Meet ‘The Blob,’ the Slime Mold That Can Think Without a Brain, Eat Without a Mouth

The Paris Zoo is currently showcasing a yellow, unicellular mold with 720 sexes that can heal itself in minutes.

It’s not a plant, animal or fungus. It has no eyes, no mouth, no stomach — and yet it eats. It has no brain or nervous system — and yet it can solve math problems, find the shortest way out of a labyrinth, and remember stuff. It has a mindboggling 700+ sexes, can heal its wounds in less than two minutes if cut in half, all while being just one giant cell. In other words, it’s way cooler than you (and will probably be the death of all of us).

Meet “The Blob,” a bright yellow slime mold belonging to the kingdom Protista, an ancient group of organisms that have been on Earth millions of years before the first animals appeared. Officially known as Physarum polycephalum or “the many-headed slime,” the unicellular organism is believed to be about a billion years old and is the latest addition to the Paris Zoo’s first-of-a-kind exhibition open to the public since October 12, 2019.

“The Blob is really one of the most extraordinary things on Earth today, but it’s been here for millions of years, and we still don’t really know what it is,” Bruno David, president of the Natural History Museum, of which the Paris Zoological Park is a part, told AFP.

We REALLY don’t know what it is

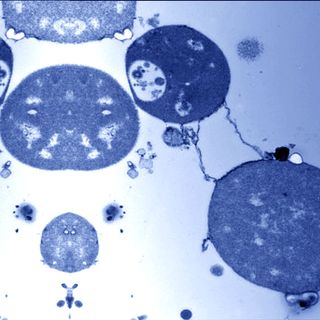

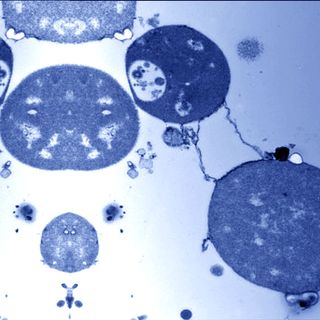

So, here’s what we know. Physarum polycephalum is amoeba-like, looks like a fungus but isn’t one, thinks and reasons like an animal with a brain but isn’t one; Physarum polycephalum is an entirely separate branch in the tree of life. Unlike most cells, which only have one nucleus, the Blob’s (only) cell contains millions of nuclei, which are all constantly dividing at the same time. The organism is usually found on forest floors in Europe and ‘likes’ temperatures between 19- and 25-degree Celsius. For the sake of our viewing pleasure (and consequential nightmares), scientists grew the Paris-based organism in Petri dishes, fed it oatmeal, waited for it to grow, grafted it onto a tree bark (which the mold also feeds on), and then placed the bark on a terrarium in the zoo — and called it “The Blob.”

According to a 2010 study published in the Journal of Plant Research, the organism has 720 sexes or unique mating types, determined by a range of different genes that come in multiple variants. It reproduces by releasing spores that develop into sex cells; when any two sex cells containing different variants of those 700+ sex genes meet, it is said to have reproduced. (So much for gender being a ‘natural’ binary. Pssh!) That’s about all we know, as far the Blob’s nature goes.

Oh, and it kind of just creeps on whatever you put in its way, with a speed of up to four centimeters per hour — without legs, wings or arms.

We know a LITTLE about what the Blob can do

We know the Blob eats. It’s diet consists of fungal spores, bacteria, and other microbes, but its guilty pleasure is — oats. But how, without a mouth or digestive system? The Blob, and other polycephalum, slime onto food by creating networks of tubes through which nutrients are absorbed and transported throughout the only cell in the Blob, giving the multiple nuclei the nutrition they need to keep functioning.

Related on The Swaddle:

Milky Way’s Supermassive Black Hole Has Suddenly Started Swallowing More of the Galaxy

We know the Blob thinks and has memory, despite literally being one giant brainless cell. In a 2016 study published by the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B., it was found the Blob can learn to avoid substances and environments that irritate it, like caffeine and bright light, and then remember that behavior up to a year later. This information can also be passed between its parts, without the organism having any of the biological components normally required for memories to form — neurons, a brain, a nervous system … nothing.

But, we know the Blob can solve problems. In a 2016 study published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, researchers found that the Blob could solve a specially adapted version of the ‘two-armed bandit’ problem, which examines decision-making abilities. This test isn’t normally administered to an organism without a brain, but the brainless Blob was able to investigate two food options, identify the more nutritious one, and then harvest it. This was the first time a brainless organism solved the two-armed bandit problem.

And it’s not just these specifically designed problems. The Blob is intelligent enough to solve math problems too. Slime molds like the Blob are often used to solve the Traveling Salesman Problem, a complex problem used to test algorithms. It’s a classic route optimization puzzle that asks the computer to figure out the shortest route between a list of cities, one that crosses each city once. When researchers from Japan gave the problem to a slime mold, they found that even when the number of cities increased, the time the slime took to figure out a solution didn’t increase that much. Scientists think this ability of slime molds — to figure out new solutions really quickly — can be used to make faster computers in the future.

“The blob is a living being which belongs to one of nature’s mysteries,” Bruno David, director of the Paris Museum of Natural History, of which the Zoological Park is part, said to The Guardian. “It surprises us because it has no brain but is able to learn … and if you merge two blobs, the one that has learned will transmit its knowledge to the other.”

There’s more to suggest the Blob is intelligent, according to a 2010 study published in the journal Science. When researchers presented slime mold like the Blob with oat flakes arranged in the pattern of Japanese cities around Tokyo, the brainless, single-celled organism not only demonstrated its ability to figure out a way out of a maze, it constructed a network of tubes around the pattern — a network that looked eerily similar to the layout of the Japanese rail system. (Why did so many Japanese engineers spend so much time and money making an intricate, well-designed rail system when they could have just asked the Blob?)

In another 2008 study published in Physical Review Letters, a team of researchers found that a slime mold can actually anticipate when an event will occur and prepare itself for it. When they exposed the Blob to consecutive pulses of electricity, the organism started slowing its speed right before the next pulse was about to hit. Scientists are still divided over whether this counts as the organism learning or merely represents reflex — but does it really matter? The point is, if we ever reach a situation where we have to launch an offense against the Blob, it’ll KNOW.

And, as if all this isn’t surreal enough, the organism can heal itself in minutes if cut in half. The Paris Blob, for instance, is already 10 meters long and, according to French news website, The Local, scientists have discovered that it is very hard to kill: it can survive being put in the microwave — and can heal itself in under two minutes when split. Like Wolverine, but smarter.

To cut a long story short, this is the way the world ends. Not with a bang, but a Blob. It’s aptly named after the 1958 cult horror film The Blob, in which an alien life form devours all of Pennsylvania, because let’s be honest, how are we ever going to neutralize a self-healing, thinking, intelligent-but-brainless organism that can solve complex algorithms, feed itself, silently move around and grow over everything, and fuse back together if (violently, repeatedly) split — should it choose to reduce all humans into goop?

Scientists believe slime mold is not dangerous, but they also said the Large Hadron Collider is going to explode and end the world, so I’m choosing to err on the side of caution with the Blob till they know more, thanks very much. Either that, or I date it, because … hundreds of sexes AND good at math? Yum.

Pallavi Prasad is The Swaddle's Features Editor. When she isn't fighting for gender justice and being righteous, you can find her dabbling in street and sports photography, reading philosophy, drowning in green tea, and procrastinating on doing the dishes.

Related

From Production to Use, Infant Formula Is Bad for the Environment