Cancel Culture Is Canceled. Meet Accountability Culture.

The difference between accountability culture and cancel culture is the same as the one between retributive justice and restorative justice.

Cancel culture’s whole point was accountability. But it didn’t turn out that way.

Living in the digital age, “cancel culture” is a term most of us are familiar with, even if we don’t feel the same way about the phenomenon. In 2021, a Forbes article implied that cancel culture was nothing but “long overdue accountability for the privileged.” Indeed, cancel culture had begun as a tool for social change that enabled individuals from marginalized communities to seek accountability from people in positions of power and privilege. To that extent, cancel culture was empowering — with millions of strangers on the internet coming together to take back power from people abusing it, and forcing them to take responsibility for their actions.

But soon, in the era of performative wokeness and relentless virtue signaling, cancel culture evolved to make netizens on social media feel as though they were part of a Bigg Boss-esque setting — with inescapable monitoring devices recording every one of their ommissions and commissions, and the tiniest of slip-ups exposing them to the risk of being eliminated a.k.a. “being canceled.” In doing so, though, cancel culture is, in practice, inching dangerously close to the territory of cyber-bullying — “a modern form of ostracism,” as one publication called it.

“[W]hen a group of people cancels a famous individual whose faults are thin, and whose behavior is repentant — cancel culture teeters and shows its flaws… It’s time we stop using cancel culture to immediately write off anyone who makes a mildly problematic mistake,” Aditi Murti had written in The Swaddle, explaining how the overuse of cancel culture eclipses the objective of seeking accountability. “Every single person who joined the Internet at a young age has left behind a legacy of unsavory content. While some have changed their opinions over time, others haven’t, and most don’t go back to carefully comb through their posts to delete material that deems them cancel-worthy… [Yet] we forget that canceling young people who misspoke the same way as we cancel unrepentant predators effectively closes the channel of communication, often even pushing young people away from progressive causes.”

In essence, rather than promoting accountability, cancel culture has come to “promot[e] ostracization over education, condemnation over compassion, and is deaf to redemption and change,” Pamela Rutledge, a media psychologist, wrote in Psychology Today.

Besides, the term cancel culture began to be widely derided and mocked by conservatives who cried ‘cancel culture’ at the smallest instances of the public holding them accountable. In essence, by exaggerating its meaning, they successfully turned cancel culture into an eye-roll inducing way to avoid accountability.

Naturally, then, the first step toward salvaging what had begun as a powerful tool to influence change through social media, is to reinstate accountability into the process again — resulting in the entrance of “accountability culture” into our collective lexicon.

Related on The Swaddle:

Why Usage of Trigger Warnings Persist Despite Research Suggesting They Might Be Counterproductive

The largely black-and-white approach of cancel culture seeks to punish, censor, and exclude, rather than encourage personal growth and learning — denying individuals the chance to amend their perspectives and behavior. On the contrary, the accountability culture acknowledges that, as human beings, we do make mistakes, but can also learn from them and rectify our ways, if given the opportunity to do so. It doesn’t absolve people of the harm they cause unto others — particularly toward marginalized communities, though. Instead, it endeavors to hold them accountable and demand change.

To a great extent, then, the accountability culture critiques unjust systems and unfair structures, whereas cancel culture — in its present form, at least — is devolving into a device that demonizes individuals.

In the era of trials by social media, in a sense, the difference between accountability culture and its predecessor is the same as the one between restorative justice and retributive justice. The former focuses on fixing the harm done by the perpetrator, making them aware of its consequences, and finally, integrating them into society by enabling them to be better individuals. The latter, much like cancel culture, is too fixated on the idea of punishment to effect any actual change.

Reintroducing accountability as an integral element in the digital justice landscape can curb the perverse use of cancel culture to accumulate woke points for social gain. “[Cancel culture] gained political overtones as name-calling and labeling became embedded in social discourse, sometimes from the very people we should be able to look up to. The banner of ‘canceling’ provides a smokescreen that distracts us from fundamental moral issues by embroiling us in an emotionally charged event,” writes Rutledge. “It preys on people’s tendency to jump on the bandwagon and join in an activity because others are doing it, not because of evidence. Participation is motivated as much by fear of missing out or fear of being targeted for not supporting the cause.”

By threatening social exclusion, then, cancel culture — if misused — can become a dangerous weapon to control social discourse by silencing dissenting voices, especially those that challenge the dominant narrative. In doing so, it doing so, it exposes society to the risk of creating a climate of fear, where individuals feel they cannot speak their minds for fear of being canceled.

Related on The Swaddle:

Why the Trend of ‘Trauma Dumping’ On Internet Strangers Needs to Go

“[T]he same tactics have also been used to scare people into submission and punish enemies, such as the Salem witch trials and the McCarthy-era Red Scare,” Rutledge adds. This isn’t to say that cancel culture itself is a bane in the digital era, or that every attempt at challenging its prominence is motivated by a vision of embracing diversity. If that were the case, the need for cancel culture wouldn’t have cropped up, perhaps. The problem, merely, is its misuse.

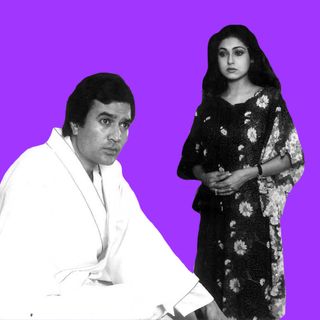

As we saw during the #MeToo movement, cancel culture can, at the end of the day, serve as a powerful tool for keeping individuals and institutions with a history of causing harm in check. But by gratuitously invoking its power, over and over again, we diluted its worth — hurting the cause of change it represented. This is reflected within the #MeToo movement itself, which eventually became “the real victim of cancel culture,” as one article described. Canceling individuals because doing so seemed to be in vogue is, perhaps, the reason why Louis C.K. recently won a Grammy, Woody Allen and Luv Ranjan are making movies again, Aziz Ansari is glorified for apologizing without taking responsibility for his sexual misconduct, and Tanmay Bhat is continuing with his brand of jokes, multiplying followers and spreading misinformation — all after being back from their brief exiles with nothing to show that they have, indeed, evolved as individuals.

As the Los Angeles Magazine remarked, “Cancel culture has been reduced to time-out for adults.” It’s time to bring accountability — in its true sense — into the picture again.

“[F]ar too often, people who call for accountability on social media seem to slide quickly into wanting to administer punishment instead. In some cases, this process really does play out with a mob mentality, one that seems bent on inflicting pain and hurt while allowing no room for growth and change, showing no mercy, and offering no real forgiveness — let alone allowing for the possibility that the mob itself might be entirely unjustified,” Aja Romano writes in Vox.

Accountability is about taking responsibility. Even as accountability culture rises to take over cancel culture, it becomes pertinent to ensure that it extends beyond performative woke-speak, and isn’t overused to the point where people start censoring themselves, fearing a backlash for nothing in particular. Its the democratization of the internet that birthed the digital iteration of cancel culture; now, as it is stifling that very democratization, it is important to hold cancel culture accountable.

Devrupa Rakshit is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She is a lawyer by education, a poet by accident, a painter by shaukh, and autistic by birth. You can find her on Instagram @devruparakshit.

Related

Woe Is Me! “My Situationship Ended Because I Wanted a Relationship. Why Do I Feel Guilty?”