Archaeologists Discover the Oldest Evidence of Cooking in Pre‑History

Existing evidence suggests humans started cooking 1,70,000 years ago. The current evidence pushes that timeline by more than 6,00,000 years.

Cooking food is one of the most distinguishable human traits. Humans, indeed, are the only species on earth known to cook their food. It is so ingrained in human life that it today is both a necessary life skill and an art form. And we now have a newer timeline for when humans first began cooking. A team of archaeologists from multiple universities recently discovered an archaeological site in Israel that documents the first-ever use of fire for cooking food, which can help us to better unravel our evolutionary history.

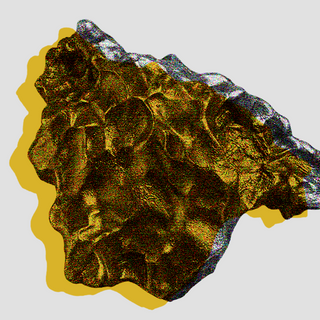

Humans’ knowledge of cooking came from the discovery — and subsequent use — of fire in daily life. However, presently, there exists a huge gap between the first pieces of evidence of the controlled use of fire by humans and that of cooking food. The first traces of fire use — charcoal and burnt bones — date back to at least 1.5 million years ago (mya) at Homo erectus sites in Africa. Cooking with fire, in contrast, is relatively recent, with existing evidence — heated remains of starchy plants, in an underground oven in Africa — dating back to only about 1,70,000 years ago. The findings of the current archaeological study, published this week in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, push this date back by at least 6,00,000 years ago.

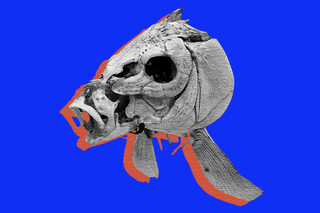

In their expedition, the researchers explored the archaeological site of Gesher Benot Ya’aqov in Israel. They closely examined the cooked remains of a carp-like fish, noticing that they exhibited signs of having been heated in a controlled environment around 7,80,0000 years ago. The scientists noted that the crystal formations in the enamel of the teeth in fish remains of the once-freshwater area sufficiently suggested that they were cooked under a controlled fire. “We do not know exactly how the fish were cooked but given the lack of evidence of exposure to high temperatures, it is clear that they were not cooked directly in fire, and were not thrown into a fire as waste or as material for burning,” Jens Narkoja, a contributing archaeologist to the research, said in a press release on the study.

“These new findings… illustrate prehistoric humans’ ability to control fire in order to cook food, and their understanding the benefits of cooking fish before eating it,” Dr. Irit Zohar and Dr. Marion Prevost, also part of the team of archaeologists behind the discovery, explained. The archaeologists further suggest that cooking food over a controlled fire played a big role in the evolutionary advances of the human species. This adds credibility to the “cooking hypothesis,” a concept first put forward by British primatologist Richard Wrangham in 2009.

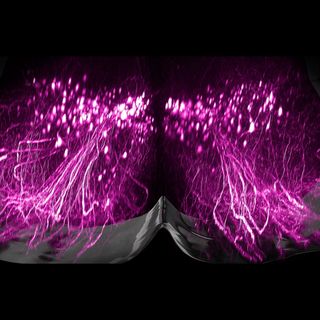

Wrangham argues that “the transformative moment that gave rise to the genus Homo, one of the great transitions in the history of life, stemmed from the control of fire and the advent of cooked meals.” According to Wrangham’s hypothesis, cooking had far-reaching evolutionary effects on humans’ ancestor species, as it allowed them to spend less time foraging, chewing, and digesting food. The Homo erectus developed a smaller digestive tract, and this freed up energy for the growth of a larger brain.

Related on The Swaddle:

We’ve Completely Misunderstood ‘Survival of the Fittest,’ Evolutionary Biologists Say

Wrangham’s hypothesis is often criticized on the count that existing pieces of evidence of cooking only dated back to a period when Homo sapiens had already evolved and replaced their ancestors. The current findings, push the date of the use of fire much closer to Wrangham’s proposed timeline of 2 mya.

The researchers support Wrangham’s arguments on the evolutionary developments that cooking would have facilitated. Additionally, they note that early humans used up the time freed from the arduous processes of foraging and digesting to develop new social and behavioral systems. Naama Goren-Inbar, one of the contributing archaeologists to the research, notes, “Gaining the skill required to cook food marks a significant evolutionary advance, as it provided an additional means for making optimal use of available food resources.”

The researchers also suggest that eating fish, particularly, was a major catalyst in the development of the human brain. Dr. Zohar and Prevost explain, “This study demonstrates the huge importance of fish in the life of prehistoric humans, for their diet and economic stability.” The researchers also note how consuming fish flesh, replete with nutrients such as zinc, iodine, and omega-3 fatty acids, is still recommended for brain growth.

Although the study predominantly was focused on fish remains, Goren-Inbar speculates that “It is even possible that cooking was not limited to fish, but also included various types of animals and plants.” The findings of the study establish a new timeline for the development of cooking food, and further emphasize the role it has had on human evolution. They also suggest that early humans, living in freshwater settlements and learning to cook their food, were much more advanced than we earlier understood them to be.

Amlan Sarkar is a staff writer at TheSwaddle. He writes about the intersection between pop culture and politics. You can reach him on Instagram @amlansarkr.

Related

Researchers Discovered Privilege, Wealth Disparities Among Animals Too