Why Usage of Trigger Warnings Persist Despite Research Suggesting They Might Be Counterproductive

Using trigger warnings can be “invalidating” to trauma survivors because they’re told — over and over again — that the warnings are helping when, in reality, they aren’t.

“Trigger warnings” — or the rather synonymous “content warnings,” “distress warnings,” and “content notes” — have become a ubiquitous feature of social media in the present day and age. From content creators to news media to stage performers, almost everyone has used them — or, at least, felt the pressure to do so. Yet, netizens continue to be firmly divided on the value of the practice.

“[T]rigger warnings have become a flashpoint in the modern-day culture wars. Proponents are branded as overly sensitive snowflakes who do too much to keep their students safe. Opponents are caricatured as Quillette-reading inhabitants of the ‘intellectual dark web’ who want everyone to toughen up already,” Olga Khazan noted in The Atlantic in 2019. “But all this arguing has been taking place over an intervention that hasn’t been studied very thoroughly at all.”

Khazan is right. While the practice may be well-intentioned in its endeavor to alert audiences to potentially distressing content while signaling empathy to trauma survivors, its effectiveness remains largely under-researched and unproven.

Some research does suggest that trigger warnings may be able to reduce distress — but only very, very marginally. A 2018 paper, though, concluded that “trigger warnings” were not only largely ineffective but also, in some cases, amplified the anxiety people reported in response to distressing material. Another study from 2021 noted that trigger warnings can ultimately prolong the adverse impacts of recalling painful memories; perhaps, because they tell our brains to expect something negative and, in doing so, worsen the distress we feel.

Further, “trigger warnings are countertherapeutic because they encourage avoidance of reminders of trauma, and avoidance maintains PTSD,” says Richard McNally, co-author of the 2018 study and author of Remembering Trauma. “If you need a trigger warning, you need PTSD treatment… [and should consider] evidence-based, cognitive-behavioral therapies… involv[ing] gradual, systematic exposure to traumatic memories until their capacity to trigger distress diminishes.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Why the Trend of ‘Trauma Dumping’ On Internet Strangers Needs to Go

Payton Jones, who co-authored the study with McNally, also believes it can be “invalidating” to trauma survivors when they’re told — over and over again — that the warnings are helping when, in reality, they aren’t.

So, if trigger warnings largely do not serve trauma survivors, who do they benefit? Arguably, their pervasiveness and endurance in a realm of transient trends make it worth looking into why people continue to use them.

It’s safe to assume that most people use trigger warnings from a genuine place of concern towards the emotional angst trauma survivors often live with — in addition to the panic traumatic memories can induce in them. Kate Manne, for instance, an assistant professor of philosophy at Cornell University, believes in prefixing her lectures with trigger warnings. Explaining why, Manne wrote in The New York Times, “With appropriate warnings in place, vulnerable students may be able to employ effective anxiety management techniques, by meditating or taking prescribed medication… It’s not about coddling anyone. It’s about enabling everyone’s rational engagement.” She believes, otherwise, “for someone who has experienced major trauma, vivid reminders can serve to induce states of body and mind that are rationally eclipsing… [Being] flooded with anxiety to the point of struggling to draw breath, and feeling disoriented, dizzy and nauseated… [can make it] impossible to think straight.”

Moreover, we also live in a world where we constantly have more access to terrible news than at any other point in history. The crisis fatigue it engenders then, understandably, leaves people overwhelmed — inspiring them often to attempt to alleviate the experience for others. An easy way to do that is by offering people warnings before exposing them to disturbing content. Not everyone is prepared to read about a brutal lynching or a grievous assault on a Monday morning — or, perhaps, ever. And so, amid the overload of traumatic news that leads to a certain kind of helplessness, trigger warnings offer a way to regain an illusion of control in the world — or even assuage one’s guilt for subjecting others to traumatic content.

For many others, though, using trigger warnings could simply be a mindless replication of trends — rooted in either virtue signaling, or the fear of being “canceled.” “In this Bigg Boss-esque setting where our words are constantly being monitored, it seems as if the smallest of missteps will lead to an elimination a.k.a. ‘being canceled,’” as an article on The Swaddle noted. So, in an era where people are rewarded for being performatively woke — as long as the performativeness is camouflaged — it’s clear why trigger warnings have already become an intrinsic part of “woke”-social scripts.

Related on The Swaddle:

How Society Makes It Difficult for Women, Minorities to Set Emotional Boundaries

As Payton notes, though, “From a clinical lens, you should never do anything that doesn’t work, period, even if it doesn’t do harm. If it’s not actively helping, encouraging its use would essentially be engaging in clinical pseudoscience.”

However, despite the effectiveness of different forms of exposure therapy in treating PTSD, the fact remains that barriers to trauma-informed care — in addition to the unaffordability of therapy itself in countries like India — might pose practical challenges in following McNally’s advice to prevent “encourag[ing] avoidance of reminders of trauma” through trigger warnings.

And, of course, an argument can be made in favor of using content warnings to foster a culture of consent that extends even to the kind of content one engages with in this digital age. However, we continue to be at an impasse on balancing effective usage of warnings while ensuring trauma survivors are not counterproductively triggered in our endeavor to avoid precisely that.

Perhaps, the solution, here, lies not in looking at trigger warnings themselves but at what comes next. Research from earlier this year suggests that the reason “[trigger] warnings fail to ameliorate negative emotional reactions is that these warnings may not help people bring coping strategies to mind.”

Ultimately, a lot more research is required yet to determine how we proceed. And while we continue to look for ways to balance the scale, there’s one thing we do know: in this era of scripted responses and performative wokeness, the solution we come up with will catch on – even more reason to ensure that the solution we come up with is backed up by more research than “trigger warnings” ever were.

In the meantime, it is imperative that both proponents and opponents of using warnings recognize that the practice – albeit flawed and imperfect – is ultimately intended to hold space for vulnerable communities. And that is what we must not lose sight of as we imagine alternative ways of living.

Devrupa Rakshit is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She is a lawyer by education, a poet by accident, a painter by shaukh, and autistic by birth. You can find her on Instagram @devruparakshit.

Related

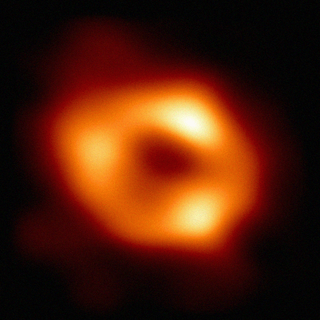

Scientists Found 830‑Million‑Year‑Old Organisms Potentially Alive in Crystals