Childbirth Can Permanently Alter Bones, Finds Study

The study points to the significant effects of reproduction on female bodies.

A team of anthropologists has discovered that giving birth permanently changes female bones in a way that was previously unknown. This fact emerged as a result of a study on primates — specifically macaques — revealing how reproduction can have long-term impacts on the female body. The findings could potentially inform our understanding of how events like childbirth are recorded in skeletal tissues of primates, including humans.

Their findings challenge the popularly-held belief that bones are “static”. Instead, the skeleton is constantly changing and responding to physiological processes, noted the study’s authors.

The effects of menopause on skeletal health have been widely studied, in both humans and non-human primates. In the case of humans, women rapidly lose bone mass during menopause, which increases the risk of osteoporosis and fractures. However, the impact of earlier reproductive events on bone composition have remained relatively unclear, the researchers noted in a press release. It was to bridge this knowledge gap that the team undertook this study, publishing their findings in the journal PLOS ONE.

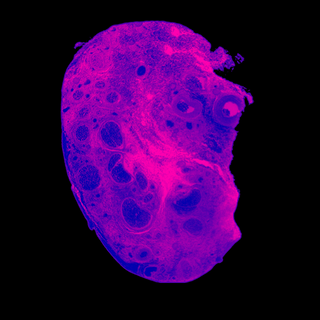

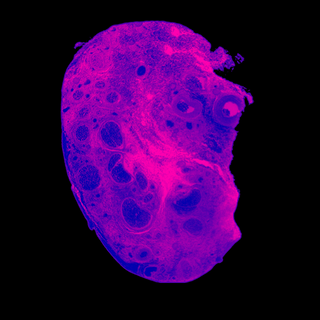

The researchers conducted an electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray analysis on the bones of macaques that revealed concentrations of calcium and phosphorus were lower in bones that formed during reproductive events, when compared to the bones of females who had not given birth. A change was also noticed in magnesium concentration, which declined in females who were breastfeeding.

“Our findings provide additional evidence of the profound impact that reproduction has on the female organism, further demonstrating that the skeleton is not a static organ, but a dynamic one that changes with life events,” said Paola Cerrito, who led the research. Cerrito and team examined the growth rate of the lamellar bone – the main bone type in mature skeletons – in thigh bones of both female and male macaques who died of natural causes. They analyzed the chemical composition of tissue samples, comparing changes in concentrations of minerals and nutrients between bones of females who had given birth and those belonging to males or females who had not reproduced.

Related on The Swaddle:

Postpartum Depression Can Hit Any Time Within 3 Years of Childbirth: Study

This ties in with previous research that suggests women lose calcium during pregnancy as their bodies adapt to meet the nutritional demands of a growing fetus. A study published last year noted that during pregnancy, calcium absorption from the intestine increases, and is transported to the fetus via the placenta. If the mother’s calcium intake is low, this could result in low bone mineral density while also affecting bone maturation and mineral density in the newborn.

Moreover, women lose around 3-5% of their bone mass during breastfeeding too, though this can be recovered post weaning. During lactation, the mother’s bones are “resorbed” to ensure the milk is rich in calcium. While bone density is said to improve post-pregnancy, there have been rare instances of pregnancy or lactation-associated osteoporosis – where the loss of calcium results in fragile bones, especially in the vertebrae.

The team, however, emphasized that their research does not address what such changes in skeletal composition might mean for either primate or human health. In fact, the long-term effects of reproduction on women’s bodies and health go far beyond skeletal changes, but remain relatively understudied. This becomes especially stark in the case of postpartum care, which has long focused on the newborn and sidelined women’s physical and mental health needs.

The wide array of women’s experiences point to a need for greater research on maternal health care that could increase awareness of how childbirth affects female bodies. The latest study serves to highlight one aspect of this in macaques. “Our research shows that even before the cessation of fertility the skeleton responds dynamically to changes in reproductive status… Moreover, these findings reaffirm the significant impact giving birth has on a female organism—quite simply, evidence of reproduction is ‘written in the bones’ for life,” Cerrito said.

Ananya Singh is a Senior Staff Writer at TheSwaddle. She has previously worked as a journalist, researcher and copy editor. Her work explores the intersection of environment, gender and health, with a focus on social and climate justice.

Related

How Social Media Perpetuates Toxic Diet Culture