Why People Are Not Getting Better at Recognizing Masked Faces

“[F]ace processing in humans — at least in adults — is rigid even after prolonged real-life exposure to partially covered faces.”

The other day, I felt a small tinge of disappointment when a business owner couldn’t recognize me — a loyal, long-term customer who had been visiting his savory shop since childhood. At one point, he even knew exactly which product I was there to buy, and the special request I’d always make for it. “How could he possibly have forgotten my face?” I asked my partner. He pointed out that I was wearing a mask; a fact I’d totally overlooked now made complete sense.

In 2020, science journalist Elizabeth Preston had written in The New York Times: “In an era of face masks, we’re all a little more face blind.”

One would assume that constantly witnessing covered faces would change our ability to recognize them better — that, arguably, after more than two-and-a-half years of co-existing with the once novel coronavirus, people should have been able to circumvent, or gotten accustomed, to this blindness of sorts.

Yet, it is as hard as ever to recognize people behind masks. Published last week in the journal Psychological Science, a new study explains why.

“Neither time nor experience with masked faces changed or improved the face mask effect. This tells us that the adult brain [does] not seem to have the ability to change how it processes faces, even when presented with masked faces over an extended period of time,” concluded its lead author Erez Freud, an assistant professor in the psychology department at York University’s Faculty of Health. Explaining further, Freud noted, “[F]ace processing in humans, at least in adults, is rigid even after prolonged real-life exposure to partially covered faces.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Why We See ‘Human Faces’ in Objects Sometimes

An earlier study, published in Scientific Reports in December 2020, found that the adult participants’ experienced a 15% reduction in their ability to recognize faces that were partially covered by masks.

To confirm whether the struggle persists, the researchers behind the present study tested the facial recognition abilities of more than 2,000 participants through a series of assessments. Then, they tested the same group of participants twice with a gap of 12 months in between, to see if repeated, long-term exposure to masked faces made a difference. There was no improvement, they noticed.

With masking not entirely being a thing of the past yet, the inability of the human brain to improve its facial recognition skills is concerning. “We use face recognition in every aspect of our social interaction. This is something very fundamental to our perception. And suddenly, faces do not look the same,” Freud had told Preston earlier.

However, not everyone might be equally unskilled at recognizing masked faces. Past research suggests that the culture one grew up in might also impact how one’s ability to recognize faces fares — for instance, compared to participants from the U.K., participants from Egypt were better at recognizing faces covered by headscarves. Called the “headscarf effect,” the disparity in performance between Egyptian and British participants suggests that as a result of being exposed to a large number of women wearing headscarves as part of their culture, the former set of people may have evolved a better skillset to recognize masked faces.

Preston, then, asked Katsumi Watanabe, a cognitive scientist from Tokyo, whether people in Asian countries who were used to seeing their countrypeople wearing protective masks much before Covid19 hit the world, might also be more skilled at recognizing masked faces. Watanabe noted, “It is indeed an interesting point… Western Caucasian people tend to decode facial expressions based on the mouth region, while Eastern Asian tend to use the information from the eye region.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Why Some People Struggle To Recognize Faces

However, neither the research on Egyptians nor Watanabe’s observation about East Asians necessarily suggest that people’s ability to recognize faces hidden behind masks improves with greater exposure over time. What it does suggest is that those who have grown up in cultures where people around them often tend to cover their faces, might have developed patterns to focus on features like the eyes, the nose bridge, or the shape of one’s eyebrows to recognize people.

That could mean there is hope yet for people from other cultures, who are only now getting used to seeing masked faces around them. But is this something an adult human brain can at all develop, or must one have subconsciously devised alternate focal points since childhood? The answer to that continues to remain elusive.

The answer to that continues to remain elusive. “[W]ould children become better at recognizing masked faces as they gained more experience with such faces? This seems likely because previous research found that children’s brains are more adaptable and that experience can shape their visual abilities,” notes a piece on The Conversation co-authored by Freud and Shayna Rosenbaum, a neuropsychologist and cognitive neuroscientist.

“Sensitivity to faces appears early in life… Despite this early sensitivity, face perception develops slowly, and some studies suggest that this ability is not fully matured even in teenagers.”

Perhaps, the reason adults in the present study showed no improvement in their facial recognition abilities was because their brains had matured fully, and weren’t as malleable as that of children. It’s only future research that can shed more light on the subject.

Devrupa Rakshit is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She is a lawyer by education, a poet by accident, a painter by shaukh, and autistic by birth. You can find her on Instagram @devruparakshit.

Related

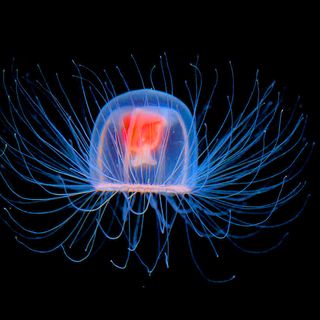

What Jellyfish Can Tell Us About Immortality