An Optical Illusion Can Help Researchers Better Understand Our Brains

The “expanding hole” illusion holds many lessons for researchers, showing that optical illusions aren’t always gimmicks.

The black holes of nature are among the most perfect objects to exist. They are also the most terrifying; falling through a black hole is the subject of many theories and fictional narratives. It could be like falling through a rabbit hole, but there is quite possibly no way to know the secrets trapped within these objects of vacuity. Now imagine the dizzying prospect of a black hole swallowing you whole.

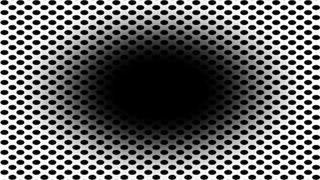

This is an experience that has newly surfaced in the corridors of the internet. The “expanding hole” illusion has dark, black ellipses spotting a white background; at the center is a big circle. To the eye, it feels like the black ellipses are slowly getting bigger and bigger, creating the illusion of the person falling into the black hole at the center of the image. According to a new study published in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, as many as 86% of participants seem to fall for it. The black hole illusion is quite adept at deceiving the brain.

It is easy to dismiss this as a parlor trick — one of the many illusions and simulations we can amuse ourselves with. Stare long enough at anything and it has the potential to disorient the person; think the never-ending Penrose Stairs, or the Ames Room Illusion (when one person on the side appears much taller than they really are) that was also used quite freely in Lord of the Rings editing.

Yet, the “expanding hole” illusion holds many lessons for researchers, lessons that could be quite instructive in how we understand the way eyes — and our brain — function.

“The ‘expanding hole’ is a highly dynamic illusion,” Bruno Laeng, a professor at the department of psychology of the University of Oslo and first author of the study, said in a statement. To test just why and how people seem to be falling prey to it, Laeng, along with others, measured the pupillary response of 50 men and women with “normal” vision to see how the illusion played out physiologically.

“The circular smear or shadow gradient of the central black hole evokes a marked impression of optic flow, as if the observer were heading forward into a hole or tunnel,” Laeng explained. The pupil expanded when looking at the black ellipses, because to the brain, it was almost as if the person was physically moving towards an area that was darker than their current surroundings. To compensate for it, the brain responded (even if preemptively) by adjusting the eyes to glean more light from the surroundings.

What explains the illusion of moving forward, though? The black blob’s soft edges create the appearance of a motion blur. “That’s why observers see the black blob as growing, the same thing one would see when walking towards a dark cave, for example,” Andrew Liszewski explained in Gizmodo.

In other words, the pupils did dilate, or increase in diameter, in response to the illusion — even if the body was aware that the pupils are being tricked. It didn’t matter how real or illusory this was, the eyes responded as if they were viewing a black hole legitimately expanding.

Related on The Swaddle:

This goes to show just how much imagination is at play — a line of inquiry that goes beyond just hearing or listening about this trick from other people. Instead, the illusion has much to do with a physiological index at large: the eye is adjusting to a perceived, even imaginary, light — not a tangible and physical energy. Our pupils dilate in the very anticipation of entering a dark space.

The researchers also experimented with different colors of the illusion: ellipses bearing the colors blue, green, cyan, magenta, yellow, red, and white holes were shown to the participants instead of the standard black ones. Even then, the pupils reacted in response to the illusion — but the response was weaker in comparison to how the eye reacted to dark objects. For the 86% of participants who saw the illusion, the darkness prompted dilation, while colored versions meant people’s pupils contracted and got smaller in diameter.

This again confirmed that an illusion is potent enough to cause a physiological response. The link between pupil dilation and illusion is noted before. “While it was already known that imagined objects can evoke so-called ‘endogenous’ changes in pupil size, we were surprised to see more dramatic changes in those reporting more vivid imagery,” one researcher said. A separate study also noted that pupil dilation in and of itself could indicate if someone experiences aphantasia — an ability to picture objects in the mind without visually seeing them.

“Even if you didn’t say you saw the illusion moving before you, your eyes may be silently giving you away — and this realization is arguably more evidence that we might want to rethink the scientific value of our tiny optical voids,” notes an article on CNET.

The present value of the research lies in showing how not all optical illusions are gimmicks meant for light amusement. The study’s future, then, will look into other biological reflexes to such visual optics; eventually, researchers hope to know more about how people physiologically experience illusions.

It is a matter of conjecture where we would emerge if we were to plunge down a black hole. Some would say we may re-emerge in a different part of the universe. A more realistic answer is we could get torn apart by extreme gravity. While scientists wonder and re-wonder, there is comfort in finding an internet black hole that isn’t wholly menacing — even if it’s a trick.

Image credits: Laeng, Nabil, and Kitaoka.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

What Colors Do Animals See?