account the holistic needs of the population, the product costs, and benefits. How does India fare among all of this? According to the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) Report on Disability 2018, only 23.8% of persons with locomotor disability, 31.5% of persons with visual impairment, and 19.1% of persons with hearing impairment have accessed one. And out of those who have access to devices, only 5-9% of beneficiaries have done so through government programs. Which would mean that the needs of more than 70% of the population in need of assistive aids are overlooked and unmet.

“Disadvantaged groups and communities face hardships in their search for affordable quality healthcare in India and that for obtaining AT and associated services is no different… Products are often sub-standard and lead to poorer health outcomes,” the Financial Express noted. By sub-standards, experts note how the products are one-size-fits-all, and not customizable to the specific needs.

Even India’s police and programs towards those living with disabilities are built on flimsy scaffolding, experts note. Nipun Malhotra, co-founder and CEO of Nipman Foundation and founder, Wheels For Life, told NDTV how most schemes (like the Scheme Of Assistance To Disabled Persons For Purchase/Fitting Of Aids/Appliances) are based on cash transfers and include people living under the poverty line as said beneficiaries of these schemes only. So, for instance, under the ADIP Scheme, the government will cover the full cost of the aid for a person living with a disability whose monthly income is less than Rs. 6,000. This insistence on cash transfers leaves out a major subset of the population. “This is extremely problematic because all the persons with disabilities have to incur higher costs of living as compared to any other person with the same economic background. The standard of living of the families with persons with disabilities will always be lower than others,” he noted.

The Indian government also levies a 5% tax on disability assistive devices such as crutches, wheelchairs, walking frames, tricycles, braille watches, and many other items. This inevitably increases the price of products and further restricts people’s communication and movement.

Among the 10 recommendations the report offers, the need to increase public awareness, combat stigma, and improve access within education, health, and social care systems underlines the social benefits of countriesinvesting in affordable AT.

It is a matter of public health and personal dignity to have access to assistive aid without being embroiled in financial difficulties. Only in February this year, activists urged the Tamil Nadu government to increase the monthly assistance amount from the current Rs. 1,000. Keeping in mind the medical needs of people with disabilities, along with daily requirements, the compensation grievously falls short in recognizing the lived realities of thousands of people.

In recent years, activists have also moved to expand the scope of what “disability” means; advocating for invisible disabilities to be spoken about and responded to with care and consideration. “When it comes to invisible disabilities like autism, people are expected to somehow learn the ropes of a so-called ‘normal’ lifestyle,” Devrupa Rakshit wrote in The Swaddle last year. “So, despite autism being considered a disability in various parts of the world, including India, the needs of autistic individuals are rarely recognized within education systems and workplace cultures, both of which are still designed with neurotypical people in mind.” There lies an urgent need to rethink accessibility beyond physical AT in itself.

For now, a more self-sustaining model, experts note the health aspect of care will help bridge the deficiencies. While effort remains to produce good quality, affordable aids, the focus can also be on placing rehabilitation at primary health-care levels. This could pave way for long-term care and even promote a rehabilitation model that is community-led.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

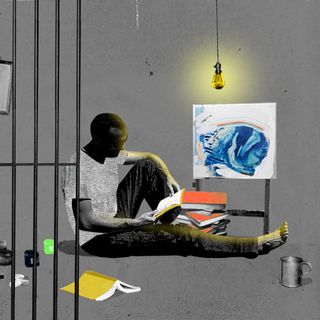

How Books, Literature Can Support Indian Prisoners’ Rehabilitation