Bed Rest During Pregnancy Is a Common Prescription, But Does It Actually Help?

Doctors say it’s more about risk mitigation than actual treatment.

A second time mom-to-be in her third, and longest, hospital stay, Lisa Lerer wasn’t sick — she was just pregnant. In her piece for The Atlantic, Lerer recounts her tale of being one of the 20% of women prescribed bed rest during pregnancy. Additionally, up to 95% of obstetricians report they’ve prescribed the treatment in some form.

But is bed rest the one-size-fits-all approach for problems during pregnancy?

“That’s the greatest mistake some doctors commit — confuse bed rest with rest,” says Dr Veena Aurangabadwala, obstetrician and gynecologist with Zen Multispeciality Hospital in Chembur, Mumbai. “A pregnant woman needs eight hours of sleep, and an additional two hours in the day if she can fit it in her schedule — not immobility.”

Of any 10 patients she examines, Aurangabadwala says, at most two may end up needing bed rest for one or more of the following complications: recurring miscarriage, high blood pressure, hypertension or a low-lying placenta, a condition when the placenta covers part or all of the cervix during the last months of pregnancy, which can cause severe bleeding before or during labor.

Other symptoms that might prompt a doctor to prescribe bed rest are vaginal bleeding in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy (which could indicate miscarriage), a history of miscarriage, or if a woman is at high-risk of preterm labor, according to Dr Manjiri Mehta, a consultant gynecologist, obstetrician and laparoscopic surgeon with Mumbai’s Hiranandani Hospital.

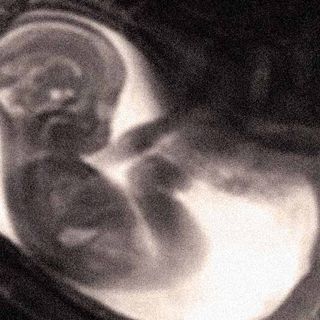

Smita Bammidi, a 36-year-old Mumbai-based assistant professor required bed rest because she went through retro chorionic hemorrhage, when blood pools between the embryo and the uterine wall, in early pregnancy. “We don’t know what caused it, but I was on the bed for three months,” says Bammidi, who was allowed to leave her bed only once a week to see the doctor.

But, it helped her. Now in her seventh month of pregnancy, “I am out of danger, I swim, go for brisk walks, even finish field work for my college assignments,” she adds.

Yet, on a large scale, there’s no proof bed rest actually helps treat complications. As Lerer writes, “The practice continues despite a growing body of medical evidence showing that bed rest offers little to no benefit to pregnant mothers or their fetuses. The treatment has not proved effective in treating preeclampsia, preterm birth, low infant birth weight, high blood pressure or a shortened cervix.”

And bed rest can prompt serious complications itself: It can increase the risk of deep-vein thrombosis — blood clots, usually in the legs, that lead to pain and swelling — and cause constipation, difficulty breathing, backache and muscle pain. It can also exacerbate diabetes, cause bone loss, and atrophy the very muscles women use during childbirth. And then there’s the toll on mental health.

“In some more serious cases, women on bed rest are at a higher risk of depression,” adds Dr Aurangabadwala.

Bammidi wasn’t depressed, but she certainly wasn’t in the best frame of mind during her period of imposed inertia. “I got out only once a week to go to the hospital, and in this period, I was bored, angry about missing out on work. My husband and I had frequent fights,” she says.

Ultimately, “bed rest is seen as the best way to mitigate risks,” Dr Aurangabadwala says — possibly because, as Lerer notes, a near-complete lack of research on pregnant women means clinicians have little evidence-based treatments to offer.

The attitude has spread to patients as well.

“Sometimes the patients and her relatives are very apprehensive or scared about the pregnancy and ask for [bed rest],” says Dr Mohita Goyal, gynecologist at Pune’s Motherhood Hospital. “Most couples are choosing to have babies late, they want just one or a maximum of two, so they want to ensure that nothing goes wrong.”

Shalini, who prefers to be identified by her first name only, didn’t second guess when her gynecologist advised bed rest, without an internal examination or a sonography, after she experienced spotting in the sixth month of her pregnancy. “She told me either my baby won’t survive or that I would have a premature delivery,” says the 33-year-old Mumbai-based journalist. “I stopped going to work, and had to get out of bed only to eat and use the washroom.”

In the days that followed, the spotting stopped. However, “the bed rest was making me restless, even more fatigued and irritable,” she says. “I decided to go for walks and dinners and ended up feeling perfectly fine.” Now in her eighth month, she’s traveling approximately 50 km every day for work and hasn’t experienced any further complications.

Whether or not bed rest actually helps pregnant women isn’t something most doctors and families want to take a chance on. And so, its prescription — and request — will continue, feeding an idea of pregnancy and care that may not be entirely true.

“Pregnancy is a physiological state, not a disease,” Dr. Aurangabdwala says. “Most doctors and patients need to understand [this].”

Anubhuti Matta is an associate editor with The Swaddle. When not at work, she's busy pursuing kathak, reading books on and by women in the Middle East or making dresses out of Indian prints.

Related

Scientists ID Chemicals in the Blood That May Predict Stillbirth