Ancient Indian Caves Hold a Record of Historical Droughts across Asia

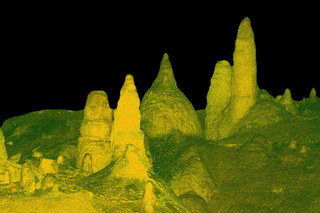

The current geological age is dubbed ‘The Meghalayan Age’ after the location of the caves. Stalagmites found here can help us figure out when to expect another drought.

The world’s wettest place holds records of its dryest spells.

In a study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, scientists observed how stalagmites — towers of calcium carbonate shaped over thousands of years from sediment deposits in rainwater — in caves in the northeastern state of Meghalaya can help study the history of monsoons in the Indian subcontinent across the millennium. The study is significant: as though sealed in amber, the record of monsoons etched into the ancient rocks provides earlier unknown information about long droughts and other cataclysmic events in the region — ones that killed millions of people, and could well do so again.

The limestone caves of Meghalaya formed over millennia — and their relationship with droughts — have been in the limelight in the last few years due to their geological and historical significance. In June 2018, the International Commission on Stratigraphy, the governing body on stratigraphic and geological matters, marked the current geological period as the “Meghalayan Age.” The Commission declared that the Meghalayan Age began 4200 years ago with a 200-year-long drought that impacted several human civilizations, including the Indus Valley Civilization in South Asia and the Yangtze River Civilization in China. The evidence of this long drought is recorded in the stalagmitic formations — in Meghalayan caves, hence the name.

In the current study, researchers considered similar stalagmitic formations in the Mawmluh cave near Cherrapunji in Meghalaya to go back in time: investigating monsoons in the subcontinent over the last thousand years.

On drawing up the data of monsoons over the millennium based on these parameters, scientists found some worrying records that policy researchers and weather scientists have overlooked. In a press release, they explained that since the 1870s, India has seen only one prolonged nationwide drought. This sounds like good news, but it isn’t so simple. Studying the limited period of 150 years of Indian monsoon suggests that it is stable and sure to occur every year, and that frequent and long-lasting droughts in the subcontinent are, at best, an anomaly. This reliance on the presumed stability of the Indian monsoon dictates how governments plan present-day management of water resources — without accounting for any possibility of drought or scarcity. “However, the stalagmite evidence of prolonged, severe droughts over the past 1,000 years paints a different picture.” In other words, we might be complacent in our resource planning, and might be sitting on a ticking time bomb we were never prepared for.

Related on The Swaddle:

In Meghalaya, the Umngot River Keeps Tribal Livelihoods Afloat. A Dam Project Threatens That Balance

The scientists considered two ratios to determine how the quality and character of monsoons changed over the years. One value they considered was the ratio of uranium — a primary element that is collected in stalagmite deposits in Meghalaya — to thorium — the element that uranium decays into over a period of time. The other value they considered was the ratio of different oxygen isotopes carried by the rainwater that varies according to prevailing climatic conditions.

Differences in uranium-thorium ratios in every layer of the stalagmites helped scientists calculate the time period of that layer’s formation, while oxygen isotope ratios in those layers helped them estimate the quality and character of the monsoon during the said period.

There’s another link between droughts and civilizations that the mystical rocks reveal. The researchers further note that their estimates for drought periods were remarkably congruent with historical documentation of famines, mass mortality events, and geopolitical changes in the region. For instance, they mention, “the decline of the Mughal Empire and India’s textile industries in the 1780s and 1790s coincided with the most severe 30-year period of drought over the millennium.” Similarly, “another long drought encompasses the 1630-1632 Deccan famine, one of the most devastating droughts n India’s history. Millions of people died as crops failed. Around the same time, the elaborate Mughal capital of Fatehpur Sikri was abandoned and the Guge Kingdom collapsed in western Tibet.”

These findings indicate that the researchers’ calculation of drought periods based on studying layers in stalagmites can be a reliable method to analyze monsoon profiles systematically and scientifically over long periods of time, including for periods when documentation was not common or did not cover as much territory as today’s nation-states.

This is significant as looking at the monsoon profile over a longer period, and understanding how climatic events played a role in them — such as influencing the source of moisture for monsoon winds — can help guide better planning and policies vis-a-vis allocating water and other resources to people. As the above incidents indicate, events like droughts and floods can influence geopolitical change and affect stability, hence awareness of the possibility of such events and stable policies to mitigate their effects can also help save lives and livelihoods. As the world finds itself in the middle of an ongoing climate crisis, it is vital that policies are designed to address every contingency.

Stalagmites, like tree rings and Himalayan ice cores, can serve an important purpose in decoding the earth’s conditions over huge swathes of time. An earlier study of Meghalayan stalagmite formations over a relatively smaller timeframe — 50 years — had shown how there were connections between winter rainfall patterns in the Northeast and the climatic conditions in the Pacific. They thus can be a vital source for studying the climate, and perhaps also determining how it may change in the future.

There’s one limitation to the study’s current approach of looking at stalagmites and other natural structures for climate records. They note that “paleoclimate records can usually tell what, where and when something happened. But often, they alone cannot answer why or how something happened. Our new study shows that protracted droughts frequently occurred during the past millennia, but we do not have a good understanding of why the monsoon failed in those years.” They mention that following their findings on stalagmitic records, they intend to team up with climate modelers to examine what climatic triggers led to situations of droughts and famines in the first place.

Amlan Sarkar is a staff writer at TheSwaddle. He writes about the intersection between pop culture and politics. You can reach him on Instagram @amlansarkr.

Related

The Many Ways Fossil Fuel Companies Are Using Social Media to Greenwash Climate Inaction