Covid19 Social Media Groups Are Saving Lives. But For People Without Internet, the Situation Is Grim

People who can’t access virtual communities are bearing the most severe impact of the second wave.

The internet rarely agrees upon anything, but this time the consensus is loud and clear: social media platforms are functioning as proxies to the healthcare system in providing resources to Covid19 patients. Under the shadow of a worsening second coronavirus wave, the emergency SOS calls and texts looking for oxygen cylinders, hospital beds, medicine supplies, and Covid tests are becoming frequent and urgent.

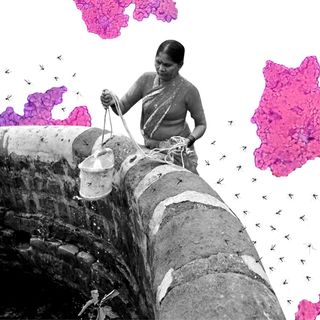

But while social media networks — WhatsApp, Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook — become digital helplines, it is also an important reminder that people without access to the internet and the communities there remain excluded from the novel and effective support systems.

Almost half of the world’s population has no access to the internet — in rural India, only 34% of women and 55% of men have ever used the internet. Overall, only 14.4% of rural households have internet facilities, and even fewer — 4.4% of households — have a computer. Rural women are also least likely to have internet access, signaling a significant digital divide in the country, according to India’s fifth National Family Health Survey (NFHS).

“Connectivity still remains a largely urban phenomenon in India. It will take a long time to bridge the difference,” Pavan Duggal, a cybersecurity expert, told DW. This gap, or digital divide, prevents them from reaching out to urban virtual communities for help and lengthens the time it takes information and other help to reach them. People on the other side of the digital divide struggle to lay their hands on basic resources, strengthening the longstanding argument that internet connectivity should be a fundamental right.

While rural connectivity continues to lag, people in tier 2 and tier 3 cities, who may have access to Twitter or other platforms but struggle to get their posts in the mainstream dialogue, also face a similar disconnect. For them, the only viable option remains to laboriously call government helplines and numbers — many of which are reportedly not picking up or have long waiting times.

The lack of support to the vulnerable communities gets concerning in light of several media reports noting the mishandling of the Covid19 crisis by states: various states are reportedly fudging data, not recording Covid19 deaths, and failing to take Covid tests to maintain positive numbers. Pictures and videos of crematorium grounds overwhelmed with dead bodies from states like Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Gujarat reveal a different picture.

A UP-based journalist Vinay Kumar Srivastava died while waiting for a hospital bed last week. “At Balrampur Hospital, the security guards even abused me. ‘Go away. Get a letter from the CMO first. Only Covid-positive patients can be admitted. There are no beds’,” his son recalled in a conversation with The Print.

One can only wonder if social media appeals for help are only representing the struggles of a select few, how worse is the situation for those who are distant — both technologically and geographically.

Related on The Swaddle:

The Coronavirus Pandemic Holds a Mirror to Our Culture’s Shameless Classism

The realization is grim, but doesn’t take away from the utility online communities are providing at this time of the pandemic. The second Covid19 wave has led to a collapse of the healthcare system: people are dying waiting in lobbies or outside hospital gates, beds and oxygen are running out, Covid19 medicine supplies continue to be in short supply. On Facebook, there were 27,000 posts on Remedesivir on Sunday, according to a Times of India report. On Instagram and Twitter, urgent calls of finding vacant ICU beds or vials of oxygen are quickly populating the social media stream; groups are flooded with requests for plasma donors. People are also creating Google Docs, Instagram Reads, and other resource buckets to compile city-specific information about Remdesivir suppliers, available hospital beds, and blood donors. Anything and everything to help someone in need.

These are fervent pleas for help, responded to by eager and kind citizens to help wherever they can: people are volunteering to pick up and deliver groceries for those in need, organizing themselves into volunteer groups. Some are just offering solidarity or expressing their grief with personal stories of loss and survival. Conversations online carry solemn news of sickness and mourning, but these action groups offer a sliver of hope in capturing the best of humanity.

The social, not just public health, events of the past year has set us up for tapping into our social networks. Community groups organized themselves around the Citizenship Act protests, the aftermath of the 2020 Delhi riots, the migrant workers’ crisis, and the farmers’ protests. A network of people coming together to offer services, share resources and lists, and offer support has proven useful in all political and social contexts. These communities and action groups emerged swiftly over the last few weeks; indubitably, it takes a lot the strength to engage in resource-finding and aid work during a pandemic.

But while these groups rush to relieve the burden of the health system, it is critical to keep in mind the thousands of people whose voices are drowning out amid chaos on Ground Zero. These communities are a reminder of how no system — internet and health included — is set up to serve disadvantaged groups. Despite being one year into the pandemic, the system remains unprepared and deficient to meet the needs of the people.

The most solemn realization, perhaps, the true extent of the Covid19 crisis will never be fully known.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Divert Oxygen From Industrial Use to Covid19 Patients, Govt Tells States