‘Delhi Crime’ Season 2 Shows the Injustices India’s ‘Criminal Tribes’ Face

The British criminalized entire communities by categorizing them as habitual criminals. This prejudice still shapes law and order.

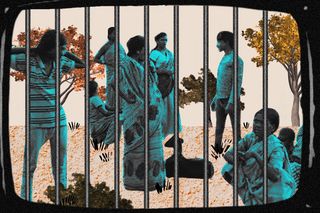

Picture this: you are presumed to have crime in your DNA by virtue of being born in a certain community. Whenever there is a major crime in the area, the cops might just lathicharge, handcuff nearly half of your village, and keep you in custody until the real criminals are apprehended.

If this sounds straight out of a medieval-era penal colony, you would be mistaken. The source of this violative approach is the 1871 Criminal Tribes Act promulgated by the British government, which in effect criminalized entire tribal communities across India by categorizing them as habitual criminals. Their movement was restricted too, making them prisoners in their own land.

The many injustices meted out to these “criminal” tribes as a result of this Act are the inspiration for the second season of the Emmy-winning Netflix show Delhi Crime. In it, we are reminded of the horrors faced by the Pardhi and Bawariya communities, who were unfairly targeted across North India for being part of the Kacha-Baniyan gang – a group of criminals who would undertake armed robberies, often resulting in brutal murders. They became infamous for allegedly committing these crimes while wearing only their undergarments, oiling their bodies so that they could slip away more easily.

This is also not the first time Indian media has explored the oppression faced by these tribes. In the 150th year of the Criminal Tribes Act, last year, the Surya-starrer Jai Bhim was released to widespread acclaim. The film was inspired by countless real-life incidents of the Irula tribe being unfairly targeted by the Tamil Nadu state police, from having fake cases of theft registered against them to being accused of enabling mass rapes.

According to Maya Ratnam, an anthropologist who has researched the dynamics of society and power in the forest-dwelling communities of central India, the factors that contributed to the British terming certain communities as “criminals” were multifaceted.

“To a certain extent, the British wanted to tame some of the hill tribes who lent support to the 1857 mutiny,” she says. “On the other hand, the advent of railway lines and new modes of trade and communication meant that these tribes no longer served their original nomadic purpose and were viewed as itinerant communities that needed ‘fixing’ by the British.”

The nomadic nature of such tribes posed a threat to the British as they feared getting looted by the “thugees” – gangs of professional robbers and murderers in British India.

Related on The Swaddle:

Tribal Community in Madhya Pradesh Evicted From Homes Without Official Notice

Post-independence, in August 1949, the Criminal Tribes Act was repealed on the recommendations of a committee set up by the erstwhile Government of Bombay, which included the then Chief Minister Morarji Desai. In effect, more than 2,300,000 tribals were decriminalized overnight. However, following the repeal, there was a massive public outcry, and people began blaming a perceived spike in violence on the “criminal” tribes – leading to the enactment of the Habitual Offenders Act (HOA) in 1952.

“They simply replaced the Criminal Tribes Act with the HOA,” says filmmaker, dramaturgist, and activist Dakxin Chhara, who belongs to the Chhara community that was initially listed as a criminal tribe. “The stigma of the state against the tribes is very much prevalent. We are the scapegoats, they can arrest and interrogate us anytime. In the eyes of the international community, I might be a National-Award-winning filmmaker, but for the Indian state, I will always be a criminal.”

He adds that the stigma of the cops against the denotified tribes begins right from police training academies, where they are taught about the ways of the criminal tribes and how they must be dealt with. This, he says, is the source of the prejudice of the cops against such tribes.

However, Neeraj Kumar, the former Commissioner of Delhi Police who led the investigation around the Kacha-Baniyan killings in the early 1990s tells The Swaddle that it was this academy training that helped him understand the behavioral patterns, rituals, traditions, and sociological conditions of Pardhis and the Bawariya communities responsible for the Kacha-Baniyan killings and robberies in the 1990s. He adds that cases of police excesses against tribes have in fact drastically reduced in the present day.

“One section of the cops don’t know about the denotified tribes and the other section of the force that is aware of them, ends up tarring all of them with the same brush,” he says. “There is no such thing as a “born criminal,” a person becomes a criminal because of their upbringing, the milieu they grow up in, or the training. A pathological criminal could belong from any section of the society.”

He also believes that the days of cops randomly arresting denotified tribes are long gone, but “if it is happening, then it’s deplorable and reprehensible.”

However, regardless of whether Kumar is right about the frequency of these encounters having reduced, constitutional guarantees for such tribes are either non-existent or remain a dead letter in law. A National Commission for Denotified, Nomadic and Semi-Nomadic Tribes (NCDNT), constituted in 2006, noted that “it is an irony that these tribes somehow escaped the attention of our Constitution makers and thus got deprived of the Constitutional support unlike Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.”

At present, according to a Parliamentary Standing Committee report, 269 denotified tribes are not covered under any reservation category and do not have any special constitutional guarantees. The 2017 Idate Commission report noted that nothing had changed in a decade – with most DNT communities still being deeply impoverished and 98% of them being landless.

There is an inherent dichotomy in the state’s approach towards such tribes – it simultaneously wants them to be “civilized” and remains absent when it comes to concrete affirmative action and constitutional guarantees. Anthropologist Ratnam says that this is a contradiction not just limited to criminal tribes but even with other “non-criminal tribes,” who are made to feel ashamed of their “primitive” rituals and traditions.

“All the committees post-Independence have really failed in the task to define and enumerate these communities and assess their diverse needs,” she says. “In effect, these communities have been failed by the promise of inclusion in the modern constitution.”

Arman Khan is a freelance writer and journalist based in Mumbai. He writes on the intersection of gender, lifestyle, and art.

Related

Woe Is Me! “I Get Jealous When My Friends Hang Out With Others. Will I End Up Friendless?”